The Center for Humane Technology is featured in the Emmy award-winning Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma and co-founded by Randima Fernando. He talks about the promises and pitfalls of artificial intelligence, the existential questions it inspires, how Buddhism is uniquely suited to answering them, and how you can approach this new technology that has the power to change what it means to be human.

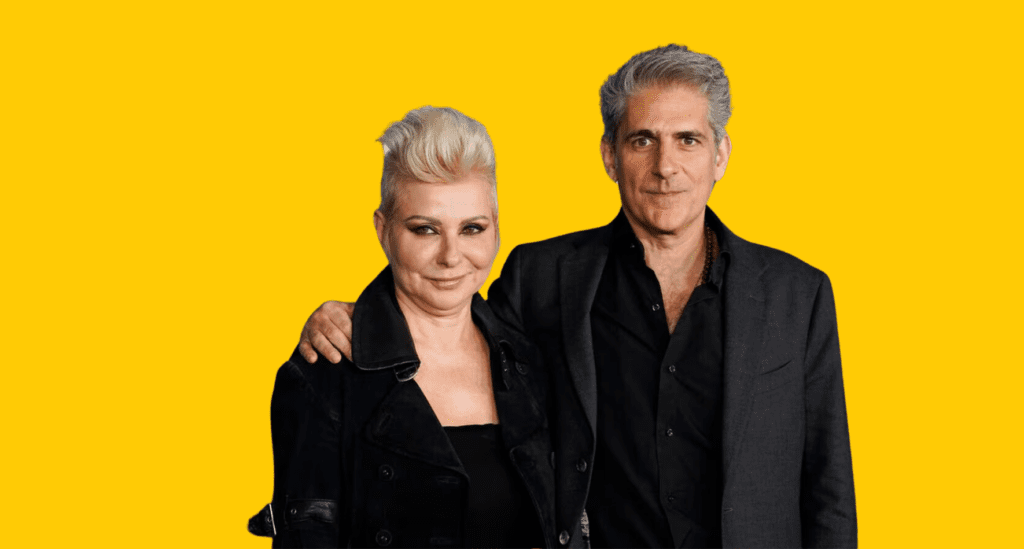

Sandra Hannebohm: Welcome to the Lion’s Roar podcast from the publishers of Lion’s Roar Magazine and Buddha Dharma, The Practitioner’s Guide. I’m Sandra Hannebohm AI can articulate the sum total of human knowledge, but can it help us cultivate wisdom and compassion? Today Ross Nervig talks to Randhima Fernando, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, a non-profit that helps realign technology with humanity about the promises and pitfalls of AI, a plethora of existential questions made even more pressing by the advent of this new technology, and how Buddhism is uniquely suited to answering them.

Plus, how you can approach this strange technology that will certainly have an impact on what it means to be human.

Ross Nervig: I’m here with Randima Fernando. Randy is a co-founder at the Center for Humane Technology, The center was featured in The Social Dilemma, an Emmy-winning Netflix film watched by over 100 million people globally. he’s also a board member of the Spirit Rock Meditation Center. Randy took time out of his schedule with us to talk today about how to navigate this world of swiftly changing technologies. Welcome, Randy.

Randy Fernando: Thanks for having me.

Ross Nervig: Yeah. So tell me about yourself.

Randy Fernando: So, my background is a mix of Buddhism, non-profit work, and technology. It’s kind of an interesting combo. I was born in Sri Lanka, and I was born into a very, I would say, very Buddhist family. I feel very lucky to have learned about Buddhism and computer programming both at a young age. And it’s been interesting to see how those paths combined in my life. My mother taught me Buddhism. and taught my sister as well, and my father actually introduced me to programming. My granddad was a dharma teacher, so we got a lot of books and instruction every summer when we were in Sri Lanka. So, it’s not surprising that Buddhism has always resonated so much with me. But I also loved programming. I loved lighting up pixels on the screen especially. And so, I came to the US to study computer science and computer graphics and ended up at NVIDIA in Silicon Valley, which is where the coolest computer graphics work was happening at the time. So I got to work on some really interesting software products and to author some books on advanced 3D graphics there.

But after seven years there, I got really interested in the non-profit sector and so I made a jump there. I had been volunteering for two years at a small organization that was teaching mindfulness to kids and educators. And as you might guess, I thought that was a great idea. So, I eventually left Silicon Valley after juggling both of those.

I was like, okay, let’s make a shift. And I served as the executive director of that organization, which became Mindful Schools. I did that for seven years. We were one of the early, one of the pioneers in high-quality online mindfulness training at scale, and we thought very carefully about what we quality, and representation, an honest representation of secular mindfulness and its benefits.

