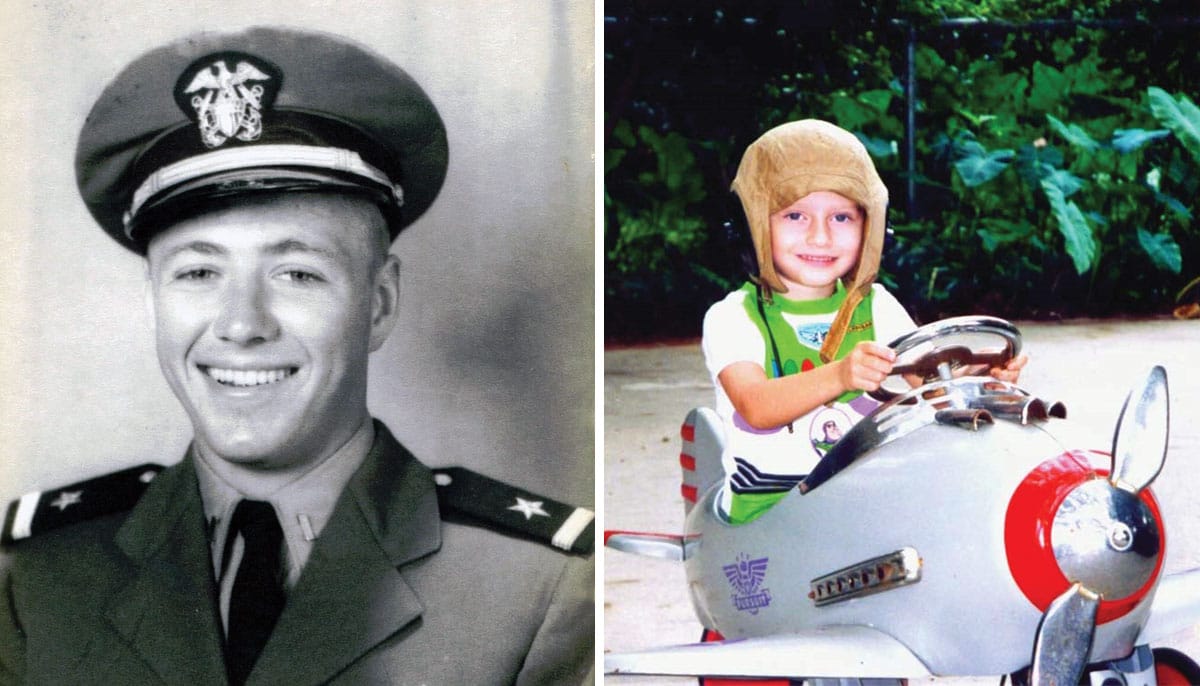

On March 3, 1945, James Huston, a twenty-one-year-old U.S. Navy pilot, flew his final flight. He took off from the USS Natoma Bay, an aircraft carrier engaged in the battle of Iwo Jima. Huston was flying with a squadron of eight pilots, including his friend Jack Larsen, to strike a nearby Japanese transport vessel. Huston’s plane was shot in the nose and crashed in the ocean.

Fifty-three years later, in April of 1998, a couple from Louisiana named Bruce and Andrea Leninger gave birth to a boy. They named him James.

When he was twenty-two months old, James and his father visited a flight museum, and James discovered a fascination with planes—especially World War II aircraft, which he would stare at in awe. James got a video about a Navy flight squad, which he watched repeatedly for weeks.

Within two months, James started saying the phrase, “Airplane crash on fire,” including when he saw his father off on trips at the airport. He would slam his toy planes nose-first into the coffee table, ruining the surface with dozens of scratches.

James started having nightmares, first with screaming, and then with words like, “Airplane crash on fire! Little man can’t get out!”, while thrashing and kicking his legs.

Eventually, James talked to his parents about the crash. James said, “Before I was born, I was a pilot and my airplane got shot in the engine, and it crashed in the water, and that’s how I died.” James said that he flew off of a boat and his plane was shot by the Japanese. When his parents asked the name of the boat, he said “Natoma.”

When his parents asked James who “little man” was, he would say “James” or “me.” When his parents asked if he could remember anyone else, he offered the name “Jack Larsen.” When James was two and a half, he saw a photo of Iwo Jima in a book, and said “My plane got shot down there, Daddy.”

