The body is the bodhi tree;

The mind is like a bright mirror standing.

Take care to wipe it all the time.

And allow no dust to cling.

—Shen-Hsiu

Not far from Osaka, deep in the forest, there is a 1,400-year-old Buddhist temple called Anraku-ji, which in Japanese means “peaceful, at ease.” But the young priest who took over the care and upkeep of Anraku-ji not long ago, Toshiro Ogama was his name, felt neither truly peaceful nor at ease, and having said something as puzzling as that, it is now necessary, of course, to tell you why.

When Toshiro Ogama was fifteen, both his parents were killed in an automobile accident in Kyoto. An only child, he was suddenly an orphan. His parents’ funeral was conducted by a priest in the Pure Land tradition. At the crematorium, they were incinerated at 800 degrees centigrade. Their bodies burned steadily for two hours. They had a thirty-minute cooling-down period. Finally, their bones were crushed and mixed with their ashes—all total, his parents each weighed two pounds at the end—and they were given back to Toshiro in two white urns. Those containers, which he kept and placed beside the altar at Anraku-ji, led him all his adult life to listen attentively whenever he heard the Buddhist teachings. And what more?

Well, he was painfully shy and, like the English scientist Henry Cavendish, could barely speak to one person, and never to two at once, since four eyes looking at him made Toshiro stammer. At eighteen, he entered Shogen-ji Monastery and devoted four years to rigorous training, living on a prison diet of cheap rice and boiled potatoes in bland soup. He later passed his examinations at Komazawa University, where many Soto Zen monks have studied, but after this Toshiro decided he did not want to teach or try to work his way up through the politically treacherous Buddhist hierarchy. The rigid religious pecking order was brutally competitive, and had corrupted the sangha, the community of Buddhist practitioners, with the greed and hypocrisy of the world. Or at least this was what Toshiro told himself, since he was unable to speak to anyone about his real Zen fears, and why he sometimes felt like a failure, an outright fraud.

He looked around for an abandoned temple that he might repair, manage, and perhaps turn into his own private sanctuary from all the suffering and unpredictable messiness of the social world.

Knowing he didn’t have the family connections or the constitution to rise very high in the religious power structure, Toshiro chose instead to take a freelance job translating bestselling American books for Hayakawa Shobo, a publishing company in Tokyo, and he looked around for an abandoned temple that he might repair, manage, and perhaps turn into his own private sanctuary from all the suffering and unpredictable messiness of the social world. Across Japan, there are thousands of these empty, wooden buildings falling into disrepair, full of termites and rats, with tubers growing through the floorboards, as if each was a vivid illustration of how everything on this planet was so provisional, with things arising and being unraveled in a fortnight, a fact that Toshiro had meditated on deeply, day and night, since the death of his parents.

So when he was granted permission to move into Anraku-ji, the young priest felt, at least for his first year there, a contentment much like that described by Thoreau at Walden Pond. He had no wealthy parishioners or temple supporters paying his salary. Whatever he did at the temple was voluntary, with no strings attached, paid for by his translation work and done for its own rewards. With great care, he spent a year remodeling Anraku-ji’s small main hall and adjoining house, quietly chanting to himself as he worked. He pruned branches, sawed tree limbs, and raked leaves. He trimmed bushes, did weeding and transplanting, and drifted off to sleep to the sound of crickets, bullfrogs, and an owl that each night soothed him like music. Sometimes he talked to himself as he worked, which was a great embarrassment when he caught himself doing it, so he kept a cat to have something to talk to and cover up his habit. He was alone at Anraku-ji, but not lonely, and he decided a man could do far worse than this.

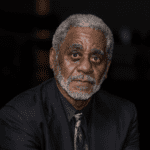

Thus things stood when one afternoon a pilgrim from America arrived unannounced on the steps of his temple. This did not please Toshiro at all because, traditionally, the Japanese do not like surprises. She was a bubbly, effervescent black American about forty years old, with an uptilted nose, a smile that lit up her eyes behind her gold-framed, oval glasses, and long chestnut hair pinned behind her neck by a plastic comb. At first, Toshiro felt ambushed by her beauty. Then he had the uncanny feeling he should know her, but wasn’t sure why. He said, “Konnichiwa” (Japanese for “Good afternoon”), and when she didn’t answer, he said in English, “Are you lost?”

That question made her lips lift in a smile. “Aren’t we all lost? Are you Toshiro Ogama-san?”

“Yes.”

“And are you accepting students? My name is Cynthia Tucker. You’re translating one of my books for Hayakawa Shobo. I would have called first, but you don’t have a phone listed. I’m in Japan for a month and a half, lecturing for the State Department and—well, since I’m here, and have a little free time, I was hoping to meet you, and discuss any problems you might have with American words in my book, and maybe get your help with my practice of meditation.” Now she laughed, taking off her glasses. “Roshi, I think I need a lot of help.”

“I…” Toshiro said, hesitating, “I’m not a teacher.”

“But you are the abbot of this beautiful temple, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Well, if it’s all right, I’d love to stay a few days and—”

“Stay?” His voice slipped a scale.

