There was a knock at the door of my cabin. There he was, the guy I was here with at this music festival.

“I locked myself out of my cabin, so can I use your key to get back in?” he asked. I looked at him, wondering how this grown man makes it through life. “No, you can’t,” I said slowly. “Why?” he asked, confused. “Because that’s not how keys work,” I said, gritting my teeth. “My key won’t open your door.”

He looked at me helplessly, just as he had when he couldn’t figure out how to get the car key out of the ignition, and I had to tell him to put the car in “park” when he parks it. Like when he forgot his festival pass and we were forty minutes away, and when he accidentally ran over a raccoon and joked about it constantly, even though I told him it upset me. He was baffled when I couldn’t wait to drop him off at the airport after four very long days.

Dating is an area where I see a lot of suffering, especially in the wacky world of online dating.

Man oh man, dating is an area where I see (and experience) a lot of suffering, especially in the wacky world of online dating. Every day my phone lights up with a friend asking for help analyzing a message (or the lack of a message). It’s not exclusive to gender or age or any other qualifier—everyone’s doing it, everyone’s messed up from it, and we all think, “It must just be me.”

It’s not. We’re all floundering in these murky dating waters together, telling ourselves the same stories about why we (and everyone else out there) suck. So I decided to ask some Buddhist teachers to throw us a few lines of wisdom back to shore—for those times when there’s no “why” or “how” and our insecurities fill in any gaps with self-constructed storylines about how inadequate we are.

