Growing up outside Philadelphia back in the 1980s, I found myself attracted to practicing meditation to attain enlightenment. When I was first exposed to Buddhism, I assumed that silent sitting meditation, with or without the single-minded contemplation of koans, was the only authentic form of Buddhist practice. Despite my aspirations and the availability of clear instructions on Zen meditation in the many books I was reading, I couldn’t bring myself to just sit down and shut up.

Then one night in Philadelphia, I was approached by a woman who handed me a card and asked if I would like to go to a Buddhist meeting. Printed on the card was what I now know as the daimoku (title), the Japanese pronunciation of a mantra derived from the title of the Lotus Sutra, “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.” This is how I was introduced to the Nichiren Buddhist practice of chanting for buddhahood.

Since then, I’ve learned that while silent contemplative meditation may have been the practice of Shakyamuni Buddha and some groups of monastics and dedicated lay practitioners, the vast majority of Buddhists in Asia—both now and for more than two millennia—have practiced some form of chanting. For a bit of perspective on this, consider that in 2021 the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan reported that in their nation there were approximately 22 million members of the various Pure Land schools that focus on chanting the nembutsu (recollection of a buddha), in the form of “Namu Amida Butsu,” meaning “Devotion to the Buddha of Infinite Light.” There were 11 million members of the various forms of Nichiren Buddhism who chant the daimoku and 9 million members of other schools who also chant nembutsu as well as other mantras as part of their regular practices. However, there were only about 5.3 million members of the various Zen schools whose primary practice is silent sitting meditation. In Korea, China, Vietnam, and even Tibet, the chanting of the nembutsu or other mantras, such as “Om Mani Padme Hum,” is likewise ubiquitous.

You might think that the historical Gautama Buddha would have looked askance at the practice of chanting as opposed to silent contemplative meditation. Yet, even in the Buddha’s pre-Mahayana discourses, we find him praising the practice of recollection of the Buddha, the dharma, the sangha, virtuous behavior, generosity, or the various benevolent deities. By recollecting such subjects, the practitioner is able to overcome greed, hatred, and delusion, become tranquil and at ease in body and mind, dwell in balance, and gain inspiration in the meaning of the dharma, among various other benefits.

These recollection practices may have started out as the verbalized or silent recitation of the respective admirable and beneficial qualities of the subject of meditation. Eventually, practices such as the recollection of the Buddha also involved the visualization of the Buddha and his transcendent characteristics. Over time, such elaborations were refined and simplified, especially for those not engaged in full-time monastic practice. The recollection of the Buddha and dharma evolved into the nembutsu and the daimoku respectively. These short mantras are now both used to keep the mind centered on a subject that cannot be captured by discursive words or elaborate concepts.

This evolution of recollection to chanting the nembutsu and daimoku could be likened to how the contemplation of Zen koans was refined by Dahui Zongao (1089–1163) into the practice of huatou (head of speech) wherein a single word or phrase from a koan is used as the subject of contemplation. In fact, later Chan (Zen) teachers would even use the nembutsu as a huatou. In using the nembutsu in that way, the one who is chanting is to ask themselves, “Who is it who chants the nembutsu?”

I did eventually learn to practice silent sitting, but my main dharma gate was the Nichiren Buddhist practice of chanting the daimoku. Once I moved to California, I came into contact with the Nichiren Shu, the main confederation of Nichiren Buddhist lineages that had been transplanted in North America by Japanese immigrants. Their first temple was established in Los Angeles in 1915.

It was at the LA temple that I was introduced to shodaigyo meditation, which combines the practice of silent sitting with the chanting of the daimoku to the beat of a taiko drum. I found it at once calming and exhilarating. Many years later, while undergoing monastic training for ordination as a Nichiren Shu priest, I would have the honor of learning more about this practice from Tairyu Gondo (1928–2009), the disciple of Nichijun Yukawa (1876–1968) who established the practice of shodaigyo meditation in 1957. Though shodaigyo meditation is a relatively new practice that is not as elaborate as a regular service, I think it provides a good way of showcasing how the daimoku is practiced in Nichiren Shu and the way in which it relates to other traditional forms of Buddhist practice.

Though shodaigyo is ideally practiced with others under the direction of a Nichiren Shu priest or lay leader, I would like to offer instructions for trying this practice on your own. This version is derived from Tairyu Gondo’s book The Journey of the Path of Righteousness.

1. Salutation

Begin in a kneeling posture called seiza (correct sitting), preferably on a zabuton (flat cushion). If you’re unable to kneel, you may use a seiza bench or a chair. The important thing is to sit in a stable upright posture facing the honzon (focus of devotion).

