When tantra touched down in America half a century ago, Westerners tended to view it as an exotic brand of Buddhism built on impenetrable esoteric doctrines. Western writing still often portrays the tradition inaccurately, perpetuating myths and misunderstandings.

Buddhist tantra, or Vajrayana (“the indestructible vehicle”), is one of the three major forms of Buddhism, along with the Theravada and the Mahayana, to have developed in India. While the Theravada spread south through much of Southeast Asia, the Mahayana and Vajrayana traveled north to Tibet, Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan. As a result of the Tibetan diaspora and lamas’ open-handedness in teaching, there are now many Western Tibetan Buddhists who practice Vajrayana.

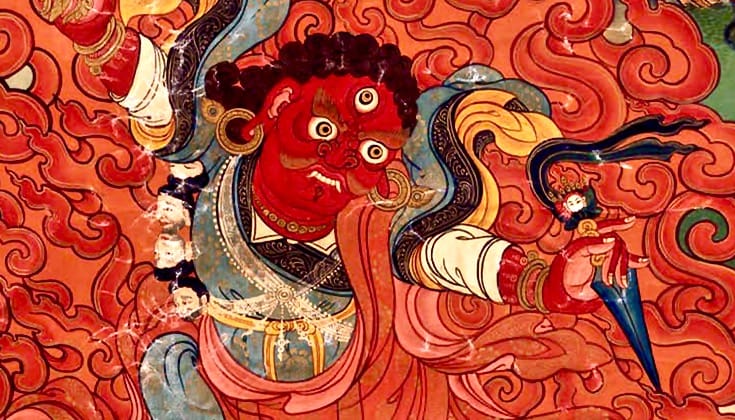

The Vajrayana is essentially a Mahayana tradition and therefore emphasizes the ideal of the bodhisattva, the buddhanature within all beings, and the practice of universal compassion to relieve suffering. Over its history, however, several features have distinguished the Vajrayana from the more conventional Mahayana traditions. For one thing, the Vajrayana has been intensely practice-oriented, and it declares that full realization is possible within this lifetime through meditation. The distinctive meditation methods of the Vajrayana include lineages of formless meditation (Mahamudra and Dzogchen) and intricate rituals. These include visualizations of male and female buddhas, the repetition of mantras, the making of elaborate offerings, and finally the practice of various forms of yoga that deal with the subtle or energetic body. Although these colorful and dramatic forms may seem rather different from those of apparently more simple and sober types of Buddhism, the Vajrayana pursues the same goal and the same realization as the other forms of the dharma: shedding of the illusions of a separate, solid self so that life may be unleashed in all its sacredness and splendor.

Although the goal pursued by the various Buddhist traditions may be the same, the ways they talk about that goal reveal important differences. While the Theravada chooses to speak of “cessation,” the abatement of ego activity, and the Mahayana of “emptiness,” the absence of any substantial or enduring essence to self or world, the Vajrayana talks about the goal in terms of the phenomenal world, the relative experiences that make up our lives. According to the Vajrayana, realization is not attained by turning away from the world of appearance toward some other realm. Instead, through the practice, we are to dismantle our attachment to what we experience. When we do, we see the seamless enlightenment that always was and always will be―the world is an immense, ineffable, sacred display, charged with incandescent intensity of being and universal liberating wisdom; and we ourselves are buddhas―expressions of the awakened state in human form. This tantric realization is so immense and joyful, and it is so unconditionally life affirming, that its only possible expression is love for all that is―mahakaruna, or great compassion, in Buddhist terms.

Cultures, including Buddhist ones, have historically tended to ambivalence toward spiritual realizations of this magnitude because they lead the realized to love in ways that may transcend or destabilize the status quo. In India, tantric saints were often persecuted; in Tibet they were frequently criticized or even driven out of the monasteries. More recently, in the West, scholars have denigrated the “crazy wisdom” of tantric saints as an excuse to call into question the legitimacy of the entire tantric tradition. A tiny percentage of truly realized saints in the tantric tradition, as in virtually every other religion, sometimes behaved in unconventional ways to express a love for others and a desire to free them that knew no bounds. What a shame that the Western world, both in academia and the popular press, has sometimes attempted to portray tantra in salacious or derogatory terms, and to deny the depth of its spirituality.

The following discussion is an exploration of this colorful, evocative, and to some extent unfamiliar expression of the dharma and the fascinating process by which it has been seeking to have its voice heard in the modern world―a world that in many respects thirsts for the richness and intensity of awakened experience that the Vajrayana offers, but which is also unabashedly fearful because of the loss of ego or “self” that tantric practices lead to.