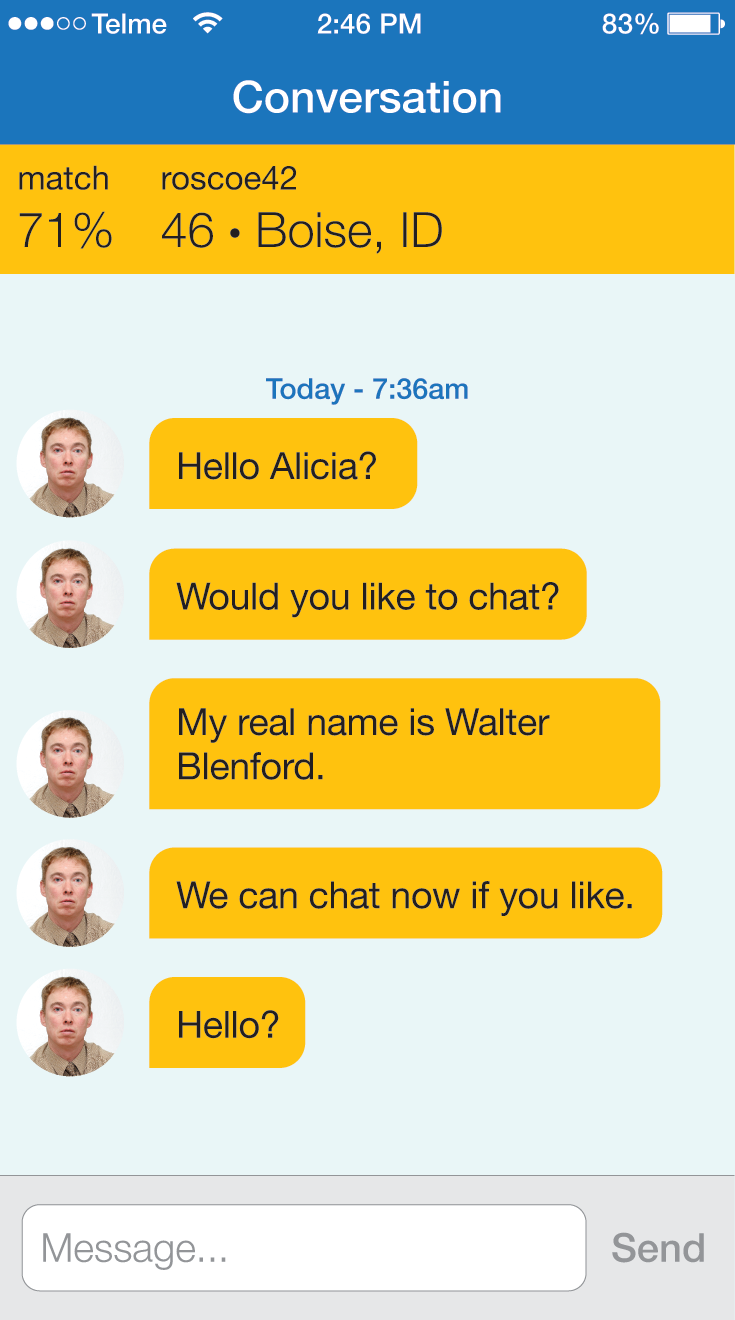

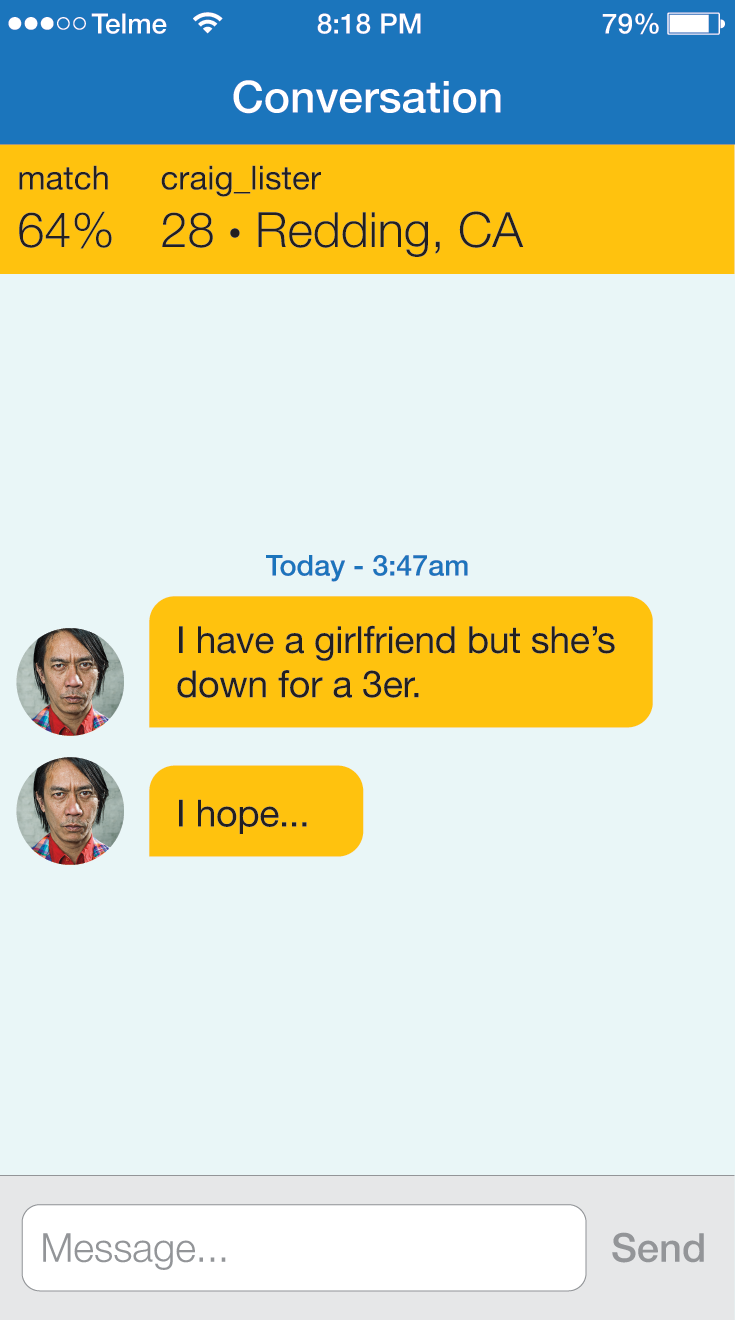

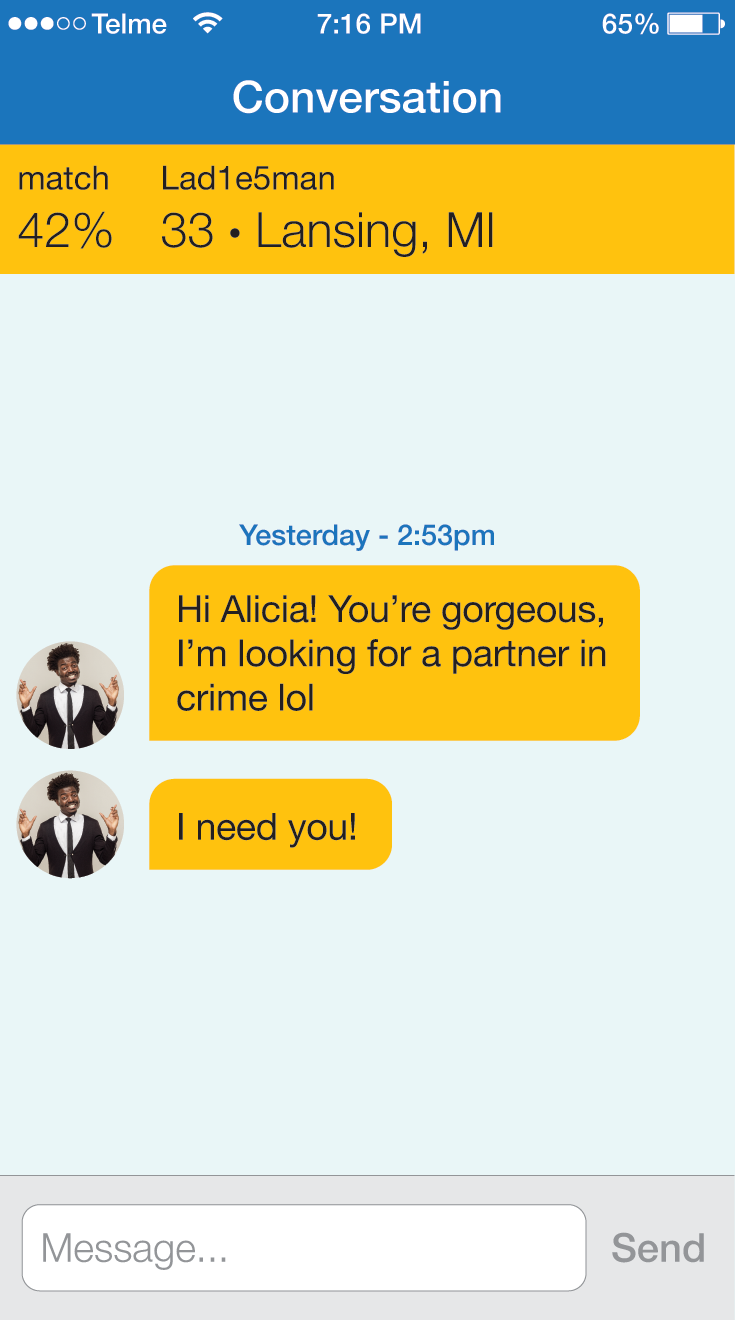

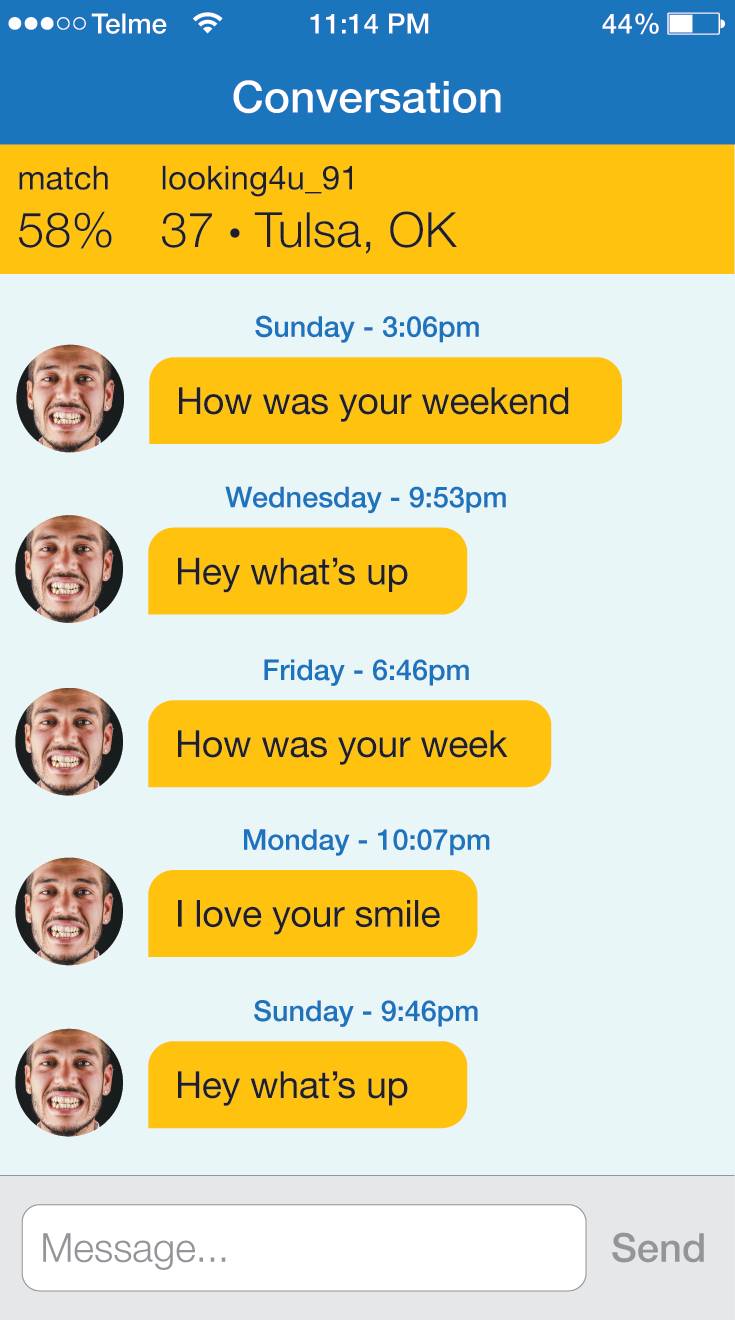

Then my friend Alicia, upon hearing I was doing this story, announced, “I’ll do it. I’ll sign up for a dating site and we can document my process from the very beginning. It’s investigative research, so I’m not attached to any outcome. It’ll just be an experiment.”

I had my protagonist. Now we needed some dharma guidance to light our way through this journey. I found it in Buddhist author Yael Shy and Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist Melvin Escobar. “What a gift and what a risk,” said Escobar about Alicia’s volunteering. “Thank you for your service and practice.”

Getting Out There

Four friends gathered to help Alicia create her dating profile. I helped her write her description, using the same guidelines I’ve used to write my own. Here’s the thing: no one knows what the heck to put in these darn profiles. Some people make a wish list: “I hope you’re into hiking, love dogs, and won’t eat all the chocolate out of the Neapolitan ice cream.” Others post a laundry list of qualities they don’t want: “No drama. No head games. No people who wear blue socks on Tuesdays.”

