Realizing emptiness, shunyata, lies at the heart of the Mahayana journey to enlightenment, but how does that happen? What examples and instructions are there to follow that make the realization of emptiness authentic experience rather than an imagined state of blankness? We can begin with the “Perfection of Wisdom” scriptures—the Prajnaparamita sutras—which praise great bodhisattvas as brave beings fully dedicated to awakening for the benefit and well-being of all. They’re praiseworthy not simply because of the deeds they perform, but because they have looked into all the dark corners of their experience, to free themselves from delusion, and yet they willingly remain in samsara to liberate others. They embody the sublime union of vast, compassionate action with the profound wisdom of emptiness.

Such deep looking into the nature of experience is intimately linked with the great scholars of the Nalanda tradition—such as Chandrakirti, and the brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu, to name a few. Within this monastic university, they actively engaged in meditative and interactive inquiry into the nature of mind. They intensified the illumination of the Mahayana teachings. They did not, however, focus on intellectual mastery—the primary emphasis of contemporary scholarship. Instead, these practitioner–scholars used intellect to guide and sustain their contemplative practices, such as meditations on the selflessness of persons and the emptiness of phenomena. We follow in their footsteps to this day, and the spirit of Nalanda continues in practices that lead us to the wisdom of sunyata in ever-subtler ways until we fully embody it in the ways we act in the world.

First Steps

We might begin treading on the path of emptiness meditation with the Foundations of Mindfulness Sutra, in which the Buddha invites us to place our bare attention on the body, feelings, mind, and sense perceptions. We are encouraged to be mindful of the body while sitting, standing, walking, or lying down. In meditation, we bring mindfulness to feelings of attraction, repulsion, or indifference. We take note of sights, sounds, smells, and tastes, as well as our discursive thinking.

These four foundations of mindfulness are often taught as part of the practice of shamatha or “peaceful abiding” meditation, learning to stay with the body as body, feelings as feelings, and so on. These four objects of meditation provide a useful basis for cultivating stability, gradually developing the mind’s inherent strength. There are also hints here pointing to egolessness, the absence of a solid sense of self.

In this practice, the Buddha suggests placing attention on the physical form of the body breathing, while taking note of the various sensations and feeling tones (pleasant, unpleasant, neutral) that arise and dissolve. Reading this sutra, contemplating its meaning, and meditating are steps on a path of developing discernment, distinguishing somatic from emotional dimensions of experience, noticing differences between mental chatter and sense perception. These various aspects of experience are not one big solid block, a looming monolith. Practicing in this way, initial insight into the parts and particles of our experience is close at hand.

What we call me or I or myself has both physical and mental parts. As even a quick glance shows, the body is not a singularity but a diverse multiplicity of feet, legs, torso, arms, head, and shoulders. In turn, the foot has toes and a heel, legs have ankles and knees, hands have fingers and a thumb, heads have eyes and ears, a nose and mouth.

The psychological dimension of our being is similarly plural. In a single session of sitting meditation, we may experience likes and dislikes, fantasies and regrets, anxieties and hopes, memories and anticipations. We are offered a feast of conflicting emotions. The main point: there is no single I to be found in this swirling, dynamic composition we call me, myself, I. We are clearly composite beings. We are constantly shifting configurations of habits, impulses, creative inspirations.

This early exposition of the Buddhist mindfulness teachings gently leads us into contemplating several fundamental, existential questions:

What is our true nature?

Are we independent, solid unities as our use of the single pronoun (me) suggests?

When we look carefully, where in the body or mind do we find this core inner self?

Can we point to it?

Where is it located?

Is it in the head or the chest?

Does our sense of self grow larger when we are praised and smaller when we are criticized?

Look, then look again. The “answers” to these and similar questions are to be found in our experience.

Seeing Change Everywhere

Next, we move to consider feelings of being permanent, unchanging selves. Here the practice of mindfulness of breathing provides an ideal entrance into insight. Mindfulness of breathing is often taught as a way of cultivating steady, non-judgmental attention. Yet mindfulness is also experiencing each breath as it arises and dissolves. Mindfulness is the opposite of a “seen one breath, seen them all” approach. Through sustained practice, we discover that each breath is different, distinct, never the same. Breathing itself is a changing process as in-breath and out-breath alternate. Breathing is change. Where in this constantly flowing exchange is there an independent, permanent self? If the self is the same as breathing, then clearly what I am changes. If there is a self somewhere else, how is that self related to this pulsing, rhythmic, back-and-forth process?