And over the years, Mindful Schools has now reached, I think, more than 50, 000 educators and millions of kids globally. And for the last six years, I’ve been a co-founder and formerly the executive director at the Center for Humane Technology.

Ross Nervig: So could you tell our listeners a little bit more about the Center for Humane Technology?

Randy Fernando: Sure. As you said, our mission is to realign technology with humanity’s best interests, because I think, as we all know and can feel viscerally, that certainly isn’t the case right now. As a simple example, think about how much time people typically spend meditating or wisdom building. And you know, we’re thrilled if kids can meditate for five minutes or ten minutes.

And now think about how much time we spend on our devices or with technology with forms of training that are not wise. So, as you said, many folks know the Center for Humane Technology from the Social Dilemma. These days, we are focused, fully focused on using our platform and network, and partnerships to help address the AI situation wherever we can.

Center for Humane Technology has a lot of helpful resources. Just want to mention that there’s an excellent presentation from my fellow co-founders Tristan Harris and Issa Raskin.

Called The AI Dilemma. Check it out on YouTube. It’s very informative. And a thought-provoking podcast we have called Your Undivided Attention. And we have a course called Foundations of Humane Technology. There’s a lot more stuff, but at all at Humantech.com.

Ross Nervig: That’s great. I watched the AI Dilemma, and my jaw was on the floor. It was just, it’s, in some ways it was kind of hard to watch just the truths being told. I don’t know. I really appreciated it. So in a previous conversation, you mentioned how grateful you were for the Buddhist operating system that your parents imparted to you.

Can you tell me more about this operating system?

Randy Fernando: Sure. Yeah, I use those words in the context of we were talking about technology, and I think… Everybody has some kind of, we could call, operating system, right? Some kind of principles and sense of, like, what is a good life, right? That, they use to guide their behavior. For me, Buddhism has been a very explicit definition there and a definite a clear resource.

And what I like is that it’s a principles-based approach. Meaning, these are ideas that, that work. They help you understand the world, even when the world is changing all the time. It’s not a fixed set of things for any set of circumstances. It’s a general set that adapts to basically every circumstance.

At least in my life, it has worked well. And I could say there are very few things that are actually true like that. And certainly not things that have been true for 2,000 plus years. Very rare. So all these ideas like the Four Noble Truths, or the Noble Eightfold Path, all these things… The precepts, being introduced to those early, I think, has been very helpful.

And they help you be clear about meaning and purpose. Some of these really big questions. It’s good to know where you’re trying to walk toward. What path are you on? Even if you’re sort of very early in that pathway and you don’t fully understand it, I think it’s still very helpful. And it answers these deep questions like, what is thriving, right?

Like, what is the wisdom that guides your value system and guides your thoughts and actions, and speech? So it’s been a really helpful framework for decision making, and then also it’s something you can discuss with your friends or your loved ones and try to make improvements when you do something that you don’t think was wise.

And the other thing I’d say is it narrows the menu of options really well, which is helpful because sometimes there’s so many options in life, but if you have a framework that’s helpful and sort of an ethical framework that you’re trying to follow not perfectly, but trying to follow it narrows the options and helps you focus on maybe the better ones, the better options, and keeps you from having big regrets.

So those are the kinds of things and the very last thing I’ll say is There’s one concept that’s been, I think, particularly helpful with respect to technology. And that’s this idea of dependent co-arising, right? The idea that everything aside from nirvana right, in our Buddhist framework is shaped by conditions.

So, lighting a candle requires several conditions, right? Like some kind of fire or spark and the fuel in the candle and oxygen in the air. Those come together. When one of them depletes… The candle is no longer lit. And so, this thinking of everything in this conditioned way, uh, I think is very helpful. And Thich Nhat Hanh gave this great example right, that’s more complex. He held up a sheet of paper and he said, Look, I see the cloud floating in the paper, and the rain, and the trees, and the sunshine, and the logger’s food, and the logger’s parents, it’s really beautiful, it’s worth looking up.

But this is, this understanding leads to the idea of interdependence, and I think this conditions-based view of ourselves, of our technology, of our society, is really helpful, as we take a, we look at the products, we look at the systems, we look at the people involved in building them, and we can see how the prevailing economic systems like capitalism, don’t account for this well, and then you run into various problems.

So we’ll talk more about that, I’m sure, but just wanted to introduce this concept because it’s, you can derive a lot from one, this one concept.

Ross Nervig: So with AI, I feel like humanity has passed through this monumental threshold. In some ways, without really realizing it do you feel the same? How should we be thinking about AI and its impact?

