Maps

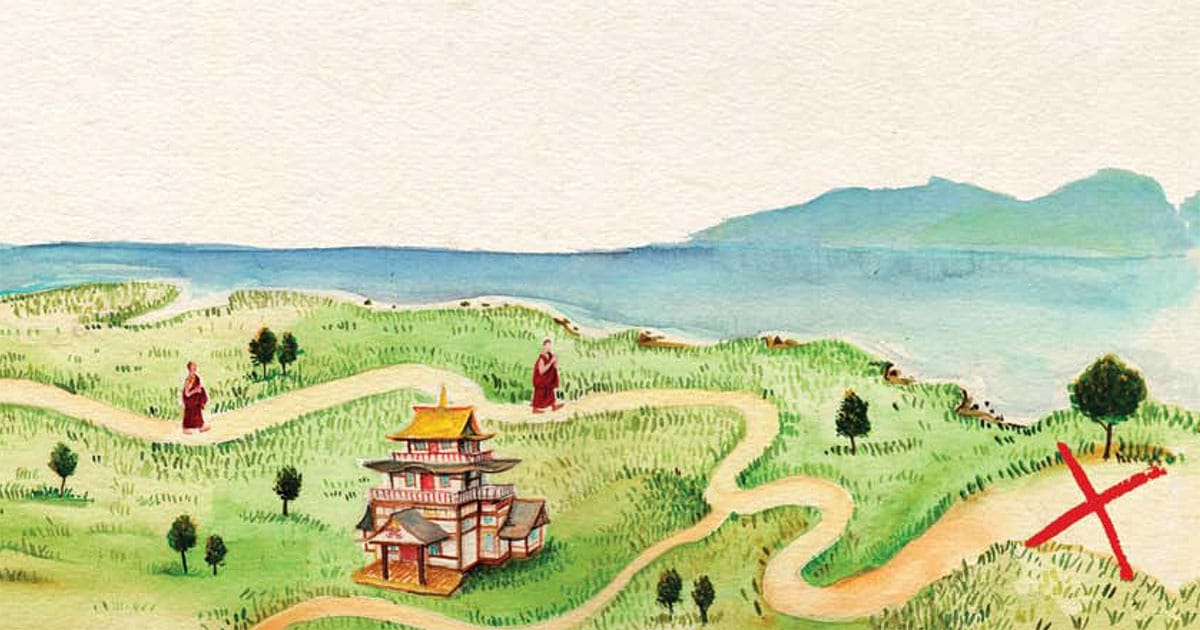

I have always been fascinated by maps. In grade school, when we were introduced to map reading and map making, it seemed so magical that the world and its complexity could be represented by pictures and diagrams on a simple sheet of paper. It was amazing that if you followed the directions on the map you would actually be able to get somewhere, even if you had never been there before. It got even better when I discovered that I could send off a cereal-box coupon and receive in the mail a genuine pirate’s map leading to a chest of buried treasure. These sepia maps, ancient looking and burned on the edges, led me to believe that I could follow such a map to the point where “X marks the spot.”

There are many kinds of maps. We create internal maps without even being aware of doing so, mapping our physical, emotional, and mental realities. By means of a map, you can find your way back to where you started without getting lost. A map can lead you to someplace new or give your friends a way to find you. Maps give us directions on how to proceed. They provide a feeling of security and are a defense against bewilderment and disorientation. It is a relief to be able to look at a map and see where you are. It is a relief to know that you are somewhere specific, that you came from somewhere and that there is somewhere to go.

Journeys

Journeys are challenging. We leave our familiar home and enter new territory. How do we know what to do and where to go? Embarking on a spiritual journey is like this. The new spiritual terrain can seem to be a kind of terra incognita, scary and possibly overrun by monsters. We are afraid we might get lost and not be able to find our way forward or back. We are on a treasure hunt, but we don’t know where to look. If we have the right map, we might be able to find that buried treasure, even if it has been underground for many years.