When James Leninger was eleven years old, Jim Tucker came to visit him and his family. Tucker, a psychiatrist from the University of Virginia, is one of the world’s leading researchers on the scientific study of reincarnation or rebirth. He spent two days interviewing the Leninger family, and says that James represents one of the strongest cases of seeming reincarnation that he has ever investigated.

“You’ve got this child with nightmares focusing on plane crashes, who says he was shot down by the Japanese, flew off a ship called ‘Natoma,’ had a friend there named Jack Larsen, his plane got hit in the engine, crashed in the water, quickly sank, and said he was killed at Iwo Jima. We have documentation for all of this,” says Tucker in an interview.

“It turns out there was one guy from the ship Natoma Bay who was killed during the Iwo Jima operations, and everything we have documented from James’ statements fits for this guy’s life.”

Jim Tucker grew up in North Carolina. He was a Southern Baptist, but when he started training in psychiatry, he left behind any religious or spiritual worldview. Years later, he read about the work of a psychiatrist named Ian Stevenson in the local paper.

Stevenson was a well-respected academic who left his position as chair of psychiatry at the University of Virginia in the 1960s to undertake a full-time study of reincarnation. Though his papers never got published in any mainstream scientific journals, he received appreciative reviews in respected publications like The Journal of the American Medical Association, The American Journal of Psychology, and The Lancet. Before his death in 2007, Stevenson handed over much of his work to Tucker at the University of Virginia’s Division of Perceptual Studies.

The first step in researching the possibility of rebirth is the collection of reports of past life memories. Individually, any one report, like James Leninger’s, proves little. But when thousands of the cases are analyzed collectively, they can yield compelling evidence.

After decades of research, the Division of Perceptual Studies now houses 2,500 detailed records of children who have reported memories of past lives. Tucker has written two books summarizing the research, Life Before Life and Return to Life. In Life Before Life, Tucker writes, “The best explanation for the strongest cases is that memories, emotions, and even physical injuries can sometimes carry over from one life to the next.”

Children in rebirth cases generally start making statements about past lives between the ages of two and four and stop by the age of six or seven, the age when most children lose early childhood memories.

A typical case of Tucker’s starts with a communication from a parent whose child has described a past life. Parents often have no prior interest in reincarnation, and they get in touch with Tucker out of distress—their child is describing things there is no logical way they could have experienced. Tucker corresponds with the parents to find out more. If it sounds like a strong case, with the possibility of identifying a previous life, he proceeds.

‘This is not like what you might see on TV, where someone says they were Cleopatra. These kids are typically talking about being an ordinary person.’

When Tucker meets with a family, he interviews the parents, the child, and other potential informants. He fills out an eight-page registration form, and collects records, photographs, and evidence. Eventually, he codes more than two hundred variables for each case into a database.

In the best cases, the researcher meets the family before they’ve identified a suspected previous identity. If the researchers can identify the previous personality (PP) first, they have the opportunity to perform controlled tests.

In a recent case, Tucker met a family whose son remembered fighting in the jungle in the Vietnam War and getting killed in action. The boy gave a name for the PP. When the parents looked up the name, they found that it was a real person. Before doing any further research, they contacted Tucker.

Tucker did a controlled test with the boy, who was five. He showed him eight pairs of photos. In each pair, one photo was related to the soldier’s life and one was not—such as a photo of his high school and a photo of a high school he didn’t go to. For two of the pairs, the boy made no choice. In the remaining six, he chose correctly.

In another case, a seven-year-old girl named Nicole remembered living in a small town, on “C Street,” in the early 1900s. She remembered much of the town having been destroyed by a fire and often talked of wanting to go home. Through research, Tucker hypothesized Nicole was describing Virginia City, Nevada, a small mining town that was destroyed by fire in 1875, where the main road was “C Street.” Tucker traveled to Virginia City with Nicole and her mother. As they drove down the road into the town, Nicole remarked, “They didn’t have these black roads when I lived here before.”