Randy Fernando: I would say yes. I think it’s a big moment. Many people in the artificial intelligence and social science worlds are tracking this very closely, and they’re keenly aware of… There’s different thresholds, and so it’s worth talking about that a little bit.

So, so first, I think we should talk a little bit about what is a neural network and what is all this AI stuff. So, basically, the generation of AI that we are talking about is built on neural networks. So neural networks mimic the brain, and each of the neurons has different strength. Of connection between them, different weights, and this is kind of how our brain works as well.

So when we train, when we do something repeatedly, the connections between neurons get stronger. And so there’s more preference towards those pathways. And so we’ve now had, we have these models of billions of connections. And they’re trained on massive data sets and a lot of computation that goes in.

And the training process assigns weights to the, between the neurons. That’s kind of the simplest way to understand it. And so they really are mimicking our brains in some way. And so now these algorithms train on images, audio, videos, not just text. And then they’re tuned with what’s called reinforcement learning with human feedback.

And so humans… They sort of, they’re asked different questions about the answers that the algorithm, that the AI gives and it’s able to change the weights and make it more and more usable, basically. Uh, Just trying to keep it very high-level here. But and so these simple neural networks have been around for a while.

And we’ve actually met them before in social media. So often, we call that first contact. Engagement-based algorithms, right? Artificial intelligence were sorting for posts or texts or media for billions of eyeballs. And even that caused a lot of trouble, as we saw, right? There were all of these problems and the social dilemma talks about it.

Part of the challenge with neural networks is that… They’re not the typical kind of algorithm that people think of, like these kinds of step-by-step, if this, then this, then, you know, there are these branches, and it’s all very procedural like you can follow the steps and understand how it works. These neural networks have all of these neurons, with all of these weights, and different parts light up based on the inputs, and it’s very, very hard to understand what is going on.

And in fact, nobody really understands them yet. We just know they produce quite good results. And so there’s definitely a lack of transparency that causes problems. But so, you know, speaking of thresholds, right? So there are these simple neural networks that we encountered in social media. Then there’s generative AI, which has been all the hype in the last few years.

So text, images, audio, video. Each one of these is sort of… ranging in difficulty. Video is the hardest, right? Generating video is very difficult, but each of them we’ve become very good at now. Video is the one that still has some work to get done, but images, audio, and text are very high quality already.

Then there’s general purpose AI, which is able to add reasoning, sort of cognitive capabilities, reasoning capabilities. So then the next thing after that is this kind of… artificial general intelligence, AGI. People have different definitions of it, but basically, I think one helpful definition is when an AI can match human performance on intellectual cognitive type tasks. There’s superintelligence, which is intelligence far beyond what humans are capable of. And the other thing I want to remember here is robots. They are being trained very quickly as well. So there’s this tendency to think, Oh, this is just the intellectual realm.

But actually a lot of these same techniques are being applied in robotics. And they are able to train in simulation and then download the learning to physical robots.

So these are kind of key junctures. And where are we right now? We’re sort of at this general purpose AI step. We’re not at artificial general intelligence, but I wouldn’t say we are very far away.

So I think it’s important not to get stuck in a naming debate and think much more about, okay, what are the real things, the real consequences that are unfolding, and what do we need to deal with?

Ross Nervig: So, I feel like that begs the question, why do we need humane technology?

Randy Fernando: It’s a great question. Without a doubt, we need technology that’s aligned with humanity’s best interests. And I think part of the problem here is that the systems that the technology lives in tend to cause it to get misaligned. And over time, the level of misalignment has grown tremendously. as a result. So, let’s talk a little bit about how that happens, right? Let’s take a systemic analysis of the situation. If we have systems that are misaligned, the conversation is much more about misaligned systems and misaligned incentives more than bad people.

It’s just we kind of rotate the people in the system as placeholders, but whoever is in there is responsible in certain ways, right? There’s certain incentives. There’s the system, there’s power, there’s wealth, there’s status, recognition, cultural conditioning, competition, the thrill of discovery. I think people forget that one a lot.

These are what drive these kinds of technological innovations and lead them to get misaligned.

So there is a great systems thinker named Donella Meadows, and she wrote an essay called Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. And so we use that analysis when we look at systems. And basically what she was identifying is there are different factors that affect behavior inside the system, but at the top is the paradigm or the mindset that the system operates from. And so, the system that we have our sort of capitalist… the system that dominates most of the world is built on assumptions like growth is good, resources are here to be extracted, to serve human purposes, um, people are rational actors. There are all these assumptions that are baked in.

And that has significant consequences. So, the other thing about the capitalist system is that it’s brought us a lot of advantages. Advantages in food, clothing, shelter, medicine, communication, information, technology, convenience, all of these things. But a big part of what’s changed is that we have now reached environmental and human societal limits.