On the spiritual journey, it is possible to get stuck and not really go anywhere. It is also possible to be swept along so rapidly that we lose our bearings. If we have no map, we might drift about aimlessly and go round in circles. But if our trip is overly scripted, there will be no room for personal discoveries. It would be like signing up for a package tour in which every point of interest has been spelled out in advance. So we need the right kind of map, one that gives us a sense of direction and an overview of where we are going but also leaves room for us to explore. Along with a general map of the territory, we need a good guide for our journey who can point the way. This guide should have explored the region so thoroughly that he or she no longer needs an external map. Their familiarity with the terrain is so thorough that they have developed a kind of internal map, like an inner instinctual compass. But although they no longer need a map themselves, such guides recognize the value of maps for newcomers, as well as the limitations of relying on maps.

On my own journey, I have been fortunate to encounter both a guide and a map. In my case, the guide is the late Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the terrain is Vajrayana Buddhism, and the map is the teachings on the stages of the path.

Vehicles

In the Vajrayana tradition, one’s journey can be described in terms of three main vehicles, or yanas. The first is the path of individual liberation, the second is the Mahayana path of greater openness and compassion, and the third is the Vajrayana path of indestructible wakefulness. Each yana has its own integrity and completeness, and at the same time they form a unified system. Although any one of the three can be studied and practiced separately, the path of individual liberation, Mahayana, and Vajrayana are in fact expressions of a single path.

The dynamic nature of this model is exemplified by the use of the term yana, vehicle, rather than more static terms such as steps or stages. When you get into a vehicle, you definitely expect it to move along and carry you forward. Likewise, in the three-yana journey you are continually moving forward. There is an organic quality to the three-yana progression, in the sense that with a little care each experience on the spiritual path naturally evolves and grows. At the same time, as you progress along the path, you do not drop the previous yana as you move on to the next one.

Vajrayana teachers also liken the three yanas to building a house. Here, the yana of individual liberation provides the foundation, the connection with the Earth. There is no way to build a solid house with- out a foundation—it is what you build first, and it is the ballast or support for the whole structure. But a foundation alone is not a house; you need walls and windows and doors. This is like the Mahayana, for it provides the possibility of hospitality and a means of communication and exchange with the world. And finally, of course, you need a roof. You need shelter and protection and the kind of adornment that brings the whole picture together. That roof is the Vajrayana.

This straightforward and systematic guide for practitioners is a great benefit of the Tibetan tradition. The set of teachings by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, titled The Profound Treasury of the Ocean of Dharma, presents the three-yana teachings as the framework for deepening and refining the study and practice of the dharma. Trungpa Rinpoche placed great emphasis on these teachings and presented them in many individual talks and in public seminars. He came back to this topic again and again, and most notably, he used the three yanas as the structure for every one of the three-month-long Vajradhatu Seminaries he led for his most senior students. The Profound Treasury presents these teachings to the public for the first time.

The Yana of Individual Liberation

Before you can figure out the map of dharma, you first have to know where you are. The yana of individual liberation is like the spot on the map that says “You are here.” It is where you begin. This is the yana that introduces the fundamental principles and practices of the Buddhist tradition. These key insights are the foundation of the Buddhist path altogether and the underpinning of the subsequent two yanas.

View

In the path of individual liberation, you examine your view of yourself, your actions, and the world around you. You contemplate the nature of your own identity and discover that your seemingly solid self is in fact not all that solid. You see that sensations and experiences arise and fall continually, but if you try to find what holds them all together, you come up empty-handed. And as your own solidity begins to be questionable, you also begin to have doubts about the so-called solid world outside. There is a softening of the pain of alienation and the split between I and other.

In this yana, you also look more deeply into your actions and habits and their consequences. You examine the attitudes and actions that have brought you up to this point and take a hard look at where they will inevitably lead you in the future. You gain respect for how small actions can have big effects. By looking closely into these patterns, you can distinguish where and why you are stuck and where and how there might be openings for change.