Nicole had described strange memories of her previous life. She said there were trees floating in the water. She said horses walked down the streets. And she talked about a “hooley dance.” In the town, they discovered that there had once been a massive network of river flumes used to transport logs to the town to construct nearby mineshafts. They discovered that wild horses wandered through the streets of the town. And that a “hooley” is a type of Irish dance that was popular there.

“We weren’t able to identify a specific individual,” says Tucker. “But there are parts of the case that are hard to dismiss.”

As her plane was lifting off from Nevada, Nicole burst into tears. “I don’t want to leave here,” she said.

Her mother asked if she really believed Virginia City was her home. “No,” said Nicole. “I know it was.”

Tucker is trying to investigate scientifically a question that has traditionally been the province of religion: what happens after we die? Two of the world’s largest religions, Hinduism and Buddhism, argue that we are reborn.

Certain schools of Buddhism don’t particularly concern themselves with the idea of rebirth, and some modern analysts argue that the Buddha taught it simply as a matter of convenience because it was the accepted belief in the India of his time. Most Buddhists, however, see it as central to the teachings on the suffering of samsara—the wheel of cyclic existence—and nirvana, the state of enlightenment in which one is free from the karma that drives rebirth (although one may still choose to be reborn in order to follow the bodhisattva path of compassion).

Buddhists generally prefer the term “rebirth” to “reincarnation” to differentiate between the Hindu and Buddhist views. The concept of reincarnation generally refers to the transmigration of an atman, or soul, from lifetime to lifetime. This is the Hindu view, and it is how reincarnation is generally understood in the West.

Instead, Buddhism teaches the doctrine of anatman, or non-self, which says there is no permanent, unchanging entity such as a soul. In reality, we are an ever-changing collection of consciousnesses, feelings, perceptions, and impulses that we struggle to hold together to maintain the illusion of a self.

See also: The Buddhist Teachings on Rebirth

In the Buddhist view, the momentum, or “karma,” of this illusory self is carried forward from moment to moment—and from lifetime to lifetime. But it’s not really “you” that is reborn. It’s just the illusion of “you.” When asked what gets reborn, Buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche reportedly said, “Your bad habits.”

For Jim Tucker, though, the spiritual connections—Buddhist or otherwise—are incidental. “I’m purely investigating what the facts show,” he says, “as opposed to how much they may agree or disagree with particular belief systems.”

Rebirth is just one component of a theory of consciousness that Tucker is working on. “The mainstream materialist position is that consciousness is produced by the brain, this meat,” he says. “So consciousness is what some people would call an epiphenomenon, a byproduct.”

He sees it the other way around: our minds don’t exist in the world; the world exists in our minds. Tucker describes waking reality as like a “shared dream,” and when we die, we don’t go to another place. We go into another dream.

Tucker’s dream model parallels some key Buddhist concepts. In Buddhism, reality is described as illusion, often compared to a sleeping dream. In Siddhartha Gautama’s final realization, he reportedly saw the truth of rebirth and recalled all of his past lives. Later that night, he attained enlightenment, exited the cycle of death and rebirth, and earned the title of “Buddha”—which literally means “one who is awake.”

In fact, according to scripture, the Buddha met most—if not all—of Jim Tucker’s six criteria for a proven case of rebirth. Maybe he would have made an interesting case.

Memory is only one phenomenon associated with past lives, and memories alone are not enough to make a case.

In order to proceed with an investigation, Tucker’s team requires that a case meet at least two out of six criteria:

- a specific prediction of rebirth, as in the Tibetan Buddhist tulku system

- a family member (usually the mother) dreaming about the previous personality (PP) coming

- birthmarks or birth defects that seem to correspond to the previous life

- corroborated statements about a previous life

- recognitions by the child of persons or objects connected to the PP

- unusual behaviors connected to the PP

Tucker’s research suggests that, if rebirth is real, much more than memories pass from one life to the next. Many children have behaviors and emotions that seem closely related to their previous life.

Emotionality is a signal of a strong case. The more emotion a child shows when recalling a past life, the stronger their case tends to be. When children start talking about past-life memories, they’re often impassioned. Sometimes they demand to be taken to their “other” family. When talking about their past life, the child might talk in the first person, confuse past and present, and get upset. Sometimes they try to run away.