And so when we run that same algorithm which is really based on competition and extraction, and when you multiply those together and you exponentiate that with technology, now you start to have some real problems. So we’re seeing exceeding ecological limits. We are seeing exceeding the limits of our own minds, our attention, our mental health, these kinds of things. We are exceeding the limits of democracy, where we are breaking down sense-making, our ability to make sense of the world, to know what’s true or false. And so when we just continue to run and run and innovate and do these as quickly as possible, then we run into big problems.

So this is what I want to ground that the idea of humane technology can’t exist in isolation. It has to exist inside of these systems that are actually governing the technology. And so we use this term called the multipolar trap. Kind of this race to the bottom that happens where the only way to operate is to compete with everyone else.

And to keep exceeding these boundaries, because if you don’t compete, you lose. And so if you want to stay in the game, you have to keep doing this. And so you end up with AI companies rushing to roll out image generation, audio generation, video generation, all of these things. And then you end up in a world where they’re all competing to capture market share without considering the impact on sense-making. And so now we don’t know what’s true, right? It’s already happening, and it’s only going to get worse, where we look at images, audio, and video, and we have a really hard time proving a point saying, hey, I wasn’t there, I have video evidence, or, look, here’s a photo.

And these things will no longer be good forms of evidence, or and, even if you can prove it in one form or another, the doubt that gets permeated throughout society causes all sorts of problems. And you can see how every company is running ahead to integrate AI as quickly as possible. You see it in a lot of advertisements, companies proudly talking about that.

But what we’re also doing in that process is reducing consumptive friction. We’re starting to consume things with less and less thought about it, less and less kind of wisdom, and just running ahead. So all of this, I think, goes against the Buddhist principles. Another good example is where TikTok came along, right?

And they had these super short videos, and they caused everyone else to release versions of super short videos. And YouTube shorts, Instagram reels, and you get this competition. But what does that do to our minds? Now our attention gets sliced shorter and shorter. So these are all examples of how the governing system can take technology and turn it bad. And so when we get to this topic of humane technology, so say we were able to design the systems better, there are still some aspects that we need to consider when we’re building technology. So for example, it needs to start with a good definition of what is thriving. And again, I think Buddhism offers some very good answers there, right?

The first noble truth about dissatisfaction, like what is it that causes causes this kind of discomfort that just permeates through life, or like, what, how do we, what causes that, and how do we address that? We have to have some answers there. So starting with the clear definition of thriving, and how can we help people act in alignment with their deeper intentions?

Rather than optimizing for engagement, for example, we have to center values. We have to say, okay, How do we make sure that the metrics of the data-driven product development cycle don’t hijack the values that we intended? What are our values? Are we clear on those? Do we understand that technology isn’t neutral? It’s shaped just like everything else by conditions. How do we make sure that harmful consequences are minimized and we’re not causing undue harm somewhere to people, to the environment?

And how do we bring those costs back on the balance sheet so we’re behaving fairly? How do we respect human limits? How do we work with innate human nature, and cognitive biases instead of hijacking them for financial gain? How do we make sure the world is more fair and just? And how do we integrate the voices of people who experience harm? How do we create shared understanding instead of fragmenting it into all sorts of different pieces and different realities? We are going to be seeing, I think, more of this, because we already had this problem with social media, where people were getting different customized feeds. But now, with AI, it’s not like there’s one chatbot that has the golden answers.

It’s very easy to tune different chatbots for different audiences. So each one will be going to their sort of, their oracle and getting different answers that might conflict completely. Some might be, like, provably false. And so, this is kind of, you can see a big mess coming in that realm. And we, ultimately, when you try and get the systems aligned and get the tech aligned, you have to match power with responsibility. And so, how do you do that? I mean, these are some of the big questions.

Ross Nervig: So that leads me to think about mindfulness. Can you tell me about your thoughts about the relationship between mindfulness and technology?

Randy Fernando: Unfortunately, more often than not, they are at odds. Attention is the most valuable currency we have, and it’s what we need to guide our intentions, and our behavior, and everything. So, the fact that they’re at odds is a big problem. Because technology is driven by an economic system that financially rewards hijacking attention and breaking down mindfulness there’s this tension keeps coming up.

So, for example, in social media feeds or advertising business models that actually try to take your attention and sell it to a third party. This is also something to keep in mind with new technologies, like virtual reality augmented reality, or wearable tech. See if you can identify what the incentives are for the company that’s offering the product.

