We have too often and for too long seen white men with guns take the lives of young, unarmed black men and do so with seeming impunity and without accountability. We cry out: Where is justice? When will human beings be reckoned as human beings only and not profiled and pre-judged as being “dangerous” or “criminal”?

How can a young man’s death be ruled a “homicide,” and later it is determined there was no crime? How are the mothers of young black boys in this country to carry on? We cry out for justice.

Wouldn’t it be better to see young black men as the community’s future rather than its problem? Wouldn’t it be better to build schools for young black men rather than to build only more prisons to warehouse them?

Fifty years ago, I marched in nonviolent protests with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the streets of Birmingham, Alabama. We walked, in two’s, between police officers with dogs and firemen with hoses trained against us. But new laws came out of our protests, laws meant to protect us.

Some years after those demonstrations, a freedom fighter from South Africa said to me, “In the U.S. you are fortunate because, at least as black people there, you have laws on your side.” Today, that statement calls forth from me a long, deep sigh. What does it mean when we need protection from the people whose job it is to protect us?

We cry out for what seems so simple: fair and equal treatment under the law. But to view each other as “equals” is precisely the problem here. The root of this problem is the very root cause of samsara itself, namely, the over-exaggerated investment we each make in our respective “I”s.

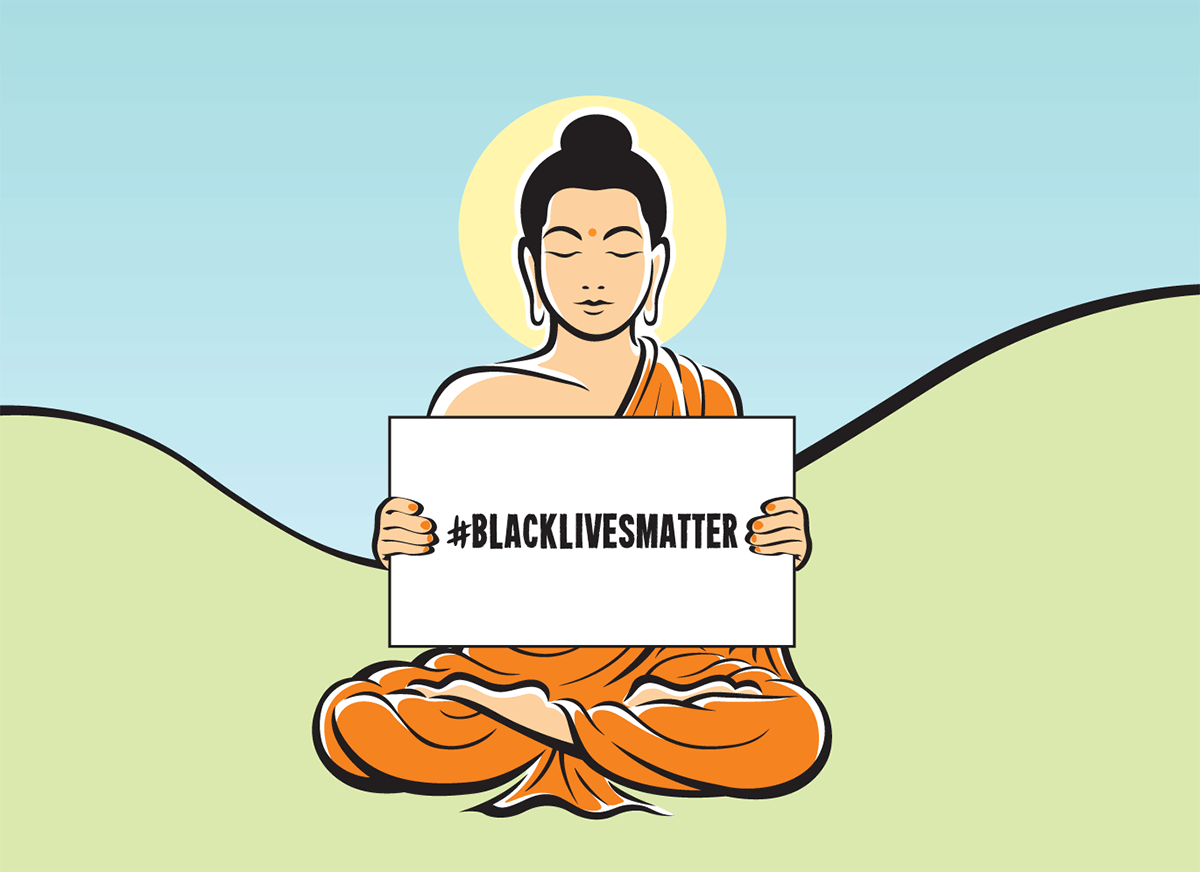

The conceit of “I” prevents us from seeing others—any others!—as “equal” to us. So some human beings actually harbor the thought that some lives matter less than others. And so we witness again—almost unimaginably in this 21st-century so-called “post-racial” society—the placards that must state the obvious: “Black Lives Matter.” I am reminded that 50 years ago the placards read poignantly, “I am somebody.” Why is this so hard for us to see and accept, and even cherish?

It seems to me that only if we harbor the deep-seated, erroneous conceit that “I am better than others” can we harbor the view that black lives—or any lives—don’t matter. This conceit is our downfall.

For many years, as a Buddhist scholar and practitioner, I have been attempting to plumb the great depths of one of the most profound and beautiful Buddhist texts of all time, the Bodhicharyavatara, sometimes translated as A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of the Life. This is the 8th-century Buddhist scholar Shanti-deva’s sonorous exploration of true compassion, or bodhichitta.

The text offers many exercises to help us to maintain and grow compassion once it has—almost miraculously—appeared. Among the many practices suggested by Shantideva, two are foremost: one can be summarized as “exchanging self with others”; the other as “equalizing self and others.”

The first exercise—“exchanging self with others”—has received the most attention. It seems so clearly to be a prime catalyst of compassion. If we can imagine ourselves as another, if we can put ourselves in their shoes, then we can at least develop empathy with another’s plight and in this way develop a wish that they not suffer. But while this may seem to be compassion, it’s really more akin to pity, offered from a position of superiority.

I think it is the second exercise—“equalizing self and others”—that is more germane to our situation today. Yet it is so very difficult to practice. For this second practice calls upon us to try to actualize our equality with others: neither our superiority nor our inferiority but our equality with them. Only this flash of insight is capable of truly liberating us.

This is the liberating view held by Dr. King and Gandhi, by the Buddha and Nelson Mandela, by Bishop Tutu and His Holiness the Dalai Lama. It is the view that we are all, ultimately, exactly the same. Not better, not worse. Human beings reckoned as human beings only. What a marvel.

If this is right, and it is something we can contemplate, then the current “racial tensions” we are experiencing (which are not “tensions” so much as calls for the recognition of basic equality) can become a signal of hope.