In one case, a boy named Joey talked about his “other mother” dying in a car accident. Tucker recounts the following scene in Life Before Life: “One night at dinner when he was almost four years old, he stood up in his chair and appeared pale as he looked intently at his mother and said, ‘You are not my family—my family is dead.’ He cried quietly for a minute as a tear rolled down his cheek, then he sat back down and continued with his meal.”

In another unsettling case, a British boy recalled the life of a German WWII pilot. At age two, he started talking about crashing his plane while on a bombing mission over England. When he learned to draw, he drew swastikas and eagles. He goose-stepped and did the Nazi salute. He wanted to live in Germany, and had an unusual taste for sausages and thick soups.

In some cases, these emotions manifest in symptoms that look like post-traumatic stress disorder, but without any obvious trauma in this life. Some of these children engage in “post-traumatic play” in which they act out their trauma—often the way the PP died—with toys. One boy repeatedly acted out his PP’s suicide, pretending a stick was a rifle and putting it under his chin. In the cases where the PP died unnaturally, more than a third of the children had phobias related to the mode of death. Among the children whose PP died by drowning, a majority were afraid of water. ‚

Positive attributes can also carry over, seemingly. In almost one in ten cases, parents report that their child has an unusual skill related to the previous life. Some of those cases involve “xenoglossy,” the ability to speak or write a language one couldn’t have learned by normal means.

A two-year-old boy named Hunter remembered verifiable details from a past life as a famous pro golfer. Hunter took toy golf clubs everywhere he went. He started golf lessons three years ahead of the minimum age, and his instructors called him a prodigy. By age seven, he had competed in fifty junior tournaments, winning forty-one.

In many cases, the child is born with marks or birth defects that seem connected to wounds on the PP’s body. Ian Stevenson reported two hundred such cases in his monograph Reincarnation and Biology, including several in which a child who remembered having been shot had a small, round birthmark (matching a bullet entrance wound) and, on the other side of their body, a larger, irregularly-shaped birthmark (matching a bullet exit wound).

Patrick, born in the Midwest in 1992, had several notable birthmarks. His older half-brother, Kevin, had died of cancer twelve years before Patrick was born. Kevin was in good health until he was sixteen months old, when he developed a limp, caused by cancer. He was admitted to the hospital, and doctors saw that he had a swelling above his right ear, also caused by the disease. His left eye was protruding and bleeding slightly, and he eventually went blind in that eye. The doctors gave him fluid through an IV inserted in the right side of his neck. He died within a few months.

Soon after Patrick’s birth, his mother noticed a dark line on his neck, exactly where Kevin’s IV had been; an opacity in his left eye, where Kevin’s eye had protruded; and a bump above his right ear, where Kevin had swelling. When he began to walk, Patrick had a limp, like his brother. At age four, he began recalling memories from Kevin’s life and saying he had been Kevin.

See also: A comparison of modern reincarnation research and the traditional Buddhist views

Tucker says there is no perfect case, but, collectively, the research becomes hard to rationalize with normal explanations. Research has demonstrated that children in past-life memory cases are no more prone to fantasies, suggestions, or dissociation than other children. Regarding coincidence, statisticians have declined to do statistical analyses because the cases involve too many complex factors, but one statistician commented, “phrases like ‘highly improbable’ and ‘extremely rare’ come to mind.” For the stronger cases, the most feasible explanation is elaborate fraud, but it’s hard to see any reason why a family would make up such a story. Often, reincarnation actually violates their belief system, and many families remain anonymous, anyway.

“This is not like what you might see on TV, where someone says they were Cleopatra,” says Tucker. “These kids are typically talking about being an ordinary person. The child has numerous memories of a nondescript life.”

Tucker quotes the late astronomer and science writer Carl Sagan, whose last book was The Demon Haunted World, a repudiation of pseudoscience and a classic work on skepticism. In it, Sagan wrote that there were three paranormal phenomena he believed deserve serious study, the third being “that young children sometimes report details of a previous life, which upon checking turn out to be accurate and which they could not have known about in any other way than reincarnation.”

Sagan didn’t say he believed in reincarnation, but he felt the research had yielded enough evidence that it deserved further study. Until an idea is disproven, Sagan said, it’s critical that we engage with the idea with openness and ruthless scrutiny. “This,” he wrote, “is how deep truths are winnowed from deep nonsense.”