In this excerpt from Bhante Gunaratana’s book Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English, the great Theravada teacher explains why all practitioners should meditate on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, at every stage on the Buddhist path.

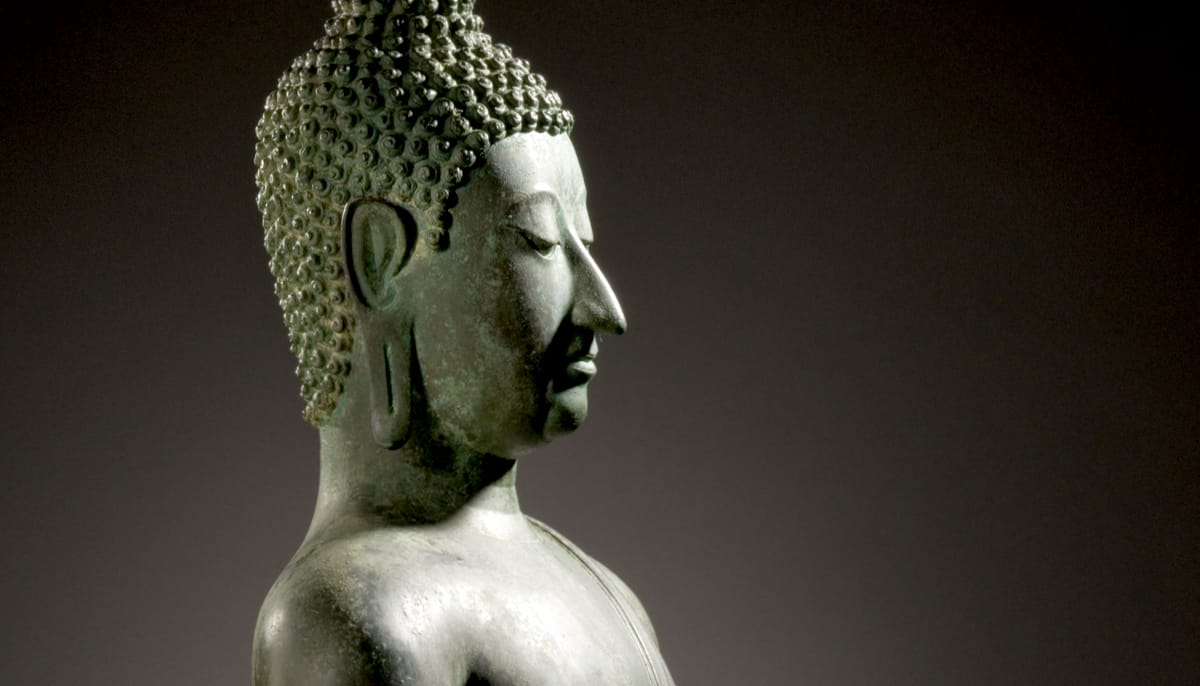

Mindfulness practice has deep roots in Buddhist tradition. More than 2,600 years ago, the Buddha exhorted his senior bhikkhus, monks with the responsibility of passing his teachings on to others, to train their students in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness.

“What four?” he was asked.

“Come, friends,” the Buddha answered. “Dwell contemplating the body in the body, ardent, clearly comprehending, unified, with concentrated one-pointed mind, in order to know the body as it really is. Dwell contemplating feeling in feelings… in order to know feelings as they really are. Dwell contemplating mind in mind… in order to know mind as it really is. Dwell contemplating dhamma in dhammas… in order to know dhammas as they really are.”

The practice of contemplating (or as we might say, meditating on) the Four Foundations—mindfulness of the body, feelings, mind, and dhammas (or phenomena)—is recommended for people at every stage of the spiritual path. As the Buddha goes on to explain, everyone—trainees who have recently become interested in the Buddhist path, monks and nuns, and even arahants, advanced meditators who have already reached the goal of liberation from suffering, “should be exhorted, settled, and established in the development of these Four Foundations of Mindfulness.”

We can assume that the word “bhikkhu” is used to mean anyone seriously interested in meditation. In that sense, we are all bhikkhus.

In this sutta, the Buddha is primarily addressing the community of bhikkhus, monks and nuns who have dedicated their lives to spiritual practice. Given this, you might wonder whether people with families and jobs and busy Western lives can benefit from mindfulness practice. If the Buddha’s words were meant only for monastics, he would have given this talk in a monastery. But he spoke in a village filled with shopkeepers, farmers, and other ordinary folk. Since mindfulness can help men and women from all walks of life relieve suffering, we can assume that the word “bhikkhu” is used to mean anyone seriously interested in meditation. In that sense, we are all bhikkhus.