I always imagine the online dating world to be like a party we’re all attending, so I try to present the version of me you’d meet at a real-life party—a little redhead whose teeth are blue from red wine, who is probably trying to eat all of the smoked cheese, and who may or may not be wearing a large knitted sweater called her “adventure sweater.” I also read others’ profiles as if I’m at a party as well. Can you imagine if you walked up to someone by the buffet table and said, “Hi, how are you?” and that person replied, “NO DRAMA!! NO HEADGAMES!!” You would scramble for safety. So we wrote Alicia’s profile to present her “party person.”

Alicia said at that moment everything seemed to be flourishing in her life. “I’m very open, grounded, and rooted in who I am,” she noted. “My friendships are getting deep and rich, I’m speaking out more at my job, and I’m also creating better boundaries. So why not try this now?”

Alicia hadn’t been dating for awhile, because the last time she tried it, it was for the wrong reasons. “I acted out of, ‘Everyone around me is in a relationship. I need to get one.’ It was from a place of fear.” Who Alicia chose to meet reflected this. “One guy told me he was a spy with the government,” she laughed. “When I started to poke holes in his story, he said, ‘Oh, this isn’t working out.’”

Alicia also met someone who was racist and anti-immigrant. “So I said to him, ‘I am a woman of color and an immigrant.’ And he replied, ‘Oh, but you’re a good one.’ I’m like, ‘No, there’s no such thing. This is it.’ Then I took down my profile. I was done.”

Another reason Alicia decided to give dating another try was that she now had our group of friends to support her: “Talking to all of you about it takes the taboo and shame out of it. Plus we usually only hear about the disastrous or dream-come-true experiences. We need to hear about in-between experiences.”

For the initial stage of online dating, our mentors had this advice to offer Alicia.

“You’re going to need the three jewels handy,” advises Melvin Escobar. “Remembering our buddhanature and the buddhanature of others, along with the teachings and the community, is essential for online dating. Our friends often know us differently than we know ourselves. It’s an important practice to enlist friends and community for support.”