Buddhadharma: Early writings on Buddhist tantra in the West described it almost as a freakish aberration. We’ve come a long way from those days. Nevertheless, tantra is by its very nature exotic and esoteric, so it can cause puzzlement or even disdain. How do you think tantra, Vajrayana, is perceived today?

Anne Carolyn Klein: In the world I’m most familiar with, academia, there’s a lot of interest in tantra. There’s interest in assimilating it to other themes in religious studies. For example, because of its investigation of mind states it becomes associated with different kinds of Western psychological analysis. It is also associated with “the transgressive,” the encouragement to transgress certain societal norms. Transgressive is about going against what people think is correct, about being a little bit “in your face.”

But while scholars like to talk about tantra as transgressive, in my view that misses how tantra actually functions for its Buddhist practitioners. It kind of skews the conversation into alleys and byways that don’t really take into account the long history of how tantric ideas and practices have been assimilated very gradually and very thoughtfully—first in India, but particularly in Tibet—into an organized, graded path that leads to the very same realization that is central to all of Buddhism. Vajrayana is not predicated purely upon being radical and iconoclastic.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: Absolutely. The details of what Vajrayana means and how it works will come across in time as we begin to share more and see more teachers. It would be difficult to clarify everything in a short period of time. Many great Vajrayana masters traveled to America, such as His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa, His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, the venerable Kalu Rinpoche, His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche. The very venerable Trungpa Rinpoche took North America as his seat and set a very good ground. Nevertheless, we can see how acculturating people to tantra is necessarily a long process.

Buddhadharma: Practicing tantra requires a strong community context and careful training. How are we doing in creating Vajrayana communities in a context that’s pretty different from the one in which Vajrayana flourished for a thousand years?

Anne Carolyn Klein: People become attracted to Vajrayana largely because of its teachers—because of their charisma, and their palpable compassion. The sparkling presentations of the great teachers are like beacons drawing people to them. You want to just be with the teacher, to hang out with them and hear what they teach, and ultimately to practice what they advise once the honeymoon has passed. There’s a process, which is not always so easy, of actually understanding and appreciating and benefiting from the practices.

One of the first obstacles is that ritual is not prevalent in many parts of the modern West. So a core challenge for many people is to be able to work with ritual—to be able to experience it as way to hold realization that one can gradually enter into and allow to seep into oneself, rather than experiencing it as a superficial traditional requirement.

Often people see ritual as a whole bunch of rules and forms. The obsessive mind kicks in and it becomes a pursuit: How do you do this? How do you do that? Certainly one tries to do things correctly, but when that dominates, the quality of the ritual as a means of teaching can fade away.

Larry Mermelstein: Yes, this has been a difficulty for many people. I’d say we’re doing the best we can, and one of the things we can benefit from is how many translator–practitioners we have to support that process. In time, many if not most people find a good relationship with ritual, but we should always be attuned to helping them along.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Another challenge in the West is that steps have to be taken to really include the body in practice. It’s possible to be reciting a mantra and imagining you are a deity but your body is completely checked out and not resonating with what’s going on. It’s all in the head. A certain amount of training is necessary just to help people be in their body.

Larry Mermelstein: I agree. I now appreciate how little awareness I generally have about my body. How grounded am I really? Many practitioners are becoming more appreciative of that as we age. The body starts not working so well, and that’s been a wonderful teaching for me. I was about fifty before I actually began to do anything about it, because the body was really falling apart.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Also, what we usually translate as “visualization” is something that is much broader than that word implies. It does a great disservice to what one is actually doing.

Buddhadharma: The word “visualization” is very eye-sense oriented.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Yes. It’s also very subject–object oriented. Our Western notion of visualization conjures up something like watching a movie, or watching TV. In the traditional cultures in which tantra arose, you never saw anything that wasn’t alive in front of you. Seeing has a certain richness and aliveness and freshness in that kind of culture. So, embodying a deity is not just done with the eyes, it’s done with the whole organism. Often people say, “I can’t visualize,” or “I can’t see it clearly.” We can also forget the power of the mantra itself to evoke the deity and her world, and the extent to which one needs to get out of the way and allow it to do that. Too often we stand in the way, and worry and obsess. It becomes a real interference with practice.