“Yes, visit with you for awhile and ask a few questions.” He was amused that Tucker said this standing under the sign, posted at every Zen temple and monastery, that meant Look Under Your Feet (for the answers), but this pilgrim did not, of course, read Japanese. “I can make myself useful,” she said. “And I won’t be a bother. Maybe I can help you in some way, too.”

As she spoke, and as he studied her more closely— her flower-patterned blouse, sandals, and white slacks, how early afternoon sunlight was like liquid copper in her hair—Toshiro slowly realized that among the five books he was leisurely translating for Hayakawa Shobo there was one by a Cynthia Tucker, a Sanskrit scholar in the Asian Languages and Literature Department at the University of Washington. Her author’s bio and American newspaper interviews had told him she’d survived colon cancer and two divorces, had no children, taught courses in Eastern philosophy, and described herself whimsically as a Baptist-Buddhist. Her book, The Power of a Quiet Mind, was a 300-page volume interpreting the dharma in terms that addressed the trials and tribulations of black Americans.

Toshiro was only two chapters into his translation, but he’d found her work electrifying—even culturally necessary. Her prose was incandescent, shimmering with the right thought of all buddhas, but in the context of a black American in the twenty-first-century. Toshiro also found this ironic. In Japan, the old ways and old wisdom had become antique after World War II. The traditions of Soto and Rinzai Zen held little interest for the younger, business-minded generation of Japanese who seemed quite satisfied pursuing the goods of the world and being salarymen. But the Americans? Since the 1960s, they had become passionate about the dharma, even when they got it wrong, and he often suspected that much of the continuation of Asian spiritual traditions might fall to them, the gaijin (foreigners) of North America, who had grown weary of materialism. As much as he valued his privacy at the temple, he saw how impolite it would be to turn this very distinguished visitor away. He wasn’t happy about the prospect of having to be entertaining, but it couldn’t be helped. If he didn’t welcome Tucker, her publisher—his boss— would be displeased. Even so, he had always been awkward around people and he felt afraid of this situation.

The young priest brought his palms together in the gesture of gratitude and veneration, called gassho, and made a quick bow.

“Forgive me for not recognizing you at first. I think your book—and you—are wonderful, and you can help me with some of the words,” Toshiro said. “But I don’t think you should stay too long. One day only. I don’t see people often, and I’m not such a good teacher of the buddhadharma. Really, I don’t know anything.”

“Oh, that’s hard to believe,” she said, the corners of her eyes crinkling as she smiled. “I’ve read that all beings are potential buddhas. Anyone or anything can bring us to a sudden awakening—the timbre of a bell, an autumn rose, the extinguishing of a candle. Anything!”

“I’ve read that all beings are potential buddhas. Anyone or anything can bring us to a sudden awakening—the timbre of a bell, an autumn rose, the extinguishing of a candle. Anything!”

Toshiro’s eyes lost focus when she said that. She knew her stuff, and that made his heart give a very slight jump. How would she judge him if she knew the depths of his own failure? The priest invited the pilgrim inside, offering her a cup of rice wine and a plate of rice crackers. He showed her around the temple, the two of them sometimes walking out of step in their stocking feet and bumping each other as they conversed for half the afternoon about English grammar, with Tucker sometimes placing her hand gently on his shoulder, and peppering him with questions that made Toshiro’s stomach chew itself—questions like, “What time do you get up? How often do you shave your head? Is your tongue on the roof of your mouth when you meditate? Do you eat meat, Roshi? Why are Zen priests in Japan allowed to get married, but not those in China?” Toshiro noticed his palms were getting wet, and wiped them on his shirt, but his arm still tingled with pleasure where she had touched him. He excused himself, saying he needed to work awhile on the stone garden he was creating. He repeated his apology, “I am the poorest of practitioners. You must ask someone else these questions. And not stay more than one night. People in the village will talk if a woman sleeps at the temple. And don’t call me roshi.”

“I understand, I’ll leave,” Tucker said, pulling back her head in surprise, and he could feel her smile go frozen. “But, Ogama-san, since I’ve come all this way across the Pacific Ocean, please give me something to do for the temple. I insist. I want to serve. I could make a donation, but assistant professors don’t earn very much. I’d prefer to work. I could help you in your garden.”

Not wanting that, and because the words left his mouth before his brain could catch them, he told Tucker that cleaning out one of the small storage rooms at the hinder part of the main hall, which contained items left by the temple’s last abbot fifty years ago, was a chore he’d been putting off since he moved into Anraku-ji. He gave her a broom, a mop, and a pail, then Toshiro, his stomach tied in knots, hurried outside.

For the rest of the afternoon, he pottered about in the stone garden, but he was in fact hiding from her, and wondering what terrible karma had brought this always questioning American to Anraku-ji. He was certain she would discover that, as a Zen priest, he was a living lie. He knew all the texts, all the traditional rituals, everything about ceremonial training and temple management, but to his knowledge he had never directly experienced enlightenment. He feared he would never grasp satori during his lifetime. It would take a thousand rebirths for the doors of dharma to crack open even a little for one as stalled on the path by sorrow as Toshiro Ogama. In Japanese, there was a word for people like him: Nise b zu. It meant “imitation priest.” And that was surely what Cynthia Tucker would judge him to be if he let her get too close, or linger too long on the temple grounds. If he was to save face, the only solution, as far as he could see, was to demand that she leave immediately.