This isn’t to say that these products Can’t be helpful but they’re at their best when they help to set up a space for cultivating mindfulness or, let’s say, providing feedback that helps you refine your technique. The best technology helps to set those conditions for mindfulness or authentic interaction, let’s say, like a video chat.

And then the tech steps away instead of trying to hook itself to you more deeply. It’s also helpful to consider how technology conditions us. How is it conditioning, how is it training you during the experience of using it, but also afterward? Do we become dependent on the technology? Are we unable to meditate or be our best selves without it?

And this is interesting. It’s true even of guided meditations, for example. If we’re only doing guided meditations, we are probably missing out. Pure stillness is an important experience and training also. And then there’s the question of how well we can carry the meditation training we do on a cushion or in a chair into real life. So, what about chatbots? I imagine this is a question on many people’s minds right now. If you look at the best one that’s available, which is a GPT 4 via ChatGPT’s paid plan, that can be quite helpful for questions we might have, especially if we don’t have access to a teacher. Now, I want to say this is a tricky area for many reasons, but because even the best chatbots can give quite erroneous answers sometimes.

These are hallucinations, as we call them technically, but the problem is they always do it confidently, and in areas where you might not know as much, we might not be able to tell. I’ve done testing with friends who are also experienced mindfulness teachers, and I can say that GPT 4-level chatbots at least do a pretty good job.

And that’s because there is a huge volume of wise people’s writing that the chatbots have been trained on. So, you go, and you tell it to be a wise Buddhist teacher, or a Theravada, or Zen tradition, you can specify. And then you can ask some questions. The challenge is its responses get much better the more context it has about you, and that’s one of the tricky points with respect to privacy, use of your data for AI training, or even potential hacks of data that you’ve sent.

If you kind of get past that, you can sort of anonymize your information to some extent, so that It feels safer, um, but I want to name that there’s a real trade-off here. Ideally, everyone would have frequent access to a very wise human teacher, but for most people, that isn’t the case. So, as chatbots improve, there may be ones that wise human teachers test and approve for simpler or medium-level questions, and then there can be an escalation path for more complex questions involving psychology, or just kind of deeper knowledge, or more complex practice questions. As a community, I think this whole discussion is a very important one to have. And I also think that the views of both teachers and yogis will vary widely. The one thing I would say is that those who are discussing this topic should definitely check out the technology first so they’re well-informed when we actually have those discussions.

One other note I would say between mindfulness and technology is it’s very hard to beat tech that’s trying to hijack your mind, no matter how much you’ve trained. Even very experienced meditators struggle with this. And so the answer here is actually forms of renunciation. Renunciation is just, we don’t talk about it that much because we want, it’s again coming back to this underlying mindset of growth and more.

And renunciation is not talked about enough as a consequence of that, changing the environment, changing our proximity to the devices, changing the dosage of the technology um, reducing notifications everywhere, using tools that will help us to monitor usage and limit usage, put boundaries, same things you would do with a child, you know, we should do them as adults as well. It’s also interesting to watch our mind and body, breathing, and vedana, this sense of pleasant, unpleasant, is very palpable as you use different products.

And if you can catch those moments better, you can; those are points of intervention, and that’s helpful.

One other aspect of all this is this idea of sense-making, how we make sense of the world. And even if you’ve cultivated a very high degree of mindfulness, you still won’t be able to tell if a realistic fake image or video or audio is real. But what mindfulness can help us do is to pause and take a good look at it before trusting blindly or forwarding instinctively.

And that in itself is quite helpful.

Ross Nervig: So on a technological level, where’s the world headed? What does the future hold? Where would you like to see the technological world go?

Randy Fernando: This is an important question, and a lot of times we use this quote from the renowned sociobiologist, Dr. E. O. Wilson. He said, The real problem of humanity is the following. We have Paleolithic emotions, Medieval institutions, and god-like technology.

