Shikantaza is to practice or actualize emptiness. Although you can have a tentative understanding of it through your thinking, you should understand emptiness through your experience. You have an idea of emptiness and an idea of being, and you think that being and emptiness are opposites. But in Buddhism both of these are ideas of being. The emptiness we mean is not like the idea you may have. You cannot reach a full understanding of emptiness with your thinking mind or with your feeling. That is why we practice zazen.

When you see a plum blossom, or hear the sound of a small stone hitting bamboo, that is a letter from the world of emptiness.

We have a term, shosoku, which is about the feeling you have when you receive a letter from home. Even without an actual picture, you know something about your home, what people are doing there, or which flowers are blooming. That is shosoku. Although we have no actual written communications from the world of emptiness, we have some hints or suggestions about what is going on in that world—and that is, you might say, enlightenment. When you see a plum blossom, or hear the sound of a small stone hitting bamboo, that is a letter from the world of emptiness.

Besides the world which we can describe, there is another kind of world. All descriptions of reality are limited expressions of the world of emptiness. Yet we attach to the descriptions and think they are reality. That is a mistake because what is described is not the actual reality, and when you think it is reality, your own idea is involved. That is an idea of self.

Many Buddhists have made this mistake. That is why they were attached to written scriptures or Buddha’s words. They thought that his words were the most valuable thing, and that the way to preserve the teaching was to remember what Buddha said. But what Buddha said was just a letter from the world of emptiness, just a suggestion or some help from him. If someone else reads it, it may not make sense. That is the nature of Buddha’s words. To understand Buddha’s words, we cannot rely on our usual thinking mind. If you want to read a letter from the Buddha’s world, it is necessary to understand Buddha’s world.

“To empty” water from a cup does not mean to drink it up. “To empty” means to have direct, pure experience without relying on the form or color of being. So our experience is “empty” of our preconceived ideas, our idea of being, our idea of big or small, round or square. Round or square, big or small don’t belong to reality, but are simply ideas. That is to “empty” water. We have no idea of water even though we see it.

When we analyze our experience, we have ideas of time or space, big or small, heavy or light. A scale of some kind is necessary, and with various scales in our mind, we experience things. Still the thing itself has no scale. That is something we add to reality. Because we always use a scale and depend on it so much, we think the scale really exists. But it doesn’t exist. If it did, it would exist with things. Using a scale you can analyze one reality into entities, big and small, but as soon as we conceptualize something it is already a dead experience.

To empty is not the same as to deny. Usually when we deny something, we want to replace it with something else.

We “empty” ideas of big or small, good or bad from our experience, because the measurement that we use is usually based on the self. When we say good or bad, the scale is yourself. That scale is not always the same. Each person has a scale that is different. So I don’t say that the scale is always wrong, but we are liable to use our selfish scale when we analyze, or when we have an idea about something. That selfish part should be empty. How we empty that part is to practice zazen and become more accustomed to accepting things as it is without any idea of big or small, good or bad.

For artists or writers to express their direct experience, they may paint or write. But if their experience is very strong and pure, they may give up trying to describe it: “Oh my.” That is all. I like making a miniature garden around my house, but if I go to the stream and see the wonderful rocks and water running, I give up: “Oh, no, I shall never try to make a rock garden. It is much better to clean up Tassajara Creek, picking up any paper or fallen branches.”

In nature itself there is beauty that is beyond beauty. When you see a part of it, you may think this rock should be moved one way, and that rock should be moved another way, and then it will be a complete garden. Because you limit the actual reality using the scale of your small self, there is either a good garden or a bad garden, and you want to change some stones. But if you see the thing itself as it is with a wider mind, there is no need to do anything.

The thing itself is emptiness, but because you add something to it, you spoil the actual reality. So if we don’t spoil things, that is to empty things. When you sit in shikantaza, don’t be disturbed by sounds, don’t operate your thinking mind. This means not to rely on any sense organ or the thinking mind and just receive the letter from the world of emptiness. That is shikantaza.

To empty is not the same as to deny. Usually when we deny something, we want to replace it with something else. When I deny the blue cup, it means I want the white cup. When you argue and deny someone else’s opinion, you are forcing your own opinion on another. That is what we usually do. But our way is not like that. By emptying the added element of our self-centered ideas, we purify our observation of things. When we see and accept things as they are, we have no need to replace one thing with another. That is what we mean by “to empty” things.

If we empty things, letting them be as it is, then things will work. Originally things are related and things are one, and as one being it will extend itself. To let it extend itself, we empty things. When we have this kind of attitude, then without any idea of religion we have religion. When this attitude is missing in our religious practice, it will naturally become like opium. To purify our experience and to observe things as it is is to understand the world of emptiness and to understand why Buddha left so many teachings.

In our practice of shikantaza we do not seek for anything, because when we seek for something, an idea of self is involved. Then we try to achieve something to further the idea of self. That is what you are doing when you make some effort, but our effort is to get rid of self-centered activity. That is how we purify our experience.

For instance, if you are reading, your wife or husband may say, “Would you like to have a cup of tea?” “Oh, I am busy,” you may say, “don’t bother me.” When you are reading in that way, I think you should be careful. You should be ready to say, “Yes, that would be wonderful, please bring me a cup of tea.” Then you stop reading and have a cup of tea. After having a cup of tea, you continue your reading.

Our effort is to get rid of self-centered activity. That is how we purify our experience.

Otherwise your attitude is, “I am very busy right now!” That is not so good, because then your mind is not actually in full function. A part of your mind is working hard, but the other part may not be working so hard. You may be losing your balance in your activity. If it is reading, it may be okay, but if you are making calligraphy and your mind is not in a state of emptiness, your work will tell you, “I am not in a state of emptiness.” So you should stop.

If you are a Zen student you should be ashamed of making such calligraphy. To make calligraphy is to practice zazen. So when you are working on calligraphy, if someone says, “Please have a cup of tea,” and you answer, “No, I am making calligraphy!” then your calligraphy will say, “No, no!” You cannot fool yourself.

I want you to understand what we are doing here at Zen Center. Sometimes it may be all right to practice zazen as a kind of exercise or training, to make your practice stronger or to make your breathing smooth and natural. That is perhaps included in practice, but when we say shikantaza, that is not what we mean. When we receive a letter from the world of emptiness, then the practice of shikantaza is working.

Thank you very much.

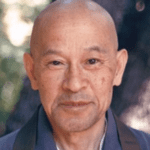

This talk was published in the Spring 2002 issue of Lion’s Roar. It is from Not Always So, a collection of Suzuki Roshi’s teachings edited by Edward Brown and published by HarperCollins. © 2003 by Shunryu Suzuki. All rights reserved.