I used to stare at the meditating Buddha in our living room: his straightbacked posture, his wide shoulders and narrow waist, his elegant hands resting humbly in his lap. This statue sat on a shelf seven feet high. Around him were other Buddhas, two yellow candles, and a cup of rice to hold incense sticks. He could rest comfortably in my palm and weighed no more than a couple of pounds. Yet he was heavy in spiritual weight, my father always said.

The Buddha, like my mother and father, was not native to America. He had been in my family for years, ever since my father was a barefoot boy running wildly in Ayutthaya, Thailand. I wondered if the Buddha, too, felt misplaced in this new world—a world without the heat and humidity of his native home, without the familiar sounds of geckos and mynahs and the evening song of croaking frogs. This was America. This was Illinois. This was Chicago. Here, the house shook on Mondays when the garbage truck rumbled by. Here, our neighbor Jack rode endless loops on his riding lawn mower.

My family revolved around the Buddha. Each morning, before I went to school, I prayed to him. Some days, my mother allowed me to stand on a dining-room chair to offer him a shot glass of coffee—cream, no sugar. Other days, she let me light the candles and incense before we prayed. I was supposed to close my eyes and think only good thoughts, but my eyes remained open, fixed on the Buddha. I imagined that, at any moment, he would rise and float down like an autumn leaf. I imagined he would impart vital secrets, and I could ask him the questions that plagued me. There, in the living room, he would walk onto the palms of my hands and we would spend the evening—boy and Buddha—speaking like friends.

“The Buddha is with you,” my mother used to say. “Believe in him.”

Buddha was the holder of my secrets. He understood that loneliness and emptiness were one and the same.

And so I believed that the Buddha was more than a bronze statue, that he was solid like a body is solid—the way it gives a bit when you lean against it, the way it molds to accept the presence of another. He possessed the gift of language and was bilingual like me, skipping freely between English and Thai. We spoke often, our conversations in hushed whispers, and he sounded soothing, not harsh like my elementary school principal or gargled like the monks at temple. Buddha was the holder of my secrets. He understood that loneliness and emptiness were one and the same.

Once, when I was in the living room, my mother asked from the kitchen who I was talking to.

“Buddha,” I told her.

“Excellent,” she said. “Speak to him every day, okay?”

Mrs. Slusarchak, my second grade teacher, asked my mother to come for a meeting one afternoon.

A patient teacher, Mrs. S lived in Munster, Indiana. “I live in Munster,” she always said, “like the stinky cheese.” But I thought she was saying Monster, and imagined hairy demons living in cheese-shaped houses. I liked her. She wore bright dresses—Hawaiian pastels—that seemed to ward off the dreary Chicago winter days. She looked pretty with her short hair and small glasses and laughed with her whole body, which was shocking but funny.

The day of the meeting, my mother came straight from work, still in her nurse’s uniform. She smiled timidly, her purse in her lap, and sat across from Mrs. S. I was next to my mother, but I aimed my eyes out the window at the swing set.

Mrs. S said that I was a math champ every week and that my penmanship was the best in the class. My mother patted my head and said, “We practice every day.”

“I can tell,” Mrs. S said, then let out a laugh that nearly knocked my mother off the chair. “But I’m concerned about his behavior.”

“Has he been bad?” my mother said. “I will tell him to be better.” Mrs. S shook her head. “Not in the least. He’s just terribly shy.”

She went on to talk about what had happened at recess. How I’d wanted to get on the swing but Tommy W told me to go away, so I did and sat on the bench, staring at my hands. This was what I did often, she said. Stare at my hands. I could never meet her eyes. I could never speak more than two words at a time. “There are days,” she said, “that I don’t hear a word from him.”

“Is this true?” my mother asked me in Thai.

I stared at my hands and my mother sighed. It was a sigh that said she knew exactly what Mrs. S was talking about. “I’m sorry for him,” she said. “He is like me.” She, too, had a fear that gripped her. It made her hide in her room, reading magazines and sewing endless dresses she would never wear.

Mrs. S nodded. She understood. She suggested my mother enroll me in Cub Scouts or other activities, so that I would be encouraged to meet some friends. My mother agreed, and the next day she sent me to school with a bagful of apples for my teacher.

But what I wanted to say was that I had a friend: Buddha, and within him was a heart that beat strong and that awakened something in me.