So the problem is that our physiology and laws can’t keep up with the exponential pace of technological advancement. And so what happens is the technology systems, and the companies end up finding new ways to hijack or circumvent the rules that exist. So, you know, in, in a dream world, I would love to get out of this sort of competitive extractive mindset. but that’s a lot to ask for, and so there’s sort of two worlds, right? There’s one world inside of the current systems we can talk about, and then there’s a different world that we could talk about that’s kind of more dreamy, but it’s, I think it’s important to, to have these aspirations. So, in the current world, the main thing is we have to have the rules of the game have to be updated to match our technology, to keep up. And this is very hard because the technology is changing, especially with AI. It’s changing every few days sometimes, definitely weeks, months. The frequency is so high. And in a world of broken sense-making, attention hijacking, cultural shifts away from interdependence, democracy that isn’t functioning well, where people are caring more about influencer culture and less about each other, these are all conditions that make it harder and harder to collaborate and change these rules, fix the problems. And this is why this kind of the sense-making problem and these others become primary. Because you just can’t fix anything else if you get this wrong. But inside of this world, once in a while, we do get a chance to pass laws or create a movement, and the key principle there is that whatever move we make has to connect back to price. It has to come back, the cost of doing the wrong thing has to come back on the balance sheets of companies. There has to be real liability for doing the wrong thing. And in cases where there are future unknown harms, we need to have mechanisms where if a prudent path isn’t taken, there is some way of saying you ran ahead irresponsibly. And now there are consequences for doing that. So these are some examples of what we can do. And then thinking about this other world, right? Like how can we really do better? We should take this AI dilemma moment as a moment of reckoning; it’s similar to moments we’ve had around climate, around inequity. This time, even more people across all lines of citizenship, global citizenship, gender, race, and socio-economic class, are all going to be affected. In a big way, I mean, all of these aspects, right, so sense-making, being able to make healthy choices, mental health, forms of discrimination, all of these are going to happen, um, and these cultural shifts, where we just end up in a culture that’s not healthy, but also jobs.

Jobs is a huge aspect because now, these technologies are very cognitively strong, which means there’s much more exposure for bachelor’s, masters, and sometimes even Ph.D. level folks. And many of those people have more leverage in the system to make changes. I think the impact on jobs will be huge, with hundreds of millions of people displaced over the next few years.

No one has explained… Why that won’t be the case. I’m waiting to hear that. You will sometimes hear CEOs say things like AI will create jobs. Of course, it will! Like, that’s different. They don’t talk about the net. So I think when we get a chance to ask questions, we should probe into this and say, okay, in net, what do you think is going to happen?

There’ll be benefits, and there’ll be harms, but the ordering matters, so like, ask about that. These are ways we can be helpful. Based on what AI models already offer based on the capabilities that AI models already offer, And real examples of what they’re already being used for. I think it’s so clear that many jobs are going to be at risk. So some examples are customer service jobs, right? Accounting, financial analysis, artists, photographers, musicians, and automated driving is coming quickly, right? So many people rely on Lyft or different forms of delivery as their job. Robots are coming in fast food, right?

But even things like programming, that people often think of as well-protected, it turns out programming is a form of language, and so generative AI does programming fairly well and again, is improving very quickly. So, there’s going to be a lot of exposure here, and I want to bring attention to that because, again, this is a moment of reckoning, and because so many people are going to be affected, It’s a chance to ask for a different system, to make changes that people across the political spectrum will want made because they’re all going to be affected.

So I see that that is the most positive way to see what could be like a brutal situation. Because we actually will have the ability to have better lives for many people. We just need to have a better way of using our technology to address food, clothing, shelter, medicine, the basics, making sure people have those, while also incentivizing hard work and innovation that is wise.

Ross Nervig: So, you know, taking all these issues and problems that technology might create in our future or in our presence what solutions can you name?

Randy Fernando: So, we talked about some of the solutions in the system. So, I want to speak a little bit about what people can do listeners. So, one is get educated about these issues. I think it doesn’t really help when there’s a lot of inaccuracy floating around. And in the Buddhist community, there are steps we can take to be more informed. I would highly recommend that these kinds of podcasts. There’s a lot of resources that we produce at the Center for Humane Technology that can help with that. And then share them with other people. Help to educate others. And then, I actually think Buddhism can play an enormous role in the future that we have coming, right?

There’s this moment of reckoning that’s coming. And in that moment, clarity on thriving, on mental training, On kindness, on equanimity, these are topics that become extremely important because… When you want to design a kind of system that’s going to serve people well, you have to start with the core principles of, like, where does unhappiness, you know, dukkha? I prefer the Pali word because it captures so much more nuance.

But if you want to say forms of dissatisfaction, where is that coming from? And where do forms of more stable happiness come from? There are different forms of happiness. Some are very unstable. They’re based on conditions that change quickly, and then there are other forms of happiness that tend to be more stable and fulfilling, even if they’re not perfect. This is our realm. This is the realm of Buddhism and simplicity, and how simplicity can be helpful so that we focus on the right things in those conversations in this huge moment. So that’s what I would ask, is whatever your role is across society, think about where we can apply these teachings and this wisdom because there are a lot of ways we can be of service as a Buddhist community

Ross Nervig: This all makes me think of the scope and power of AI. It seems almost god-like. How will AI help spirituality? How will it hurt spirituality?

