My first experiences learning to meditate were with my late father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. He was a revered meditation teacher, but he lived a very simple life, spending most of his time in a small hermitage on the outskirts of the Kathmandu Valley. Some of my most precious memories are of the years I first learned to meditate, sitting at the foot of a traditional “meditation box” that served as both his bed and meditation space.

One moment I will never forget was the time he introduced me to the principle of buddhanature. I was sitting on the floor trying to meditate, but the village dogs were especially annoying that day and I couldn’t stay focused. My father, sensing my frustration, gently said, “Amé”—a Tibetan term of endearment that means something like “dear”—and then pointed out the window to the barking dogs.

The only difference between a buddha and everyone else is that a buddha recognizes their own true nature, while all the beings suffering in samsara do not.

“Did you know,” he said, “that the true nature of all those dogs you hear barking is the same as the true nature of all the buddhas?” He then pointed to a statue of the Buddha on his shrine. “And you have this true nature as well. You, those dogs, the Buddha here—you all have buddhanature. The only difference between a buddha and everyone else is that a buddha recognizes their own true nature, while all the beings suffering in samsara do not.”

I will never forget those words.

I wish I could say that I experienced a profound awakening when I heard them, like the great arhats of the past who became enlightened from hearing a few simple words from the Buddha. The truth is that I didn’t believe them.

What had motivated me to start meditating in the first place were the crippling panic attacks that followed me around like a shadow. The idea that I was already a buddha was far from my actual experience. I could only see my flaws and shortcomings.

So when he told me that my own mind was fundamentally pure, and that the path of meditation was simply the process of recognizing qualities that I already had, these were nothing more than words and ideas to me. I didn’t doubt him, or that the idea of buddhanature was true. I just didn’t believe these teachings applied to me.

The Path to Buddhanature

There are a few individuals who can recognize their own buddhanature the moment they hear the teachings. These are called the “instantaneous” type, according to tradition, but they are exceedingly rare. Most of us need a step-by-step path to follow. We need practical tools that help us translate the profound principle of buddhanature into direct experience, so that it becomes more than an inspiring concept we read about in books.

As I said, my first reaction to the idea of buddhanature was doubt, but in a way, it was a healthy doubt. I didn’t really believe that my own mind, in its present state, was fundamentally pure, but I was open enough to the idea that I kept at it. My father taught me how to meditate, and although I was lazy and struggled to keep up my daily meditation practice, I kept going. I stayed on the path.

What I didn’t quite realize at the time was that he was teaching me an ingeniously designed path of meditation, one that opens the mind to new possibilities. Some of the practices I learned tapped into the power of my overactive imagination. Other meditations helped me see how daily experiences like falling asleep and dreaming could be powerful gateways to self-discovery. And some teachings—the ones my father seemed to treasure above all others—were meant to directly point out to me the awakened nature of awareness itself.

The Fruitional Path

In sharing these teachings with me, as he did with countless others, he was passing on the core teachings of Buddhist tantra, also known as Vajrayana, the “Indestructible Vehicle.” Although Buddhist tantra has its origins in ancient India, and is found in some other Buddhist traditions, it is mainly identified today with Tibetan Buddhism.

It is often said that what sets the Vajrayana apart from other styles of Buddhist meditation is not the view—meaning the core principles that underlie this approach—but rather the swift and transformative types of meditation it employs. There are certainly debates in the tradition about the view of the Vajrayana, and whether or not it is more profound than the perspective of other approaches. What no one disputes, however, is that the Vajrayana approach to meditation is uniquely effective when it comes to accessing buddhanature.

So in this four-part series in Lion’s Roar, I will explore the most important forms of meditation in Buddhist tantra. In this, the first of the series, I will give an overview of the tradition as a path to realizing our buddhanature. The articles to follow in subsequent issues will focus on the three stages of Vajrayana practice: the development stage, the completion stage, and the path of liberation.

Taken together, these three stages of the Vajrayana are referred to as the “fruitional path.” This esoteric term means that there is no goal, or “fruition,” that one seeks to obtain as a result of the practice. From the Vajrayana point of view, the “goal”—meaning the state of awakening or buddhahood—is already here. We are already buddhas. We simply do not recognize that we are. In the Vajrayana, meditation is nothing more than the process of recognizing that we are buddhas, and then nurturing that recognition.