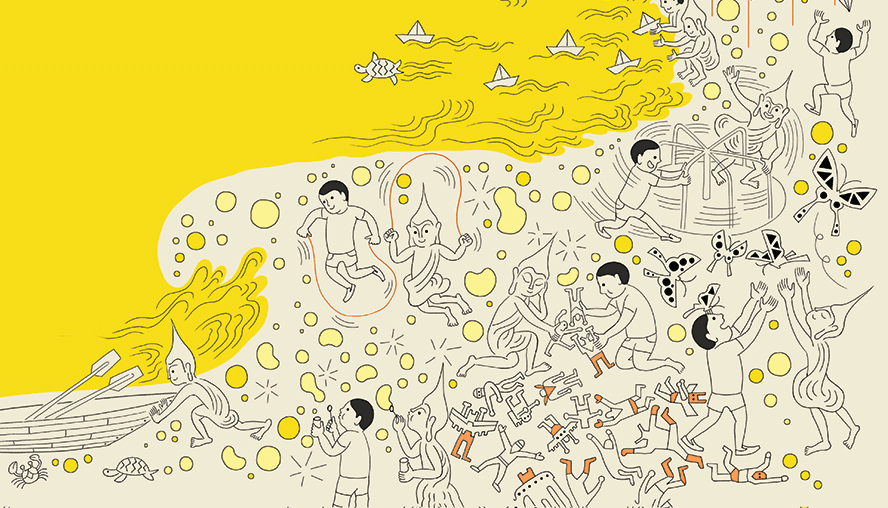

This was not a spiritual awakening—not a recognition beyond the self as many theologians would define it. Nor was it a sudden epiphany to a transcendent crisis. I was too young to comprehend such lofty ideas, too young to fully understand what Buddhism was or why my family was so devoted to it. I was being awakened in the way a newborn registers it has fingers and toes, and those fingers and toes have function. I was being awakened in the same way you realize that if you see one bird, you might see another and another. You realize that you are not as alone as you thought you were. The world is filled with birds, or in this case, with buddhas, and every buddha is a friend.

“I spoke to him every day,” my friend told me. “His name was Bob.” My friend and I were in our early twenties, and in the best place to be on a hot summer evening in Chicago—an over-air-conditioned bar. He was relaying tales of the imaginary friend he had when he lived clear across the ocean, growing up in a semi-affluent family in Poland.

“What did you two talk about?” I asked.

“Bob was well-versed in all subjects.”

We laughed. “Do you remember when he started appearing?” I said.

“About the time when my mom was about to ditch my dad and come here.”

“You think that’s why Bob appeared?” Imaginary friends, I’d discovered through research, often materialize during stressful moments in a child’s life. It is how the child grasps and copes with the turmoil of his or her situation.

My friend shrugged and seemed to speak more to his drink than to me. “I remember what Bob looked like, though.” Then he went on to describe Bob, who had crazy wild hair that went in all directions and who always appeared barefoot and in a blue-and-white-striped sweater and khaki shorts. “Isn’t that crazy?” he said.

I shook my head.

“What’s crazier,” said my friend, “is that I thought I saw him the other day. At work.”

“An older Bob or young Bob?

“The same Bob.”

“Was he barefoot?” I asked.

“Can’t be barefoot in Home Depot. But he had on the same sweater and he was holding hands with his dad.”

“Are you sure it was Bob?” I asked.

“Nope.” My friend ordered another drink. “When you talk about imaginary friends, you really can’t be sure of anything.”

Maybe I can’t be sure of Buddha. But I am sure that when I was seven I was picked on and bullied. I am sure that I was born an only child and spent much of my time by myself. I am sure that I am the son of two immigrant parents who loved me with all their being, even more than they loved each other, and sometimes, because of this love, they smothered me with suffocating affection. I am sure that my family was scared and they, too, turned to Buddha for day-to-day guidance through this world that was not Thailand, where it snowed when there should have been hot, devouring sun. I am sure that I possessed an overactive imagination. I am sure that when I felt overwhelmed, I hid myself within the darkness of my arms and made the world sound hollow like a cave. I am sure that the safest place in the world when I was small was the back of my mother’s knees. I am sure that the mind is a mysterious muscle, and the mind of a child is even more mysterious.

And of this I am positive: every time I looked at the Buddha in the living room, I found myself calm, serene, as if caught in a moment before waking or sleeping.

Before I went to sleep, I talked to Buddha. My parents were trying to reclaim their bedroom. Up until then, I’d wedged myself between them on their handmade bed. I was a husky boy and prone to tossing and turning. When I was three or four, this was fine, but now I possessed a larger body that took up more of the bed, and my father was tired of having my hand slapping his face.

At night my new room scared me, even though my mother and father had painted it the light shade of green I’d asked for, and even though I’d been in it countless times during the day. Darkness changed the landscape of the room. There was an absence of color, and that absence felt oppressive. The only furniture was a twin bed and a metal desk, and there was nothing on the walls, except for a small Buddha pendant hanging above the bed and a picture of my father when he was a monk. Although it was only half the size of my parents’, my room seemed too big, sonorous. I felt there were places for monsters to hide, especially in the closet, and I convinced myself there were things that existed in there. Unpleasant things.

At night, Buddha eased me to sleep with his wild stories. “One time,” he’d begin, and the tale would take off in bizarre and outrageous directions, always ending with a hero who stood tall and was not afraid to take on the world. We played rock, paper, scissors, and Buddha was always shocked when I beat him.

I frequently ended up back in my parents’ bed until my father put his foot down. “Big boys sleep in their own rooms,” he said.

“You are a big boy, yes?”

I nodded.

“Nothing can hurt you,” he said. “Buddha protects us.”