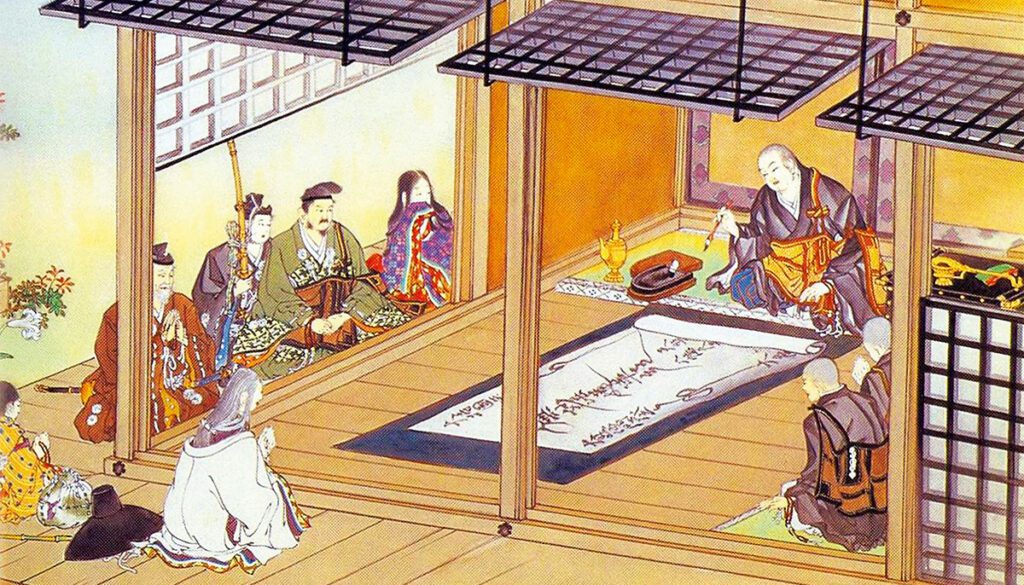

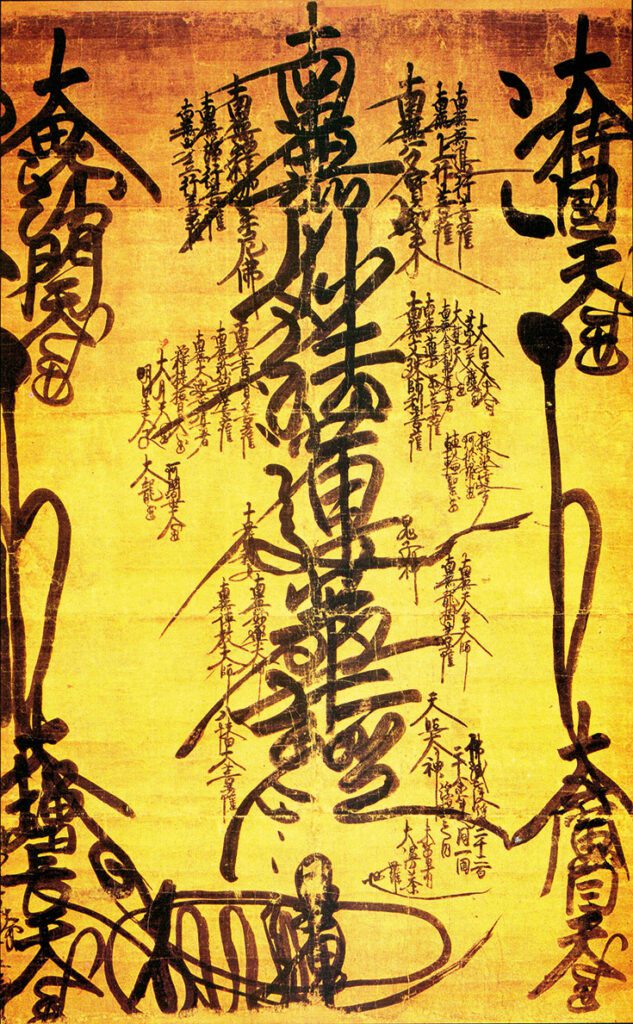

The focus of devotion in Nichiren Buddhism is a depiction of the part of the Lotus Sutra when Shakyamuni Buddha reveals that his buddhahood is unborn and deathless (and therefore never truly absent from all of life) and transmits his wonderful dharma to all beings. This is often in the form of a calligraphic mandala upon which the daimoku is inscribed. Sometimes, as in many temples, it is depicted by a stupa inscribed with the daimoku that is flanked by Shakyamuni Buddha and Many Treasures Buddha. If you do not have a shrine, it is sufficient to simply imagine that you are kneeling in the presence of the Eternal Shakyamuni Buddha.

Make a deep bow while facing the honzon. From the kneeling position, slowly lower your forehead until it is almost grazing the floor. At the same time, raise your hands up to ear level, with palms up and all fingers straight and extended. Both elbows should be touching the floor just in front of the knees. Imagine that the Eternal Buddha is standing on your palms and that you are reverently raising him up. This deep bow is an expression of personal humility and gratitude to the Eternal Buddha.