Larry Mermelstein: Making the ritual practice relevant and workable requires training, and probably a little more for Westerners, which is one of the jobs that our translation group takes on, in addition to simply translating. We try to help people engage with the texts and the methods in a way that allows it to become a natural extension of their prior Buddhist practice, rather than a bunch of new bells and whistles.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Yes. That’s good. I also think it’s very important to bring dharma understanding to the practice you know, so that one really understands absolute and relative truth and how the practice of tantra is showing you their union. That does not come automatically, so at the very least some basic Madhyamaka helps a lot.

Buddhadharma: As Rinpoche was pointing out earlier, the philosophical tradition provides the underpinning for the ritual.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Exactly.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: I work with a lot of students in America and I agree with Anne and Larry that there need to be progressive stages of training in the view of meditation, bringing it to one’s experience, and then manifesting that in one’s action. I would say, though, that the students generally are doing pretty well. Of course, the path is a path. There is a quotation from Maitreya’s teaching that the path at the beginning is mostly impure with lots of mistakes; in the middle, the path is half and half; toward the end, it is more pure and perfect. That’s what everybody goes through. Even in one sitting session. We start out very challenged, in the middle we calm down a little bit, and toward the end when we have to leave for work, we actually start to enjoy it. [Laughter]

Buddhadharma: Why can’t we just reverse the order, Rinpoche?

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: I was actually hoping we could create a machine to do that [laughter]. But it seems that progressive training in the three yanas is how it has always been done. And I think in all of our sanghas we have been trying to do that.

Larry Mermelstein: We are part of a very big, grand experiment of bringing an enormous cultural infusion of incredible wisdom that has come to the West from Tibet. We have rapid communications and the internet connects us across the globe, but the rate of transmission of the dharma has a kind of natural rate. We are very busy taking advantage of how much has been provided by teachers coming to the West, and we’re proceeding slowly from some aerial perspective. Or perhaps we’re moving quite quickly. Only future generations will be able to judge how we’ve done. It’s hard for us to see that since we are in the middle of the experiment. Overall, though, the students seem to be finding the teachings very useful and relevant and are connecting with them slowly but surely. Also, gradually, we’re beginning to understand the view better and getting a better feel for the practice, and we’re finding a way to mix them.

Buddhadharma: I have at times suffered from the syndrome of trying to be a cognitive superstar in working with these practices, rather than having a relationship with them that engaged my whole body and mind, a more intuitive kind of knowing.

Anne Carolyn Klein: Rinpoche said it all when he said a path is a path. And part of the path for many of us may be transcending the cognitive superstar syndrome. Because we’re so used to cognitive learning; we feel that if we can just get it intellectually, we’ll have it. On one of the very first visits that His Holiness the Dalai Lama made, he came to the University of Virginia and was sitting in Jeffrey Hopkins’ basement, which had been made into a temple. He sat on the floor. There were only about fifty people there, and he said that if you’ve been practicing for about five years and instead of getting angry ten times a day you only get angry seven or eight times a day, you should really understand that you’ve made progress.

I often recall that. It’s a very compassionate teaching. It helps people to understand the extent of the path—what a big job it is even to reduce your anger by 20 percent. Too often we idealize things. We suddenly feel we’ve changed radically and then are devastated when we see the old habits creep in again, as of course they will. The path is a path. It unfolds and it’s important to savor and appreciate that what may seem like a small thing is actually quite an important achievement.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: Patience is very important, especially in this time when instant gratification is expected. People think they must achieve something right away, and that becomes an obstacle.

Buddhadharma: Since realization is self-existing, it is available on the spot. Yet the path is so very long. How do you reconcile that?

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: By not trying to reconcile that. [Laughter]

Buddhadharma: That’s a profound answer. Thank you.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche:You posed a good question, and I should have a good answer, but I don’t. I’m sorry. [Laughter]

Buddhadharma:I thought not reconciling the instantaneous path and the long, gradual path was the answer.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: No. I retract that answer.

Buddhadharma: Shall we try again?

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: It is true that the Vajrayana teaches about sudden awakening, but all of those teachings are based on the idea that our mind is primordially awake, already awake. So, we discover that. That’s very different from instant gratification.

Anne Carolyn Klein:As I contemplate the dichotomy of all the challenges we have that can obstruct us, and the fact that in terms of treading the path we’re probably doing pretty well and are very well served, I am reminded of something I just read from Longchenpa: the fact of primordial buddhanature does not contradict the fact that there’s much to purify.

Larry Mermelstein: Trungpa Rinpoche said, “I have achieved the bhumi of patience due to the kindness of my students.”