And he did. He sat cross-legged on my bed, not in a meditating fashion, but how I sat when Mrs. S read to us. My Buddha did not speak sage advice. He adopted schoolyard lingo, and told me the kids at school were dork noses and that I was much better than they were. At night, Buddha eased me to sleep with his wild stories. “One time,” he’d begin, and the tale would take off in bizarre and outrageous directions, always ending with a hero who stood tall and was not afraid to take on the world. We played rock, paper, scissors, and Buddha was always shocked when I beat him. Then when the darkest part of the night came, he hovered above me and I could feel the heat of his presence. His skin glowed, like a night-light.

One day imaginary friends are there and the next they are not. This is true of real friends, also. The friends we had when we were in school—what happened to them? Jody is now a photographer in North Carolina. Casey works for USAA in Texas. Andrea is a schoolteacher in Illinois. What we share is a past, a period in time. We become a memory. We become part of a sentence that begins with, “Remember Ira…”

But seldom do we remember our imagined friends, because to admit to them is to somehow admit to a deficiency on our part. Yet they existed, too. They were essential. But now we want to keep our friends a secret—to protect them from ridicule, from sideway glances. They protected us when we were younger, and now it’s our turn to protect them.

“Remember Buddha?” I want to say. “Dude told the craziest stories.”

Before Buddha became Buddha, he was a boy. He was Prince Siddhartha, heir to his father’s throne, groomed to be the greatest king to ever live. This was the pressure he lived with day in, day out. I imagine this to be stifling, every limb weighed down with lead. I imagine that even Siddhartha, a boy destined for greatness, might crumble under that pressure. And the king sensed it too. He feared his son would leave the palace, so he built other palaces within the palace; there would be no need for Siddhartha to leave. But what does a boy do without others around him?

I wondered about this.

As soon as I learned how to read, my mother gave me a book entitled The Story of Buddha. It was published by a press in New Delhi in 1978 and had pictures on every other page. What I remember most about the book were the times Siddhartha spent alone, something that displeased his father. The king bemoaned his son’s lack of interest in his education as a king. He complained how Siddhartha would rather be alone in the garden than with his teachers. But was he alone? Did he speak to the butterflies, the birds, the critters that scampered around in green? Could Siddhartha, who possessed an extraordinary mind, have imagined someone in that garden with him, someone to assuage his loneliness?

Possibly.

Later, when Siddhartha became Buddha, he would teach us that nothing is ever truly alone; everything is in relation to everything else.

God is in everything. He is everywhere. He is always with you. Sitting with my wife’s family at their Presbyterian church, I often hear these words, which are not dissimilar to the ones I heard when I was a boy sitting in temple listening to a monk’s sermon. Buddha is with you. Keep him in your mind and heart. We look to these spiritual guides for ways to calm our tumultuous lives. There is comfort in the notion that we are never alone, that we are connected by an invisible thread to everything else in the world, the seen and the unseen.

Buddha remained unseen when I traveled down the stairs in a laundry basket, one of my favorite games. But he was there, sitting with me. He remained unseen when we wrestled with body pillows. But he was there, with a pulverizing elbow. He remained unseen when I played with my action figures. But he was there, making my GI Joes move in combative maneuvers. He remained unseen when I played football outside. But he was there, my wide receiver, catching passes for touchdowns.

My Buddha was a mix of wisdom and mischief. He was my friend, after all, and as friends we were on equal ground.

The real Buddha would not do such things. The real Buddha would have preached peace and emphasized the life of the mind. But my Buddha was a mix of wisdom and mischief. He was my friend, after all, and as friends we were on equal ground.

This friendship, this very idea of Buddha, made me change, if only a little. It made me yearn for real companionship, and perhaps that was the reason I fought against my shyness. If I could speak to Buddha, why couldn’t I speak to the weird boy with the spiked hair who looked just as lonely as I was? Or the other boy with the golden hair and thick glasses? Or the other boy who was as gangly as a bean? Perhaps they had imaginary friends, too, and in this we shared something. Perhaps our imaginary friends would not be needed anymore, and they would simply disappear.

At what moment my imaginary friend disappeared, I don’t remember. But he did, and so did the Buddha on the shelf one evening when I was a teenager. Then there was a new Buddha, a green one made of jade and covered in sparkling gold robes. This new Buddha was beautiful the way something new is beautiful, but I found myself looking for the familiar tarnish, the layer of dust that blanketed the old Buddha. The old Buddha went when my father went; it was his, after all, and was one of the only things he took with him after the divorce.

I missed that old Buddha, my friend— missed his presence, his watchful gaze on the shelf. There were questions I still wanted to ask, guidance I still sought. I wonder what the view is like where he is now, and does he remember the boy who used to talk to him? He sat there for fifteen years of my life, and though Buddha has become Buddha again and not my play pal, he is never far from my mind. All I have to do is close my eyes to see him: his straight-backed posture, his wide shoulders and narrow waist, his elegant hands resting humbly in his lap.