At twilight, Toshiro tramped back to the main hall, intending to do just that. But what happened next, he had not expected. He found his visitor standing outside the storeroom, her hair lightly powdered with gray dust, and heaped up around her in crates and cardboard boxes were treasures he never knew the temple contained. She had unearthed Buddhist prayers, written a hundred years before in delicate calligraphy on rice paper thin as theater scrim, and wall hangings elaborately painted on silk (these were called kakemono) that whispered of people who had passed through the temple long before he was born—past lives that were all the more precious because they were ephemeral, a flicker-flash of beauty against the backdrop of eternity. There were also large tin canisters of film, a battered canvas screen, and a movie projector from the 1950s, which Tucker was cleaning with a moistened strip of cloth. When Toshiro stepped closer, she looked up, smiling, and said:

“When I was a little girl, my parents had a creaky old projector kind of like this one. I think I can get it working, if you’d like to watch whatever is in those tin containers.”

“Yes,” said Toshiro, “I do.” He picked up one of the canisters and read the yellowed label on top. “I can’t believe this. These are like—how do you say?—home movies made here by my predecessor half a century ago.”

Toshiro stepped aside as Tucker carried the screen and projector into the ceremony room. He plopped down on a cushion, and watched her as she carefully threaded film through sprocket wheels, tested the shutter and lamp, and then placed the blank screen, discolored by age, next to the altar fifteen feet away. She clicked off the lights. She threw the switch, and the obsolete projector began to whir. There was no sound, only flickering images on the tabula rasa of the screen, slowly at first, each frame separated by spaces of white, as if the pictures were individual thoughts, complete in themselves, with no connection to the others—like his thoughts before he had his first cup of tea in the morning. Time felt suspended. But as the projector whirred on in the silent temple, the frames came faster, chasing each other, surging forward, creating a linear, continuous motion that brought a rich world to life before Toshiro’s eyes.

He realized he was watching a funeral in this very ceremony room at Anraku-ji, probably filmed around the time of the Korean War. He felt displaced, not in space but in time. On the screen, an elderly woman lay in state, surrounded by four grieving relatives and long-stemmed white chrysanthemums. A thin blanket covered her shriveled body from neck to ankles. Someone had placed a small, white handkerchief over her face, and as a young man seated beside her, perhaps her eldest son, suddenly lifted the cloth and kissed her cold forehead, Toshiro felt his own face stretch and his back shiver. The experience of ruin and abandonment that overcame him during his own parents’ funeral welled up inside him once again. In spite of himself, he surrendered to the people at this funeral his personal anguish, his pain, the powerful energy of his emotions, and this transference made the images on the screen feel so palpable that the young priest’s nose clogged with mucus and his eyes burned with tears. Yet even as he sobbed uncontrollably, he saw himself to be locked in a cycle of emotion which these fleeting, black-and- white images borrowed, intensified, and gave back to him in a magic show produced by the mind, a dreamland spun from accelerated imagery.

There was no sound, only flickering images on the tabula rasa of the screen, slowly at first, each frame separated by spaces of white, as if the pictures were individual thoughts, complete in themselves, with no connection to the others—like his thoughts before he had his first cup of tea in the morning.

After a second, he realized that this—yes, this—was what the sutras meant by kamadhatu, by the realm of illusion, by samsara. All at once, the ribbon of film in the projector broke, returning the screen to an expanse of emptiness completely untouched by the death and misery projected upon it. For these last few moments he had experienced, not the world, but the workings of his own nervous system. And this was truly all he had ever known. He himself had been supplying the grief and satisfaction all along, from within. Yet his original mind, like the screen, remained lotus flower pure and in a state of grace. At that moment, Toshiro Ogama knew. He saw clearly into his own self-nature, and lost the sense of twoness.

Outside, wind wuthered through yew trees and set chimes on the porch to ringing. Inside, the temple seemed to breathe, a gentle straining of wood on wood, then relaxation. Tucker clicked the lights on in the ceremony room. She saw tears streaming from Toshiro’s eyes, and took a step toward him. “Ogama-san? Are you all right? I didn’t know this would upset you.”

He rubbed his red eyes and stood up, self-emptied. “Neither did I. Thank you for working the projector.” She gave him a fast, curious look, and then moved to where her black leather briefcase rested in a corner. “I guess I’ll be going now.”

“Why?” asked Toshiro. “In that film, I saw how Anraku-ji once was thriving with parishioners. There was a sangha here of all sentient beings, and with no religious officials in sight. It should be that way again. Later this week I want to invite the villagers down the road to visit. Would you join my temple as its first member?”

The pilgrim did not speak, for words can be like a spider’s web. She simply bowed, pressing both brown palms together in gassho—one palm symbolizing samsara, the other nirvana—in a gesture of unity that perfectly mirrored Toshiro’s own.