Jan Willis reveals why and how life is getting better for the nuns of Ladakh after the Sakyadhita conference in 1995.

Tucked away on a high plateau in the far northwest of India lies the dry and windswept region of Ladakh, one of the most beautiful and remote outposts in the Buddhist world. To the east it is bordered by the Himalayas. To the west lies war-troubled Kashmir and Pakistan. From the fifth to the fifteenth century Ladakh was an independent Tibetan kingdom and many Buddhist monasteries were established there.

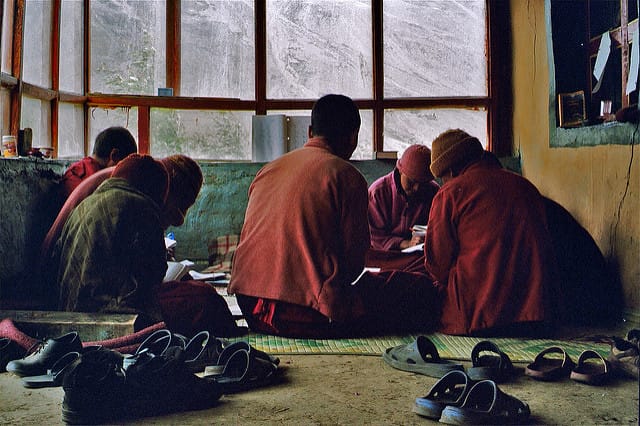

Modern-day Ladakh—whose population of 160,000 is about evenly divided between Buddhists and Muslims—is still home to many monks and nuns, but for generations nuns have held a grossly inferior position. I first travelled to Ladakh in 1995 to attend the Sakyadhita Conference of Buddhist Women held in its capital city, Leh. I was astounded by the appalling conditions of Ladakh’s nuns, who seemed to be mere helpers for the monks, with no status and no attention being paid to their spiritual path. But on a return visit in July 2003, I was able to see how the work of the Ladakh Nuns Association in the intervening eight years had made it possible for many of Ladakh’s nuns to move away from servitude and towards becoming true spiritual practitioners.

In her book, Servants of the Buddha, Anna Grimshaw chronicled a winter’s stay during the 1970’s among the nuns of Chulichan, the nunnery subsumed under the grand monastery of Rizong, which is a favorite tourist destination. Grimshaw bemoaned the sad circumstances of the nuns there, who, in her eyes, were little more than servants to the Rizong monks and didn’t receive so much as a thank you in return. When I visited Chulichan in 1995, only four of the eleven nuns Grimshaw had lived with remained. The four elderly nuns worked at growing, harvesting and preparing for sale the apricots that give the nunnery its name. They were living in the dilapidated courtyard of the nunnery—not only because it was summer when I visited but because there was not a single room in the crumbling structure without a leaking roof.

Buddhist nuns in general do not command the respect that Buddhist monks do, but the situation of nuns in Ladakh has, until quite recently, been a case unique unto itself. In a real sense, the decline in the nuns’ fortunes began with the perceptions of them held by Ladakhi monks and lay people, for in Ladakh a girl may wear the robes of a nun even though she may have taken only the five precepts prescribed for an upasika, or lay practitioner. Historically, this practice is said to have originated in the nineteenth century when a rinpoche of Rizong monastery first granted a group of young girls the right to don the robes, provided they vow to take the ten higher precepts (of novice monastics) when they reached the age of eighteen. Apparently, few of them did so. The wearing of robes was meant to be a sign that these young women were serious, but that altruistic intent clearly backfired. Since any enrobed nun encountered in Ladakh today may be “only” an upasika, no special—let alone revered—status is accorded to her at all. Instead, she is given menial jobs by her family or is hired-out to villagers or work projects with no guarantee that she will ever be free to join a spiritual community or even enjoy the free time to hear dharma teachings.