2. Acknowledge the Place of Awakening

Sitting upright again, read or recite the following passage from the Lotus Sutra: “Know this, the place where the stupa is erected is the place of enlightenment. Here the buddhas attained unsurpassed, complete, and perfect awakening. Here the buddhas turned the wheel of the dharma. Here the buddhas entered final nirvana.”

Reading or reciting this verse acknowledges that the place where you are right now is a buddha-land because you’re practicing there. In other words, you are in the presence of the Eternal Buddha.

3. Reverence for the Three Treasures

Read or recite the following verses of reverence for the three treasures that Buddhists take refuge in as interpreted by the Nichiren tradition. After each verse, bow deeply as described in step one.

Honor be to the Eternal Shakyamuni Buddha, our Original Teacher, who attained awakening in the remotest past.

Honor be to the Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma, the Teaching of Equality, the Great Wisdom, the One Vehicle.

Honor be to our Original Teacher Superior Practice, our Founder, the Great Bodhisattva Nichiren Shonin.

4. Practice to Purify the Mind

Sit in silence for five to ten minutes while focusing on mindfulness of the breath. Put your hands in hokkai jo-in (dharma-realm meditation mudra), wherein the left palm rests upon the right palm with the thumb-tips lightly touching. Focus on gentle, deep, and strong breathing from the lower belly. Calm your mind and heart as a preparation for the chanting of the daimoku.

5. The Practice of Truly Reciting

Put your hands in gassho (joining the palms together), a gesture of reverence and devotion, and begin chanting Namu Myoho Renge Kyo with a six-beat cadence. “Namu” receives one beat, while “myo,” “ho,” “ren,” “ge,” and “kyo” each receive a single beat. At a fast tempo, the “u” sound in “Namu” is often elided.

At first, the tempo should be slow. After ten minutes, gradually increase the tempo like a train building up steam. Continue this fast tempo for half an hour and then slow again for another ten minutes. After that, transition gradually into a very slow tempo for the last five minutes. Please feel free to vary these times to suit your needs for your own private practice.

In a temple, the tempo is set with percussion instruments such as a taiko drum. If you want to use a drum or other instrument, simply strike the drum lightly at “Namu,” moderately for the middle four beats of “myo-ho-ren-ge,” and a little harder for “kyo.” At the fastest pace, however, the strikes should all be even and monotone.

Through this rhythmic chanting, you may find that your mind and heart are integrated with the daimoku so that you experience shodai zanmai (the samadhi of chanting the title). As Tairyu Gondo explained in The Journey of the Path of Righteousness, “The state of chanting is the state of Buddha, the words of chanting are the words of Buddha, and the heart of chanting is the heart of Buddha. This state of becoming a Buddha is called sokushin jobutsu (becoming a Buddha with this very body).”

6. Practice to Deepen Faith

Return your hands to hokkai jo-in and continue to recite the daimoku silently. With each breath, mentally recite a single character of the daimoku (Na, mu, myo, ho, ren, ge, and kyo), cycling through all seven of them. In this period of meditation, you can peacefully abide in the power of the prior vocalized chanting, maintain a sense of receptivity to the meritorious qualities of buddhahood imparted by the daimoku, and aspire to actualize these qualities in your life.

7. Dedication of Merit

The merit gained from Mahayana Buddhist practices such as chanting the daimoku can be shared with all beings and directed to the attainment of buddhahood.

Offer a dedication of merit using the following passage from the Lotus Sutra: “May the merits we have accumulated by this offering be distributed among all living beings, and may we and all living beings attain the enlightenment of the Buddha!”

8. Four Bodhisattva Vows

Recite the four bodhisattva vows: “Sentient beings are infinite, I vow to liberate them all. Defilements are innumerable, I vow to resolve them all. Dharma gates are inexhaustible, I vow to know them all. The way of the Buddha is unsurpassed, I vow to become it.”

These are the general vows of bodhisattvas who aspire to buddhahood taken from the Sutra of the Jeweled Necklace of Bodhisattva Practice. They were popularized in East Asian Buddhism by Tiantai Zhiyi (538–597). The daimoku is understood to be the practice that enables practitioners to fulfill these vows.

9. Concluding the Practice

Recite the following dedication: “From this body, until I attain buddhahood, I will strive to uphold Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.”

We can understand the daimoku as expressing the merits of buddhahood, the dharma, and what is transmitted by the sangha led by Nichiren. So, by striving to uphold it, we are also taking refuge in the three treasures.

Bring the practice to a conclusion with a final deep bow.

My experience with shodaigyo practice showed me that chanting is indeed inclusive of the twin aims of Buddhist meditation generally: calming the mind and opening the way to insight. Specifically, the daimoku is a recognition that buddhahood—while elusive—is also all-pervasive and all-embracing. The daimoku is an affirmation that buddhahood can be realized and actualized in our lives here and now.

This article is from the March 2024 issue of Lion’s Roar magazine.