Let’s look briefly at each of the four foundations of mindfulness as a preview of things to come.

Mindfulness of Body

By asking us to practice mindfulness of the body, the Buddha is reminding us to see “the body in the body.” By these words he means that we should recognize that the body is not a solid unified thing, but rather a collection of parts. The nails, teeth, skin, bones, heart, lungs, and all other parts—each is actually a small “body” that is located in the larger entity that we call “the body.” Traditionally, the human body is divided into thirty-two parts, and we train ourselves to be mindful of each. Trying to be mindful of the entire body is like trying to grab a heap of oranges. If we grab the whole heap at once, perhaps we will end up with nothing!

Moreover, remembering that the body is composed of many parts helps us to see “the body as body”—not as my body or as myself, but simply as a physical form like all other physical forms. Like all forms, the body comes into being, remains present for a time, and then passes away. Since it experiences injury, illness, and death, the body is unsatisfactory as a source of lasting happiness. Since it is not myself, the body can also be called “selfless.” When mindfulness helps us to recognize that the body is impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless, in the Buddha’s words, we “know the body as it really is.”

Mindfulness of Feelings

Similarly, by asking us to practice mindfulness of feelings, the Buddha is telling us to contemplate “the feeling in the feelings.” These words remind us that, like the body, feelings can be subdivided. Traditionally, there are only three types—pleasant feelings, unpleasant feelings, and neutral feelings. Each type is one “feeling” in the mental awareness that we call “feelings.” At any given moment we are able to notice only one type. When a pleasant feeling is present, neither a painful feeling nor a neutral feeling is present. The same is true of an unpleasant or neutral feeling.

The mind alone cannot exist, only particular states of mind that appear depending on external or internal conditions. Paying attention to the way each thought arises, remains present, and passes away, we learn to stop the runaway train.

We regard feelings in this way to help us develop a simple nonjudgmental awareness of what we are experiencing—seeing a particular feeling as one of many feelings, rather than as my feeling or as part of me. As we watch each emotion or sensation as it arises, remains present, and passes away, we observe that any feeling is impermanent. Since a pleasant feeling does not last and an unpleasant feeling is often painful, we understand that feelings are unsatisfactory. Seeing a feeling as an emotion or sensation rather than as my feeling, we come to know that feelings are selfless. Recognizing these truths, we “know feelings as they really are.”

Mindfulness of Mind

The same process applies to mindfulness of mind. Although we talk about “the mind” as if it were a single thing, actually, mind or consciousness is a succession of particular instances of “mind in mind.” As mindfulness practice teaches us, consciousness arises from moment to moment on the basis of information coming to us from the senses—what we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch—and from internal mental states, such as memories, imaginings, and daydreams. When we look at the mind, we are not looking at mere consciousness. The mind alone cannot exist, only particular states of mind that appear depending on external or internal conditions. Paying attention to the way each thought arises, remains present, and passes away, we learn to stop the runaway train of one unsatisfactory thought leading to another and another and another. We gain a bit of detachment and understand that we are not our thoughts. In the end, we come to know “mind as it really is.”

Mindfulness of Dhammas

By telling us to practice mindfulness of dhammas, or phenomena, the Buddha is not simply saying that we should be mindful of his teachings, though that is one meaning of the word “dhamma.” He is also reminding us that the dhamma that we contemplate is within us. The history of the world is full of truth seekers. The Buddha was one of them. Almost all sought the truth outside themselves. Before he attained enlightenment, the Buddha also searched outside of himself. He was looking for his maker, the cause of his existence, who he called the “builder of this house.” But he never found what he was looking for. Instead, he discovered that he himself was subject to birth, growth, decay, death, sickness, sorrow, lamentation, and defilement. When he looked outside himself, he saw that everyone else was suffering from these same problems. This recognition helped him to see that no one outside himself could free him from his suffering. So he began to search within. This inner seeking is known as “come and see.” Only when he began to search inside did he find the answer. Then he said:

Many a birth I wandered in samsara,

Seeking but not finding the builder of this house.

Sorrowful is it to be born again and again.

Oh! House builder thou art seen.

Thou shall not build house again.

All thy rafters are broken.

Thy ridgepole is shattered.

The mind has attained the unconditioned.

Reproduced from The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English with permission of Wisdom Publications.