Escobar also warns that “no matter how perfect your profile is, you will not be satisfied. According to the teaching of no-self, the self is really an interdependent product of interlocking causes and conditions that exist in a complicated web. It is unskillful to be attached to fixed identities, and yet dating sites run on making matches between implicitly fixed aspects of our identities.”

As a person of color himself, Escobar offers this insight to Alicia: “A significant part of this society’s karma is racism and the other ‘isms.’ As a woman of color dating online, you will inevitably encounter this source of dukkha, suffering, in its many forms, including rejection and exotification. Some say that no-self is the ultimate remedy for the ‘isms,’ but to use the dharma in this way can be an expression of spiritual bypass.”

Yael Shy offers this advice:

“Dating is an athletic event of the heart. Athletes stretch before they start playing. Dating requires the same amount of warm-up. First, assess the situation. Alicia took the temperature of her own heart and checked to see what her intentions were before beginning to date. Check in with yourself—how are you feeling? What emotions are present? Are you excited, full of desire, openhearted, exhausted, depleted, angry? Knowing where you are helps you become aware of what you are bringing into your interactions with others.

“Second, take a moment to name your desire. What do you want from online dating? Not ‘What does the magical, spiritual me who has no needs and no attachments want?’ What does the real-life me want? To be seen? To be wholeheartedly accepted? To find a wife/husband? To have fun? To have good sex? No judgements on what the desire is, just try and name it, visualize it, and accept it for yourself.

“Third, set an intention. It can be simple and short, but it should help to guide you. When I was online dating, I would set my intention (whenever I remembered) to be truly honest, to show up as my full self, to remember my own lovability, and to trust my gut.”

Swiping

It was now time to swipe for matches—left for “no” and right for “yes.” We friends oohed at some profiles, and to make the others laugh I read some aloud as if we were at a party. But Alicia didn’t laugh, and as she swiped, she narrated her thoughts. “How can you decide if this is someone you’re into, based on a picture?” she asked. “There might be people who aren’t photogenic who have amazing personalities and they get rejected, or people who capitalize on their good looks and don’t have good intentions. These are people with hearts, who are just as lost as me.” Then Alicia thought for a minute. “I mean, there could be some serial killers in there too.”

Alicia found she could only swipe for a few minutes at a time. “I find the act of swiping left on another human being disturbing and sad. I keep thinking, ‘I hope you find love. I hope you find whatever you’re looking for.’ It’s all so artificial and it both heightens your sense of ego and gives you anxiety that maybe this match could be your soulmate.”

Her perspective made the rest of us stop laughing too. “Geez, most of us out there are swiping away when Netflix gets boring or we’re on the toilet,” one person said. “And here you are setting aside time to do this consciously and mindfully.”

So I asked our mentors, “How do you ‘mindfully swipe?’”

Yael Shy offers these words: “Not every person is for every person. It’s okay to feel weird about something someone puts in a profile, or a picture they took, and decide to swipe left. Trust that someone else will find them who is excited about their electronic music obsession or their strangely-shaped head.

Feel free to move slowly and keep checking in with your heart.

“At the same time, the online dating medium is imperfect. It’s hard to get a read on people before you meet them in person, and snap judgements can often be wrong. It’s easy to layer projections on someone (good and bad) from a photo or a simple profile. At this early stage, successful dating is about walking the line between trusting your gut—and your sense of attraction to others—and overjudging or over-projecting onto them. Feel free to move slowly and keep checking in with your heart.”

“Notice when you’re inventing fantasies about others,” advises Melvin Escobar. “What are the underlying feelings? Is craving arising? Is comparing mind happening? You might also connect to the energies of your heart and to the hearts of others and wish them well as you swipe left.

“It’s okay to mix some humor into your loving-kindness for them: ‘May you be safe and protected.’ ‘May all beings be free from bad lighting and the causes of bad lighting.’ ‘May you not be attached to the way you looked ten years ago.’ ‘May I not get caught up in self-delusion.’ ‘May the person you cropped out of your profile pic be happy.’ ‘May I find peace in an uncertain world.’ ‘May your good looks take you far in life.’ ‘May you love yourself just as you are.’ ‘May I love myself just as I am.’”

Escobar says we can also use equanimity practice here: “Use phrases like: ‘I feel your pain, but I’m not responsible for your pain.’”