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: Wonderful!

Anne Carolyn Klein:Another of the challenges is that we’re householders, by and large. There are constraints on the amount of time we have to practice. How much time is needed? Will a few short, intense retreats ever add up to what people were able to do in Tibet? That’s a huge question.

Larry Mermelstein: Indeed, the cultural context is quite different. And sometimes people have expectations about what kind of context is needed. For example, because of the importance of the guru–student relationship in Vajrayana, some students think they should be hanging out with their gurus. Yet we have something that is in a way parallel to that. We have so many books now that have been translated and commented on. These translations are careful and well researched. And the teachings, including video, audio, and written transcriptions of thousands of talks by various teachers—many have been compiled into books and manuals of instruction. Students in America today have an incredible wealth of ways of contemplating and revisiting the instructions they received orally. Add to that the great support of the many sanghas in the West who feel they are treading the path together. While there are challenges, there are many riches that generations of students to come can be thankful for.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: I would like to add that being in the room with my teacher, Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche, and receiving teachings, or even just sitting there with him, is very powerful. Feeling connected with him in that way is vital, and an experience that goes beyond reading his books. Both are very important.

Buddhadharma: The transmission quality is essential to Vajrayana.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: It certainly is for me.

Anne Carolyn Klein:>I don’t think I would have read any Buddhist books if not for the presence of my teachers, and the ability or the opportunity to discuss that with them. The books can be kind of tough, even in English. There’s something about the luminous presence of the teacher. Even just basking in the inspiration that they’ve left me with as I encounter the words I’m reading is crucial.

Buddhadharma: Anne mentioned the problem of finding enough time and the challenges of being householder yogis. How can tantra be made to work in this world today?

Larry Mermelstein: I firmly believe that tantric practice is workable in the world we live in. If the Vajrayana actually began with King Indrabuti supplicating the Buddha for teachings that would work for him as a king, who was not willing or able to give up his worldliness and responsibilities, by definition that means the Vajrayana teachings ultimately are meant for householders.

Our world is moving a lot faster than it probably was back in those days and so, yes, the stresses and complexities seem to be much greater than centuries ago. But so what? The very choicelessness of it is good for us. We have to do everything we can to incorporate the teachings on a continual basis in our lives, knowing full well that many of us may not have a lot of time for intense long retreat—though at times we might have some semblance of that. The teachings are geared to being applicable in our lives, as they are. It’s extremely workable. We have thousands of people currently engaged in that experiment in the West. Many of us, as Rinpoche was saying earlier, do experience the frustration of wanting it to be better, but that is the essence of path.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche: The Buddha’s response to King Indrabuti’s request clearly indicates that the tantric path is meant primarily for lay practitioners. In many of the mahasiddha stories, their families also begin to thoroughly engage in a Vajrayana practice. They manifest in many walks of life: as a carpenter, bartender, or farmer like Marpa. Khenpo Rinpoche has taught that it is primarily a yogi tradition. Of course we can be monastic yogis, but in many ways these methods are more suitable for lay practitioners, lay yogis and yoginis.

Anne Carolyn Klein:>Even if we feel that tantra is a workable path for householder yogis and yoginis, we still need to work with time management. It helps if we can constantly reflect on what is meaningful in life, and how precious time is. That is an extremely significant ongoing support for practice. It refreshes us. In the end almost any amount of practice is going to be beneficial. It’s not all or nothing. There’s a black-and-white thinking that can intrude. If I can’t be the next Milarepa, why bother? It’s always worthwhile to do what is possible and we need to get over the superstar, overachiever syndrome.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche is a meditation master and scholar in the Nyingma and Kagyu schools of Tibetan Buddhism. He is the founder of Nalandabodhi and the author of Mind Beyond Death and Wild Awakening: The Heart of Mahamudra and Dzogchen.

Anne Klein is a founding director and resident teacher at Dawn Mountain Tibetan Temple, Community Center, and Research Institute in Houston, Texas. She is also professor of religious studies at Houston’s Rice University and the author of Heart Essence of the Great Expanse: A Story of Transmission.

Larry Mermelstein is the executive director of the Nalanda Translation Committee, and an acharya, or senior teacher, in Shambhala International.

Reggie Ray is the spiritual director of Dharma Ocean Foundation, based in Crestone, Colorado. He was a senior student of the late Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and teaches within that lineage. He is the author of Touching Enlightenment and Secret of the Vajra World.