Even after the recent reforms, it is still not unusual to see a lone Ladakhi nun herding goats, tilling the fields or even working on a road gang. Road work in particular is not only labor-intensive but often dangerous as well, since roads cut through mountain passes that surge upwards of 14,000 feet. Such gruelling work allows little time for communal living or spiritual practice. In her talk at the 1995 conference, Dr. Tsering Palmo, who would go on to found the Ladakh Nuns Association the following year, spoke eloquently about the need to improve the living and studying conditions of the nuns there. Explaining the conditions that led the nuns to have so little spiritual training, Dr. Palmo said:

Due to the lack of financial support, from generation to generation, nuns in Ladakh have not been able to educate themselves. The only alternative left to them is to stay with the family and help it to earn a living. In return, the family may help the nun by supporting a retreat for one or two months of the year or by financially supporting a long pilgrimage out of Ladakh. In reality, nuns have to depend on their families for any religious activities they wish to do.

Those who manage to enter a nunnery, with great aspirations and hopes, soon have their dreams shattered by lack of proper monastic and secular educational programs. By 1994, the pious traditions of Buddhist nuns and nunneries had so far declined that they very nearly reached the point of extinction.

It is clear from my recent visit that by founding the Ladakh Nuns Association, Dr. Palmo has managed to bring a genuine nuns’ tradition back from the brink of extinction and to make dramatic improvements in the nuns’ lives and livelihoods. Accordingly, the number of nuns has tripled since 1995 to just over 900. While 790 of these women live within the three major districts of Leh, Kargil and Chang Thang, another 120 are now engaged in higher studies outside Ladakh in various locations throughout India, such as Dharamsala, Darjeeling, Mungod and Varanasi. These Ladakhi nuns have come a long way from road work.

One measure of the nuns’ progress can be seen by comparing the current situation of the Chulichan nuns with that described by Grimshaw in Servants of the Buddha. Whereas in 1995 I had seen only four elderly nuns living in the courtyard and working as farmhands, in 2003 I saw that the nunnery at Chulichan was being completely rebuilt, with a slate of new rooms being constructed with solar panels outside. The number of Chulichan nuns had now grown to twenty and most were in their mid-twenties. These new nuns no longer harvest the fields; they have a resident geshe (scholar-teacher) and time for their own spiritual practices. And all of this takes place with the blessings of the current Rizong abbot.

Within Ladakh today, the nuns’ community is growing at a strong pace while the number of monks, in fact, is decreasing. Tsering Samphel, president of the Ladakh Buddhist Association, gave three reasons for the monks’ decline. The first is that the Indian military—whose presence is felt everywhere throughout this region—has stepped up its campaign to recruit eligible young men. The second is that young men, being generally more educated, are more mobile than young females, lay or ordained. Finally, the overall Buddhist population in the area is decreasing, because, Samphel said, “Buddhists take the family-planning guidelines to heart. Our Muslim neighbors do not. Hence, we are on the verge of becoming a minority in our own country.”

One of the main factors that accounts for the rise in the number of nuns is the promise of receiving an education. Nuns and education were not related in the minds of Ladakhis in the past. In fact, almost all nuns were illiterate. (Even today, with reforms, only 20% are literate.) Without sufficient nunneries or teachers to staff them, few nuns entered communities or were instructed in the vinaya (disciplinary rules) governing their lifestyle. Those few fortunate enough to secure a place in a nunnery were still unable to gain access to qualified dharma teachers willing to invest time in them.

The 1995 Sakyadhita Conference marked a turning point in the nuns’ fortunes. It was at that point that how the nuns viewed themselves and how they were viewed by others began to change. The Ladakhi nuns in attendance were encouraged to see that there were others in the world—Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike—who were concerned about their plight. Dr. Palmo’s eloquent presentation at the conference pushed her to the forefront of the struggle to improve the living and studying conditions of the nuns, and this ultimately led her to found the Ladakh Nuns Association. Though not present at the conference, the Dalai Lama sent an inspirational letter to the attendees encouraging the nuns to persevere and to educate themselves. His Holiness’ Office in Dharamsala later made a donation to the nuns association that it ear-marked for education. And, perhaps most importantly, particularly with regard to their own self-esteem, the Ladakhi nuns democratically and unanimously decided to cast off the outmoded and derogatory Tibetan term ani by which they had formerly been known. In Tibetan, ani literally means “aunt,” but it also connotes and conjures the image of a servant. The Buddhist nuns of Ladakh decided that they wanted henceforth to be called cho-mos, “female religious practitioners”; nothing more, and nothing less!