Randy Fernando: This is a tricky one. I had to kind of lookup. I was like, okay, how do we define spirituality? The dictionary says the quality of being concerned with the human spirit or soul, as opposed to material or physical things. This is kind of important because sometimes people use spirituality as a word to say faith in the unprovable, or like, you know, spending time on the unprovable.

And I’m certainly less interested in that realm, and I think one of the beautiful things about the Buddhist path is that it’s all explorable, and at least the core teachings are explorable. You can test them with your own experience, and you can learn. So I’m trying to answer with… With that lens um, I think one of the most profound things that will happen is that AI and other innovations could redefine what it means to be human, or how it means to exist, because there will be augmentations.

There will be, first of all, simple augmentations like augmented reality, so putting on a headset VR or AR kind of thing so virtual reality is fully synthetic. Environments that are transmitted to your eyeballs right, where it’s, you know, you look, it feels like you are in a 3D environment.

Augmented reality is where you see the world as it is, but it’s got these augmentations, so you might see additional information or new objects superimposed, kind of interacting with the rest of the environment. And these things are happening with headsets that are already commercialized. Wearables are getting closer to the brain.

Just even like the things you put in your ears, just the pods you put in your ears, are now, next generations are going to start monitoring brain activity in the ways that they can, right? There’s going to be headsets that start to try to do that. And then you have this idea of AI augmentation, where people might start to put chips in their brains right, so it starts to get quite dystopian. So we have to think a lot, again, back to first principles. This is where, again, the Four Noble Truths are so powerful in clarifying what is it that you are chasing and why. So, if you understand where that prevalent kind of, there’s the dissatisfaction comes from, and you look at it and say, well, it’s actually, there’s a deep misunderstanding of the impermanence of things, and why things change, and how complex the conditioning is behind them.

And it’s because we don’t understand that well, or accept it, that we run into all these problems. That’s a different conversation. And so then you say, well, there will be people who choose not to get augmented, and there will be people who are very excited about that. We’ll have other problems, like sentient artificial pets, sentient seeming artificial avatars or robots.

And one of the things that pains me, and I’d really like to avoid, is a world where we get really interested in those problems or those rights. And leave behind humans who, humans and real animals and real nature, um, that we should be talking about. Because again, it’s this, that comes back to the principle that capitalism is sensitive to capital.

So the new innovations… will bring a lot of attention, will bring a lot of resources, will bring a lot of interest in these questions around their sentience or their rights of these new virtual pets, these artificial, you know, pets or robots, and again, it always leaves behind people who don’t have capital.

And so you’ll get these, like, richer people interested in all these really interesting, you know, interesting conversations about their virtual pets and the rights and the well-being of their pet robot, or whatever. That’s where it always goes. And this is why we always follow this pattern.

So I just want to name these challenges. We actually did a podcast episode recently with Dr. Neeta Farhani about… cognitive liberty. This is a concept that she coined, but the need for protecting cognitive liberty in this new world where we can have we’re starting to see inside the brain, we can understand fMRIs and see what people are thinking, and yes, that is being used for interrogation in authoritarian governments, really scary stuff, and, and I think one of the challenges is, these technologies sneak in because there will be positive, useful things that they’ll be able to do, and maybe you’ll start buying it because it helps you with, maybe with your meditation or something like that, or it helps your parents, you know, monitor their health or something like that, but all these other side effects kind of sneak along in the process.

I think that’s part of the problem. And then, eventually there aren’t any other products on the market that don’t offer the new, more invasive… features. This is what tends to happen, and so we need laws and even rights-level protections that can protect us because it’s very hard to do, the market doesn’t tend to do that very well. So back to your question, you know, it’s sort of like, will it help or hurt wisdom? I think there are aspects that could, we could have very good spiritual teachers, therapists, this kind of thing, where people don’t have access, you know, there’s this reaction that comes immediately, saying, It’ll never be as good as a human.

Only humans should do those kinds of things. But a lot of people don’t have access. This is the problem. If they all had access to other humans, maybe that would be very good, but hundreds of millions of people globally have mental health issues, and they do not have access to therapists.

Not just the money, which is prohibitive for many people, but also the frequency that they need. To really make advances, you need to talk to people frequently. So how do we do that? And maybe there’s a way of having a tiered approach where some level of basic questions can be answered by these kinds of chatbots that are well-trained, right?

Cautiously trained with good protections and then there can be referrals to humans for the more difficult questions. This is all very, you know, fraught territory, but I’m just, you asked me the question of how will this advance, so these are some thoughts on what could happen. And again, chatbots can be trained, you know, politically, but also to represent many different religions and traditions, some of which could be extreme or harmful.

So, we need to keep that in mind as well, right? As these technologies become very democratized, all sorts of things can happen. And so, it’s hard to, it’s hard to make the predictions.