This is the yana of personal responsibility. You begin to see your own role in creating the thought habits and emotional tangles that entrap you. You realize how much of what seems to be out there or coming at you is your own projections bouncing back at you.

This yana has a quality of purity and no nonsense, which can be summed up by the Buddha’s teaching on the four noble truths: suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path to liberation. The reality of suffering, and the many subtle expressions of suffering underlying our ordinary experiences of pain and pleasure, is not that easy to understand or accept. It is like we are addicted to dysfunctional living, so we keep telling ourselves it can’t really be all that bad. But maybe it is that bad, and once we take an interest in that possibility, we are beginning to move along. We are awakening our inquisitiveness. That leads us to explore what might be causing our suffering, and we discover the destructive power of ignorance and grasping. This is the truth of the cause of suffering.

The brilliance of this teaching is that right away it gives you something to work with. Instead of dreaming of how things might be or should be, you begin simply with what is right in front of you. You begin to make a transition from feeling victimized: you see that since you are actually responsible for your situation, you yourself can change it. So instead of despairing that “you made your bed, now lie in it,” it is more like “you made your bed, so you can unmake it as well.” This is the third noble truth—cessation, the possibility of freedom. And finally, with great practicality, the Buddha gave detailed instructions on how to move forward. This is the path, the fourth noble truth.

Meditation

Like the view of path of individual liberation, which is the foundation for the entire path, the meditation practices of this yana continue right through the Mahayana and Vajrayana. The central practices are twofold, shamatha and vipashyana—mindfulness and awareness.

Basically, shamatha is the practice of taming the mind; it is a stilling and settling of the mind. Vipashyana means “clear seeing,” and it has two aspects. There is an inquisitive, investigative component, and also a direct perceptual component that comes when the mind relaxes and opens out. Both shamatha and vipashyana are ways of gaining sophistication about the working of your own mind and the play of thoughts and emotions. As a result, you are less captured by your opinions and judgments and not so easily overwhelmed by the intensities of your emotions. There is a quality of kindness and self-acceptance.

Action

The yana of individual liberation is all about slowing down and simplifying. There is a paring down of experience at all levels, with fewer distractions, fewer thoughts, less drama, fewer entanglements. When you act simply, with mindfulness, your actions have more power. You speak when something needs to be said, and you act when action is needed. You are learning how to be, and you manifest the power of simple genuine presence.

In the yana of individual liberation, there is also a quality of restraint. You practice the discipline of refraining from harmful actions. Because you are less caught in speediness of mind, you can recognize the arising of impulsive, negative action and nip it in the bud.

The view, practice, and action of the path of individual liberation set you on the path of dharma. They help you build the mental, emotional, and meditative health you need to grow in your dharmic understanding and realization. They prepare you well for the journey.

Mahayana: The Bodhisattva Path of Wisdom and Compassion

The Mahayana is a natural outgrowth of the yana of individual liberation. It is the simplifying and paring down of the path of individual liberation that makes the expansiveness of Mahayana possible. Doing the hard work of investigating your own nature and your preconceptions about the world changes you in significant ways. You become more self-accepting, gentler, more real and genuine. When you have become a better friend to yourself, you are ready to be a better friend to others.

View

In the Mahayana you see yourself as inextricably connected with all other beings, and because of that your individual path expands and broadens. Your training in the yana of individual liberation has brought you to the point where you sense the underlying inclination of all beings to awaken, and you gain more confidence in your own potential. At the same time, you recognize that focusing on your own development is not enough. You cannot be free from suffering if you know that others around you are still suffering.

So the awareness you have cultivated through sitting practice makes it hard to ignore the suffering of others, and it gives birth to greater empathy and compassion. Likewise, the silence and stillness cultivated in your shamatha practice gives birth to a sense of vastness, openness, and continual expansion. This wide-open quality, since it is free of deception or any boundaries, concepts, or limits, is referred to as emptiness, or shunyata.