No Obstacles, Only Opportunities

In some strands of Tibetan Buddhism, awakening is what happens at the end of a long, arduous journey. We root out the many impurities in our minds. We pinpoint the mental and emotional states that get in the way of our path to awakening and eliminate them. When we get angry, we generate loving-kindness to counteract the “poison,” or klesha, in our mind. When we experience lust or desire, we contemplate the unsavory qualities of the thing we long for. The path is a long process of identifying and correcting our endless problems and shortcomings.

In the Vajrayana, there are actually no poisons, and so there is no need for antidotes.

This might sound absurd. If we don’t get rid of anger and other toxic states of mind, how can we possibly find our way out of samsara?

This is precisely the question my father was answering when he told me that the dog and I had the same awakened nature as the Buddha. He was trying to tell me that the path of meditation is not about trying to get rid of our shadows and inner demons. In the Vajrayana, meditation is meant to help us recognize the true nature of these experiences, not destroy them.

Seeking a remedy to counteract them, or even trying to transform them, only solidifies the view that they are problems.

But no matter how many times my father reminded me about buddhanature, I struggled to see myself as he did. I looked at my own mind and saw an anxious mess. It was filled with panic and fear and it created tremendous suffering. This led me to an obvious conclusion: if my suffering was due to these painful thoughts and feelings, then surely I must get rid of them if I wanted any peace and happiness in life.

You might not struggle with anxiety or panic like I did, but unless you’re one of those “instantaneous types” who gets enlightened in a single moment, you likely have your own shadows and inner demons. Maybe you have a short temper. Maybe you procrastinate, or feel lonely, or get depressed. We all wrestle with our thoughts, feelings, and impulses, and much of our pain and suffering is due to the endless struggle we have with our own minds.

Meditation is not a way to win this inner power struggle. The Vajrayana approach is to change the entire paradigm. Rather than trying to eliminate our perceived flaws, we treat them as opportunities and use the path of meditation to explore them and discover their true nature. We use every aspect of our inner experience as a gateway to recognizing the empty, luminous purity of our buddhanature.

The Three Stages of the Vajrayana Path

For me, just hearing about buddhanature was not enough. I needed a process, a path. I needed a practical way to see buddhanature for myself, or more accurately, to see it within myself. This is the true specialty of the Vajrayana. It is filled with creative techniques and colorful methods to help us taste buddhanature for ourselves.

There are three different styles of meditation in the Vajrayana tradition. These are known as the “three stages”: the development stage, the completion stage with marks, and the completion stage without marks, also known as the path of liberation.