Mindfulness of breathing leads directly into glimpses of impermanence: arising, being, ceasing, arising, being, ceasing. Through close attending to breathing, we are introduced again and again to change, changing, changes.

As we sit, we also notice that our feelings change. Along the way, we may hear a voice of resistance: “Okay, my body is composed of parts, and these parts are themselves changing, but the real inner me—that’s always here, right? That must be my true self, my feelings.” Mindfulness of feeling offers ample evidence to the contrary: a feeling of pleasure arises and eventually fades, then a feeling of dislike arises and also eventually dissolves. None of our feelings last forever. If they did, the feeling of pleasure would displace all other feelings, now and forevermore. In our experience, this clearly is not the case. Mindfulness of feeling reminds us of the truth of impermanence, lack of a solid, enduring inner self.

Similarly, the mindfulness of mind shows us the changing flow of discursive thoughts, sometimes like a slow river, sometimes like a rapid brook, but always moving, now accelerating, now decelerating. What we call “mind” sometimes behaves like an espresso-charged grasshopper, first landing here, then there, then elsewhere. At other times, mind is sluggish, lethargic, almost too tired to move. Using imagery from nature, meditators have described their experience of mind to be like encountering a waterfall, a geyser, an avalanche of thoughts. Our experience of mind during sitting meditation does not suggest meeting a fixed, permanent entity: “my mind.”

That which sees confusion is not itself confused. This is the revolutionary discovery of awareness.

With all this experience-based evidence from meditation and contemplation, why do we cling to the idea of being a single, permanent, independent self?

In Progressive Stages of Meditation on Emptiness, Tibetan meditation master Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso explains:

The question is not whether or not the person, personality, or ego is a changing, composite train of events conditioned by many complex factors. Any rational analysis shows us that this is the case. The question is why then do we behave emotionally as if it were lasting, single, and independent…. When looking for the self, it is important to remember it is an emotional response one is examining. Our mistaken perception is not a simple cognitive error that can be immediately and easily adjusted in the face of evidence to the contrary.

We are deeply and emotionally invested in the concepts and ideas of a solid, permanent, unitary self, even though, as Khenpo Rinpoche clarifies:

Clinging to the idea that one has a single, permanent, independent self is the root cause of all one’s suffering.

It’s All in the Mind?