Matches

Alicia selected five matches and began chatting. But something surprising happened as she did—she began to meet herself in ways she didn’t expect. “I suddenly started to think, ‘What’s wrong with me that I have to look online for love? Why can’t I just go see someone across the coffee shop and that’s it?’ Then I reminded myself that no one talks in coffee shops anymore, and this is the way the world works now.”

Well…sometimes. Alicia started chatting one night with someone we’ll call “Mark.” The next morning at her local coffee shop, she happened to spot…you guessed it…Mark. “We chatted, we messaged later that we thought each other was cute, and we planned a date,” she says. But the night before the date, Alicia’s sense of who she was took some major turns.

“At first, I felt confident,” she says. “Then my old insecurity appeared and said, ‘Someone thinks I’m cute. Really?’” Once her insecurities got a voice, Alicia suddenly saw it was because she had… gulp… hope that this would turn into something. “I started to panic because, oh no, this could be something. It’s so serendipitous.” Alicia’s next statement sums up pretty much every human’s fear in such a situation: “Fuuuuuck. I could get hurt. I have to show up—like, the real me. I could like this person. This person could like me. Fuuuuuck.”

Alicia had convinced herself that she had been single for so long that her life was complete and she didn’t need anyone. “But that was an illusion,” she says. Alicia realized although she was trying to be mindful of the emotions of others, she was not allowing herself to have emotions. “I was telling myself, ‘I’m like a scientist doing an experiment.’”

Alicia discovered she was using Buddhism and mindfulness as form of spiritual bypass. “I was trying to go into this from what I thought was a spiritual perspective. Then the facade crumbled and now I’m in a real spiritual situation, because it’s pretty damn groundless now.” While she had been trying not to get caught up in stories of who the others were, “I got caught up in my own story of being a Buddhist.”

I want to be in love, but I don’t want to hope.

Trying to understand the role of hope was Alicia’s real challenge. “There’s this idea that hope is suffering. Hope is pain. I want to be in love, but I don’t want to hope.” What followed these thoughts was a spectacular meltdown. “It was one of my favorite meltdowns I’ve had recently,” Alicia says. “You’re really mourning the pieces of you falling off that don’t serve you anymore.” This was Alicia’s tearful goodbye to the persona she had unknowingly layered on to protect herself.

I asked our mentors to advise us about the concept of “hope”:

“Hope doesn’t need to be abandoned, but it is unskillful when it takes the form of attachment,” says Melvin Escobar. “We can bring mindful attention to feelings of hope. Notice how it shows up in the body. Notice the leaning forward, the tensions that arise, the rush of feel-good hormones. Notice how it shows up in ‘either-or’ thinking: ‘This could be the one!’ or ‘This isn’t the one!’ We are practicing mindfulness when we notice these sensations of the body-heart-mind and come back with kindness to things as they are. Acting in alignment with wholesome intention, rather than with an attachment to how things will turn out, is a skillful way to practice with hope.”

Yael Shy says that Buddhists, and everyone else, should let themselves feel hope and excitement, if that’s what’s coming up. “Just like Alicia, I used to try and squash my hope as soon as it appeared, worried that it might make me too attached to outcomes I couldn’t control that would leave me hurting when it all came crashing down,” she says. “‘Don’t get your hopes up’ was my mantra. I thought this made me a good Buddhist.

“The sad part of that mantra, however, was that it never worked. My hopes somehow always still managed to get up, and if things fell apart, I always got hurt. No amount of pre-work telling myself otherwise could protect me. The only thing it did was make me anxious and miserable in the lead-up to the date.

“Buddhism isn’t about abandoning our desire or excitement. It is about becoming aware of our desire, as Alicia did. Naming it. Feeling it. Opening up to it. For me, every opening to desire comes with a measure of fear. What if everything falls apart? What if I get hurt? Yes, I gently say to myself, that might happen. But it will inevitably happen if I never take the risk in the first place. Telling myself not to get my hopes up just doesn’t work. Instead, can I open up to love and hope in the face of tremendous risk? If my heart breaks, I can say that at least I had the joy and excitement in the lead-up.”

Alicia made plans to go on her date with Mark, making a point to allow hope to be present while realizing she couldn’t plan for a particular outcome. “This is not what I thought I was signing up for,” said Alicia. “But I guess affairs of the heart do require your heart.”

In our next issue, follow Alicia’s journey as she navigates meeting her matches face-to-face, with advice from our Buddhist relationship experts for each step.