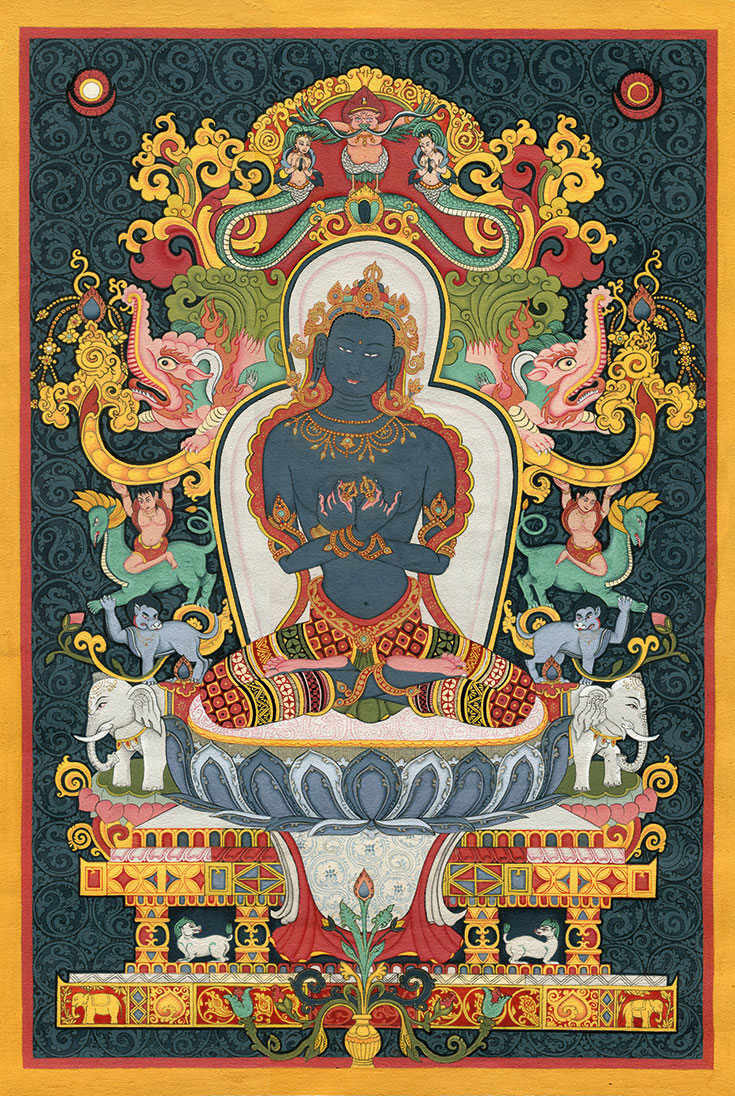

The first of these three, the development stage, transforms impure perception into pure perception by using the imagination and symbolic imagery. Like all forms of meditation in the Vajrayana tradition, the development stage is based on the view that we are all buddhas who have simply not recognized who we truly are. To bring us closer to recognizing our true nature, this style of practice harnesses the power of our restless imagination. Instead of reliving our past mistakes and imagining future scenarios that may never happen, we imagine ourselves as perfectly awakened buddhas. We imagine that we are the very embodiment of wisdom and compassion. We imagine our surroundings as a pure realm, and all other living creatures as our fellow buddhas. In short, development stage practice helps us to see ourselves and the world through the lens of buddhanature.

The second stage of Vajrayana practice, the completion stage with marks, consists of the so-called “inner yogas” such as the famed six dharmas of Naropa. These inner yogas take ordinary experiences and emotions as opportunities to access buddhanature. Some forms of meditation, like the practice of tummo, or “inner heat,” do this by working with the energetic currents and channels of the so-called “subtle body.” Others, like the practice of dream yoga and deep sleep luminosity meditation, use the rhythms of life experience as gateways to buddhanature. There are even practices that help us to recognize the stages of the dying process so we can gain access to the “mother luminosity” that dawns at the moment of death.

The third and final approach, the completion stage without marks, is known as “the path of liberation.” This path includes the nature of mind practices of Mahamudra and Dzogchen, simple yet profound forms of meditation that help us to recognize the true nature of our minds.

Like beggars with treasure buried beneath our very feet, the only thing we need to do is recognize what we already possess.

This typically begins when we receive “pointing out” instructions from a qualified teacher. These instructions help us to experience on the spot the mind’s empty, luminous nature, the nondual essence of pure awareness. Then, once we recognize this pure awareness for ourselves, the practice is exceedingly simple: we return to that recognition over and over until pure awareness is so familiar to us that we never lose touch with it.

Remember Who You Truly Are

Admittedly, it’s easy to get lost in the details when it comes to Vajrayana Buddhism. The Vajrayana is not known for its Zen-like simplicity. The strength of the Vajrayana lies in its richness. It is a tradition filled with powerful methods and transformative insights. The rich array of practices mirrors the complexity of our minds, and there are more than enough styles of practice for each of us to find a path that fits our own strengths and predispositions.

And yet, despite the great diversity of this tradition, the many stages and styles of practice in the Vajrayana share one basic feature: they all point us back to our true nature. As my father taught me so many years ago, there is no fundamental difference between us and the Buddha. Our minds are pure, perfect, and awake, just as his was. Like beggars with treasure buried beneath our very feet, the only thing we need to do is recognize what we already possess. The entire path of Vajrayana meditation is nothing more than a path that leads us back to ourselves. For all the complexity of the Vajrayana, it’s that simple.