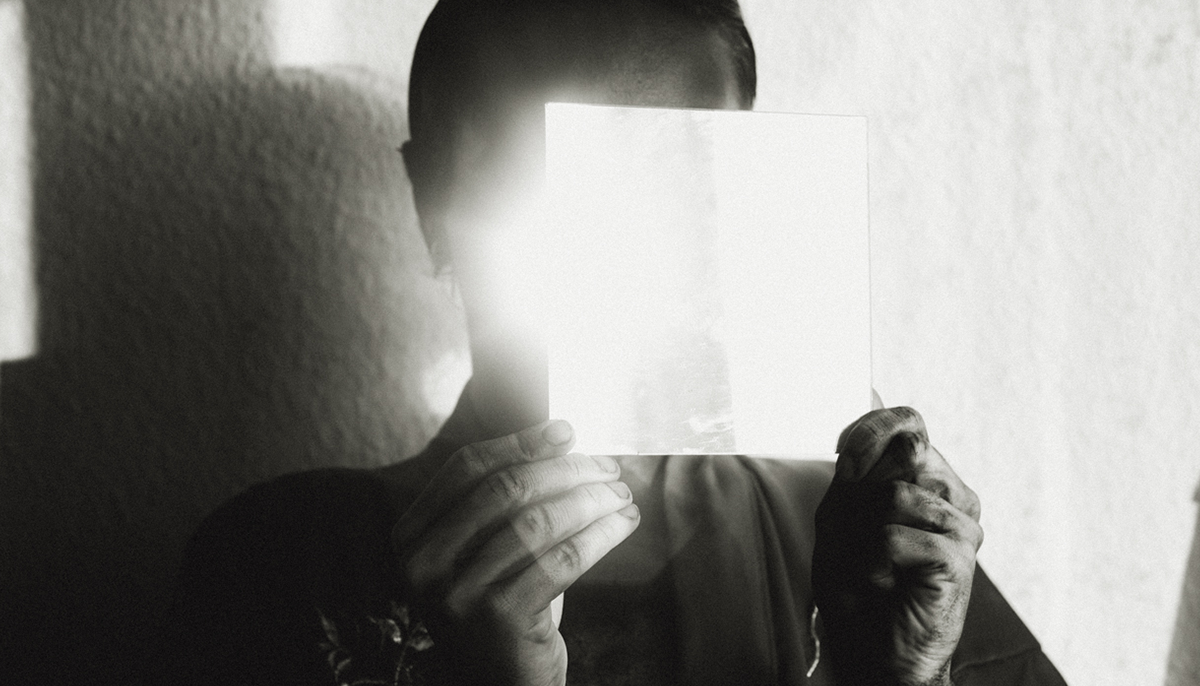

The bad news that the Buddhadharma presents us with is that we are suffering, born in suffering, living in suffering, making suffering worse by habits of denial and aggression. The good news is we have an innate capacity to see suffering clearly. That which sees confusion is not itself confused. This is the revolutionary discovery of awareness, a clear mirror in which all our experience can be seen just as it is, nothing added, nothing ignored.

We may discover awareness in the midst of cultivating mindfulness of mind. What is it that knows when the attention is with the body breathing and when attention has wandered into fantasies of the past or future? What is this clear and present knowing of our mind states? Awareness. Without this inborn capacity for accurately discerning the placement of our attention, we could not cultivate stable mindfulness at all. In the sitting practice of meditation, we discover the innate richness of jewel-like awareness. The essential importance of mind appears in all Buddhist traditions, going back to the first verses of the Dhammapada: “If the mind is clear, whatever you do or say will bring happiness that will follow you like your shadow.” In another translation: “We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts.” The teaching of the six realms of confused existence (humans, jealous gods, hungry ghosts, hell beings, animals, gods) is based on different kinds of mental states. In the traditional example, one being gazes calmly at a peaceful lake, while another being—angry and filled with hatred—sees this as a lake of raging fire burning all around. Meanwhile, hungry ghosts perceive a pond of delicious milk and honey with a thirst that can never be quenched. In each case, the determining factor is the state of mind of the perceiver. The central insight?

Mind matters.

Through the sitting practice of meditation, meditators become painfully familiar with ceaseless psychological migration through the six realms. We are like eternal hitchhikers. Intensive practice sessions often include periods of dwelling in each of the realms, perhaps for an hour, an afternoon, maybe even an entire day. Intimacy with the mind’s cycling through different mental states is another step toward realizing emptiness.

If the mind is the source of our heavens and hells, cravings and distastes, then reliable well-being cannot be found through external things and events alone. This decisively shifts the emphasis of our spiritual path from what seems to be happening “out there” to our own state of mind and being. All things are impermanent and contingent, subject to causes and conditions. Despite countless ads suggesting otherwise, there is no permanent joy to be found in getting and spending. Seeking answers outside will never bring liberation. What matters most are inner qualities of consciousness and awareness.

Consider Suzuki Roshi’s analogy of the spacious meadow as meditation instruction: “To give your sheep or cow a large, spacious meadow is the way to control him.” The sheep and cows are all temporary mind-states, mental formations. They show up in the meadow, eat some grass, chew their cud, and eventually wander off. These cows and sheep are like mental events—changing, conditioned, lacking in solidity. Trying to control them only produces more suffering.

What about the meadow? It’s not a mental event or temporary formation. The meadow seems to be an underlying ground that can spaciously accommodate all phenomena. This meadow seems an apt image for what Suzuki Roshi called “Big Mind.” Here, the meadow sounds quite similar to emptiness.