Meditation

The practice of sitting meditation continues to be important in the Mahayana. But in addition to the cultivation of mindfulness and awareness, there is an emphasis on the cultivation of the heart and on meditation in action.

The term “meditation” usually refers to more formless practices, such as placing attention on the breathing process. But once the mind is somewhat settled, you can engage in a variety of contemplative exercises as a mindful way of reflecting on a particular subject. This kind of reflection could be about obstacles you need to overcome or it could be about qualities you aspire to cultivate.

In one traditional contemplation, you contemplate the qualities of loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity, known as the four immeasurables. This is not done in a dry or abstract way; you aspire to tap in to the limitless energy of each of these benevolent emotions and direct it outward to beings near and far. So at one and the same time, you are deepen- ing your understanding of these four qualities and you are evoking them on the spot.

Perhaps the most well-known Mahayana practice is that of tonglen, sending and taking. This practice is also referred to as exchanging yourself for others. It is a radical reversal of the habit of putting oneself before others; in this practice, others come first. When others are experiencing difficulty or pain, you breathe that in; when joy or confidence arises within, you breathe that out to benefit others. You practice tonglen in relation to your own mental- emotional process and you practice this in relation to others, starting with those closest to you and extending from there. Tonglen practice challenges our sense of territory, limits, and boundaries; it confronts us with the limits of our thoughts, and the limits of our love and compassion for ourselves and other beings.

In the Mahayana, the practice of tonglen is complemented by the ongoing practice of bringing wisdom and compassion into our ordinary, everyday encounters. This is called meditation in action. Formal practices are like basic training, but the test of that training is how it manifests in your daily life. It is easy to be compassionate in theory, but putting it into practice is not so easy. So along with tonglen practice, you can work with a set of Mahayana slogans called lojong (mind training) that serve as pointed reminders to continue the cultivation of loving-kindness and compassion in the midst of daily life. These powerful little slogans will not let you off the hook.

Although such Mahayana practices as tonglen have become popular, Mahayana wisdom practices are equally important. In the Madhyamaka, or middle way approach, you work with a sophisticated system of logical reasonings to deconstruct your ego-clinging and fixed views about reality. These cut off any escape from immediate experience and leave you groundless, in a kind of no-man’s-land. Although this might sound desolate or devastating, it is simply the pain of emergence from the constraints of our fear and ego-clinging.

A related practice is the systematic contemplation of the different aspects of emptiness. Once again, you are using reasoning mind to realize the nonconceptual. You do so with such diligence, putting so much energy and fuel into the project, that eventually the struggling conceptual mind simply burns itself out.

Action

In the yana of individual liberation you cultivated the discipline of restraint, of refraining from harmful actions. On that basis you can afford to extend yourself. In the Mahayana, your discipline is not only to limit harmful actions but to increase activities that are of benefit to yourself and others. You are challenged to push beyond your comfort zone and be willing to engage fully with the world.

The notion of virtuous action in the Mahayana has great depth. Six fundamental principles serve as guidelines: generosity, discipline, patience, exertion, meditation, and knowledge. These are known as the six transcendent perfections, or paramitas. There is constant interplay among these six and a variety of checks and balances. And underlying all of them is the basic Mahayana principle of putting others before yourself.

There is a subtlety in the approach to action in the Mahayana. If you are attached to the idea of being virtuous, if you are fixated on results, if you want a pat on the back, it is no longer real virtue. You may accomplish a certain level of benefit, but if your actions are less tainted by those kinds of concerns, you can accomplish much more. Without that kind of residue, there is a lightness and humor in your actions, as well as great depth and power.

Vajrayana: The Tantric Path of Indestructible Wakefulness

The third and final yana is the Vajrayana, which is also known as tantra. It is the natural fruition of the groundwork laid by the path of individual liberation, and the expansion of the path in the Mahayana. In the three-yana system, the Vajrayana is the fruition, the endpoint, yet it is also a continuation of what has come before. The Vajrayana does not leave the path of individual liberation and the Mahayana behind; it incorporates the views and practices of the previous two yanas and builds on them.