In ancient times in India, Mahaprajapati, the Buddha’s aunt and the first Buddhist nun, declared:

I have been

mother, son, father, brother,

and grandmother.

Knowing nothing of the truth,

I journeyed on.

But I have seen the Blessed One,

and this is my last body.

I will not go

from birth to birth

again.

Her testament, recorded in the Therigatha, has become the cho-mos’ anthem.

Since 1996, Dr. Palmo’s nuns association has acted as the most inclusive umbrella organization for the overall improvement of the nuns’ situation in Ladakh. The association, working closely with the now twenty-seven nunneries in the region, has set clear priorities, including helping existing nunneries become self-reliant and self-sufficient, seeking ways to provide training opportunities in both monastic and secular education to the nuns, and renovating old nunneries and establishing new ones. The association has sponsored study tours as well as dharma teachings by eminent teachers for the nuns, and it has secured places for nuns in schools, both secular and Buddhist. It also seeks to help nuns develop skills in Tibetan medicine so they can take more responsibility for their own and others’ health care. This latter priority has grown directly out of Dr. Palmo’s own experience. She was the first Ladakhi woman to earn a degree in traditional Tibetan medicine from the Chokpori Medical College in Dharamsala.

As I witnessed—and marvelled at—the tremendous shift of energy taking place for the nuns of this remote, barren and yet breathtaking region, I couldn’t help but reflect upon the lost opportunities for former generations of nuns and for those now quite elderly nuns who had spent almost their entire lives working as the servants of various worldly masters, instead of becoming servants of the dharma. Then, as if by magic, early one morning a jeep arrived at my guest house door. I, along with three other colleagues, were being summoned to attend a special ground-breaking ceremony for the new nunnery to be run under the auspices and blessings of the renowned Thiksey Monastery.

The 500-year-old Thiksey Monastery, perched high on a hill above the Indus River roughly ten miles south of Leh, is home to 120 monks. Because it also houses one of the largest statues of Maitreya, the future Buddha, whose form rises majestically through two storys of its main gompa, Thiksey is on every foreign visitor’s must-see list. At Thiksey, Khenpo Nawang Jamyang Chamba and a gentle and unassuming geshe named Tsultrim Tharchin have taken His Holiness’s words to heart and become nuns’ activists. The rinpoche spearheaded a drive to have his monastery donate the land for the nunnery; Geshe Tharchin has been offering classes in the Thiksey village town-hall in reading, writing and ritual skills for the past two years to the twenty-six Thiksey-area nuns. The youngest of these nuns is forty-three; the oldest eighty-seven. Though enrobed, most of the nuns have never lived together with any other nuns. Instead, they have spent thirty to fifty years working on road construction. Geshe-la’s classes are the first they have ever had.

The jeep raced past the imposing Thiksey buildings and continued on a few miles south. It then turned off at a sign that declared the entrance to Nyerma. Nyerma is dotted by melted-away stupas designed by none other than Rinchen Zangpo himself, the celebrated tenth-century Tibetan translator and redactor of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. This land was the site of Zangpo’s very first monastic seat; it will now become the site of Thiksey’s first-ever nunnery and home for these twenty-six nuns and a few others.

The nuns gathered here—aged and wrinkled, the years of hard labor showing on their faces—were wearing their robes and beaming. Even as they chanted with all the soft sweetness of their mature voices, most dreamt of the time when they would feel educated, practiced and hence qualified enough to take the vows of higher ordination. For them, Thiksey Nunnery will become the place where they can devote themselves to their spiritual practices, where they can study and truly become cho-mos.

Of Ladakh’s 900 enrobed women, these twenty-six will—in a few years—have a place for their communal life of spiritual practice. For other young girls and women, there is only hopeful waiting. At present, just over 500 nuns actually reside in such communities and some of these communities carry on in spite of less than ideal living conditions. Roughly 250 nuns are enrobed in Ladakh but are still forced to live on their own and to practice in whatever free time they can manage to secure. Many positive changes have occurred for some of the nuns in a relatively short period of time. In this respect, one can say that Ladakh’s cho-mos, are on the rise. But they were coming from a pretty low place. If Buddhism is to remain and flourish in this region so close to the sky, and to sustain and strengthen its followers, much more work remains to be done.