The temptation here is to solidify mind itself as an essence, a concrete thing. We may feel relieved: at last, we have arrived at some ground. We’ve found a home ground not “out there,” but “in here.” In a case such as this—when we’re getting stuck somewhere that feels like a comfy destination—engaging contemplative inquiry may be useful to gently nudge us along the path. Here, insight meditation means asking and looking at mind directly for experiential guidance:

What is awareness?

Does it reach out to the sounds I hear, or do the sounds come toward it so that they meet somewhere in the middle?

Does awareness have a shape or color?

Does it arise and cease?

Look, look again, and see.

This is a path of insight into mind’s true nature, beyond all our concepts. Mind is not a thing. It cannot be objectified. It’s never an object. As Suzuki Roshi commented, “The big mind in which we must have confidence is not something which you can experience objectively. It is something which is always with you, always on your side.” If you see mind in a small way, he goes on to say, you are “restricting your true mind, objectifying your mind.” Just as our previous insight journey showed us that forms and feelings are composed of parts, impermanent, and not solid, here we discover that mind isn’t solid either. Only our confused concepts seem to make it so.

Brilliance

Let’s return now to the Four Foundations, revisiting them this time as foundations for insight. Each is used as a basis for applying the method of contemplative inquiry. Our main questions are: What is “body”? What is “feeling”? What is “mind”? What are “sense perceptions”? The quotation marks are needed here because in each case we begin with what is called “body” and then proceed to lean toward more direct experience beyond conventional names and designations. We are gradually peeling away layers and layers of obscuring concepts.

Beginning with the body, what is it? We have scientific findings from anatomy and physiology, but that’s not the kind of knowledge we need in this case. We are inquiring into our own experience of our physical form: What is that?

Whatever arises (“my body is a material object in space with weight and volume”), we welcome that answer, and rest for a moment.

Then we ask again: What is this “material object in space” really? Receive the answer that arises gratefully, rest for a moment, then inquire again.

In this process, we are gradually leaning in the direction of meeting what Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche called “body-body.” He contrasted this with the dense conglomeration of opinions and concepts around our physical forms, which he called “psychosomatic body.” But “body-body” isn’t a final answer here either, just a way station for the next round of inquiry: What is “body-body”? Inquire, look, rest with whatever we find, then inquire again. Round and round we go.

Dropping our storyline means leaning toward our actual felt sense and texture of feeling, rather than elaborating more narratives.

Similarly, we might inquire into feeling—attracted, repulsed, neutral. What is it that we call “feeling”? Sometimes practitioners exploring desire will say: “Well, it’s an energy, a warm energy.” Good. Let’s be grateful for that insight and rest for a moment with it. Then, back to work: What is this “warm energy”? Warm energy is just a name for something. What is “warm energy” really?

This process of inquiry echoes some of the meditation instructions received from Pema Chödrön and other teachers to “drop the storyline” when intense feelings arise in meditation. Storylines about our emotions are usually either justifying (“It’s right that I feel this way. Look what they did!”) or negating (“What’s wrong with me that I feel this way, again?”). Dropping the storyline means leaning toward the actual felt sense and texture of feeling, rather than elaborating further narratives about it.

This is a more naked, direct approach to our experience.

Inquiring into the nature of mind is like walking over slippery terrain. At moments we feel there really is no “mind,” just a word we assume refers to something real and substantial. Yet experience arises, and what is that? Similarly, we may feel—as names begin to slip and slide—that there is no “body,” no “feeling,” no “consciousness.” When we inquire into sense perceptions—are they really out there or in here?—we glimpse something like no form, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch. In this way of experiential inquiry, we gradually draw closer to the luminous profundity of the Prajnaparamita Hridaya (“Heart”) Sutra.

Insight beyond the veil of words and names reveals…what?

Neither presence, nor absence, not something, not nothing, neither true existence, nor empty void. In the ninth century, Ch’an master Hsuan-sha taught, “The whole of existence is one bright pearl.” We have approached this bright pearl gradually. Yet, all along this way: no-self is emptiness; consciousness is empty of dualities; bodies, feelings, minds are all emptily, vividly as they are. In the fourteenth century, the mystic Catherine of Siena proclaimed, “All the way to heaven is heaven.”

Here, we might say: all the way to emptiness is emptiness. With each step we arrive.