You gather your energy in the yana of individual liberation and extend out in the Mahayana. In the Vajrayana you dive into reality completely. When you dive in without hesitation, the world is seen as sacred, and your ordinary vision is transformed into sacred outlook. At this point you are already steeped in the view and practices of the buddhadharma, so the time has come to fully manifest what you have learned. It is the Vajrayana that shows you how to do that, and so it is known as the yana of skillful means.

View

In the Vajrayana your view is expansive. It is as if you have been trudging along a mountain trail for miles and miles and finally reach the top, where at long last you have a chance to see the entire panorama. You experience your ordinary world in a fresh way and the most mundane experiences are seen to be infused with sacredness. The Vajrayana view is nontheistic, yet you experience this sacred world as filled with deities, filled with teachers and teaching, filled with symbolism. In the Vajrayan you being to touch in to a realm of boundless space that is both luminous and empty, accommodating birth and death, samsara and nirvana, all phenomena.

Meditation

Vajrayana practices can be divided into those with form and those that are more formless. Naturally, the foundation for embarking on these advanced practices is your training in shamatha and vipashyana, and in the Mahayana mind training and compassion practices.

Visualization practices make use of the mind’s natural tendency to form pictures. In visualization practice you create an image in your mind of a deity, and you evoke the wisdom and power of that deity, identifying the deity with those qualities in your own nature. Visualization practices are done in the context of liturgies, or sadhanas, that include meditation, the recitation of mantras, and ritual gestures, or mudras. In tantra, there are many deities representing different types of realization. For instance, Avalokiteshvara represents compassion and Manjushri represents wisdom. However, it is important to understand that these deities are unlike more well-known theistic concepts, such as a creator God. Tantric deities are luminous yet empty, and they arise and dissolve out of emptiness in the process of visualization. They embody our own enlightened nature.

Vajrayana formless practice is the epitome of simplicity and relaxation. This experience is sometimes referred to as being like an old dog. There is a carefree, confident, and nonstriving approach to meditation and a letting go of pretense. Trungpa Rinpoche talked about this as being content to be the lowest of the low. There is an exhaustion of egoic ambition.

Vajrayana practices are meant to be transmitted directly by an accomplished master to students who are well-trained and prepared to enter into them fully. They are not taken up casually. The per- sonal relationship between teacher and student is paramount. The meeting of the dedication of the teacher and the devotion of the students provides the essential spark for Vajrayana practices to take root.

Action

Vajrayana action, like that of the previous yanas, is based on wisdom and compassion. It has its root in mindfulness and awareness. But at this level, com- passionate activity becomes more radical, even wrathful, and totally uncompromising. Such action is described as having four forms or energies: pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and destroying. There is a no-nonsense approach to obstacles, and a determination to clear away fearlessly anything that threatens to undermine one’s progress on the path to the realization of the sacred, wakeful nature of reality.

In the Vajrayana we recognize that physical gestures, sounds and utterances, and thoughts are all gateways to awakening and should be worked with and respected. We see that all aspects of our experience, and the environment as a whole, are workable on the path to enlightenment. The Vajrayana is a complete world. Once you enter it, every action becomes a message of the teaching. There is no boundary and nowhere to hide.

Treasure

The three-yana journey I have been describing is not a linear journey. You repeatedly circle back to the beginning and start over again. Each time you think you have reached a break- through, you find that there is further to go, and it becomes clear that an accomplishment at one level can become an obstacle at the next. However, you keep going, drawn by the lure of the treasure, the promise of awakening, the yearning for freedom. If you follow the map with enough persistence, maybe you will find it. There it will be: X marks the spot. Or maybe the search itself is the treasure. Maybe you have been carrying the treasure with you all along.

A key aspect of Mahayana practice is that you continually bring compassion and wisdom into balance. There is no real wisdom without compassion, and no real compassion without wisdom. Fundamentally the two are inseparable, but it is possible to lose that balance, so it must continually be restored.