Ross Nervig: Yeah. So, my last question is how should somebody approach a strange new technology?

Randy Fernando: So this is similar, I think, to the previous discussion, and a lot of what I’ve said is I like to go back to first principles, which is again why it’s useful to be clear on what the principles are. I mentioned this kind of condition and training lens before. I think that’s really helpful. Using a training lens to think about technology helps us see the ways it shapes us individually and societally, right?

Like, it’s not just an individual thing. I think this is one of the traps that we fall into in the mindfulness Buddhist world is sometimes it can be two individuals, especially the Theravada world, which is what I’m most familiar with. The interconnections are very important, and the collective training process is very important.

So, how is it training you? That’s why I would ask that question. And it’s not just the experience of using the technology. It’s what stays with you afterward, right? The training, the wiring, especially when you use something a lot, stays with us, and it’s quite hard to rewire. The training required to rewire is, can be very high. What does your definition of thriving tell you about it? How is it contributing? So again, back to the Buddhist realm, it would be, you know, understanding these, kind of, the core concepts, dukkha, anicca, anatta, these kinds of things. But also, like, the Brahmaviharas are great, right? So it’s, how is it helping you with compassion, with loving-kindness, with sympathetic joy, right?

To understand. Join other people to understand their conditions. What is it that’s making life harder for them? What’s making life better for them? And balance, right? Equanimity. How can we be more balanced? Because ultimately, being more balanced is really helpful, right? How dependent are you on it? This is another thing. So, for example, a technology that you can’t meditate without or that you can’t be mindful without is probably harmful. So, things like that, like, if you’re only a, if you’re sort of a better person with the technology and you’re not great without it, that’s not good.

There are some real challenges, for example, with the chatbots, because they’re going to be very charismatic, friendly, and easy to talk to a chatbot, right? Therapist-type chatbots. But if that’s the thing that you interact with a lot, to say kids as they’re growing up, if they interact with that a lot, Now this can be very harmful because you don’t, you lose the ability to learn how to interact with other people.

Because in real life, it’s not always easy, right? Other people have tensions; they have conditions that shape their lives. and the way they show up when they talk to you. And if you’re not able to navigate those situations uh, you probably won’t do as well in your life. You’ll suffer a lot. So, that’s an example where something innocuous, like a friendly, well trained AI chatbot that sort of checks all of the boxes. It’s good on privacy, it’s good on language, it doesn’t use harmful stereotypes, right?

It’s sort of really well-trained and aware and thoughtful and compassionate, but still can lead you astray. Some friction is very important, I think, in our lives, and this is a challenge we have with modern technology. This is the instant gratification problem and the resilience problem, where our resilience gets weaker and weaker because the friction in our lives Gets less and less.

So this is happening all the time, and we have to be very aware of it. I think this shows up a lot when we go to retreat. There’s a problem of having preferences on retreat, which is really important to navigate, right? To learn how to navigate discomfort. And because we just get used to having things comfortable and easy and fast all the time.

Ross Nervig: Well, Randy, I love talking with you. Every conversation we have, I feel like my mind gets blown two or three times at least. Do you have anything before we go that you want to plug or talk about? Anything you want to share that’s upcoming for The Center or upcoming podcast episodes? Anything you want to share?

Randy Fernando: I’d recommend checking out our website, humanetech.Com, and our podcast, Your Undivided Attention. , which is at humanetech.com/podcast. it’s a very wide-ranging podcast. It covers psychology, the sciences, geopolitical dynamics, and all of these in the intersection with technology. And Tristan and Eiza do an amazing job on the podcast.

It’s very engaging, and we edit it very carefully to make sure that it’s a learning experience for listeners. So, please check it out.

Ross Nervig: Thank you, Randy.

Randy Fernando: You’re very welcome. Glad to be here. Thanks, Ross.

Sandra Hannebohm: Thanks for listening. For more on the future of technology and spirituality, find the article What AI Means for Buddhism at Lionsroar.com.

Mission-driven, non-profit, and community-supported, Lion’s Roar offers Buddhist teachings, news, and perspectives so that the understanding and practice of Buddhism flourish in today’s world and its timeless wisdom is accessible to all. We do this by providing as many entry points as possible through print and digital publications, our website, video, social media, online courses, practice retreats, and more. We try to bring dharma to people right where they are, knowing the difference it can make in their lives. You can help us spread the dharma by leaving ratings and reviews. Or go to Lionsroar.com to subscribe and get unlimited access to online articles, new magazine issues, and several collections, plus perks and exclusives from Lion’s Roar Magazine and Buddhadharma, The Practitioner’s Guide.