Engaged Buddhism recognizes that suffering—dukkha in Buddhism—isn’t just an individual matter. Suffering is caused both by our personal actions, our karma, and by the social systems we live in and create. The individual and society are inseparable, so Buddhists who have vowed to relieve suffering must address both.

In 1964, Thich Nhat Hanh published a collection of essays entitled Engaged Buddhism. In coining this term, he was advocating that Buddhists step out from the meditation hall into the streets and fields to serve people. The essence of his Engaged Buddhism was political and social action, and such action was already evident in the visionary work of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, who led a Buddhist conversion movement of India’s Dalits; in Sri Lanka’s Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement of uplift and self-governance founded by A. T. Ariyaratne; and in the radical Buddhist critique of Sulak Sivaraksa in Thailand; and the work of others across Asia.

Unique to these movements was the integration of Buddhist teachings with Western principles of social justice. American poet Gary Snyder wrote of this integration in a 1961 essay, “Buddhist Anarchism”: “The mercy of the West has been social revolution; the mercy of the East has been individual insight into the basic self/void. We need both.”

With this view in mind, I came to Buddhist Peace Fellowship in 1991, having absorbed the seminal teachings of the elders profiled here—Thich Nhat Hanh, Robert Aitken, Joanna Macy, and Maha Ghosananda—while the excellent writings of Rev. angel Kyodo williams came a few years later. A vision of Engaged Buddhism was clear to me and my friends, but we got the message that many practitioners in the West saw Engaged Buddhism as merely leftism in Buddhist clothing. I’ve never accepted that, nor did our elders. We just bowed our heads, strengthened our backs, and pushed on.

From the beginning, the Buddha was responsive to the society of his time. Seeing how people’s lives were defined by conditions of birth, which included gender, caste, color, and occupation, he created an alternative culture, a sangha, in which a person’s worth was based on his or her actions. Such Buddhist values and culture pervaded India and surrounding countries for more than a thousand years. In a society where life was so socially determined, the Buddha offered the remedy of a radical individualism embraced and embracing community.

Today, with Western values of self-centered individualism poisoning our lives and spreading like a virus across the world, it may be that the deep social vision of Engaged Buddhism provides the remedy we search for.

—Hozan Alan Senauke

Rev. angel Kyodo williams

Williams was the first to give voice to the lived experiences of Black Buddhists, says Pamela Ayo Yetunde.

Like many other African Americans back then, I was introduced to Buddhism in 2001 through a book written by someone who was not Black. Since then, a sea change in American Buddhism and Black religion has occurred in just one generation, and I attribute much of that change to Soto Zen priest Rev. angel Kyodo williams, a living guardian angel. There must be something in a name.

Nearly two decades after rev. angel’s 2000 book Being Black: Zen and the Art of Living with Fearlessness and Grace was published, I attended one of her BIPOC retreats. There she recounted how she, and her book, were harshly criticized for not being Zen enough, because she wrote about being Black.

As I listened to her I understood that she gave all later Black Buddhist writers a special kind of black Zen cushion that protected us. She took the hit of the initial white supremacist rage that would have landed hard on the rest of us if we’d been the first to write about our lived experiences as Black Buddhists.

Rev. angel said that she then co-authored her 2016 book, Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation, because while Being Black was an open invitation to Black people, it was insufficient for white sangha transformation. Radical Dharma was needed to teach white Buddhists how to be hospitable across our racialized differences.

How many of us are willing, as Rev. angel has been, to spend two or more decades of our lives working for the liberation of Black people from racist oppression and the liberation of white sanghas from racialized ignorance? Not many. Rev. angel is a living guardian angel, a Harriet Tubman–like bodhisattva in the spirit of Samantabhadra—engaging in liberative and loving activity throughout the world, skillfully using the media as a means to get her messages and practices across the globe.

Supporting Rev. angel’s work, and receiving her blessings, has been an honor, and I’ve repeatedly incorporated her work into my scholarship. Her invitations to attend The Gathering I and II of Black dharma teachers were precious gifts. I feel that angel is on my shoulder, and I know many others also feel the sense of guardianship that can only come from someone who laid the path decades before we even knew there was a path. Thank you, angel.

Teaching: Prophetic Wisdom

Rev. angel Kyodo williams on the unconventional prophets called for in these times.

With the exception of Malcolm X, the Black prophetic voice has been erringly associated with Christianity. The prophets called for in these times necessarily arise from, to paraphrase Dr. Ibrahim Farajajé, organic (post-, trans-, and) multi-religiosity.

Prophetic wisdom, while likely drawing on the particular religious and spiritual inspiration of its conveyor, transcends dualism or any frames that would limit the creative emergence of truth. Rather than adherence to our containment by particular ideology, its starting point is that fundamental wisdom and basic goodness are inherent. As a result, it pivots away from salvation toward liberation. Not “liberation from,” which mirrors salvation, but rather “liberation for the sake of it,” which presupposes that it is always there.

Collectively, its practitioners are bound by an allegiance to what I refer to as a new dharma. It is an approach rather than a method. Dynamic, rather than static. Emergent, rather than preconceived. A how, rather than a what. It is the way in which dharma—universal truth—embedded within and across wisdom traditions, whether East, West, Indigenous, ancient, tribal, or revealed, expresses itself in this culture in this moment of time.

Dharma is a Sanskrit word meaning universal truth, teachings, that which is firm, living in accordance with natural order, among other things. The religions that have historically been associated with it date back over five thousand years. Though it should be noted that while they are often referred to as the oldest, they are practically new compared with the collective religions of ethnic indigenous peoples.

New dharma embraces the mash-up of those ancient teachings coming into contact with traditional Western religions, and earth-based spiritualties…. New dharma also integrates emerging fields of study that draw heavily across traditions, theories, methodologies, pedagogies, and practices. It is willing to embrace the revelations of new sciences while recognizing they are only revealing what has always been known by peoples and wisdoms since lost or never validated within the narrow scope of Western ontology.

Joanna Macy

For David Loy, Macy is a the ultimate ecosattva, a bodhisattva dedicated to saving the earth.

If the ecological crisis is the greatest challenge that humanity faces today, then Joanna Macy is unquestionably one the most important teachers of our time. Whenever I reflect on the path of the ecosattva—the bodhisattva dedicated to saving the earth—Joanna is the model that comes to mind.

Joanna (everyone calls her Joanna) first encountered Buddhism while working with Tibetan refugees in northern India, and later practiced in the Theravada tradition. It is no exaggeration to say that she is the founder of the ecological movement within contemporary socially engaged Buddhism.

Her work relates Buddhist principles to systems theory and to the deep ecology movement founded by Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess. She is the creator of a training now known as The Work that Reconnects to transform what she calls the “great unraveling” of our modern industrial growth society into a more sustainable and just civilization. Her most important books include World as Lover, World as Self; Coming Back to Life and her 2007 memoir Widening Circles.

Grief is a central theme in her work. Her books offer exercises that can help us deal with our despair about what is happening today, grounded in the insight that grief is an appropriate response to what we are doing to the planet and ourselves.

The Work that Reconnects offers a transformative spiral that starts with coming from gratitude, which enables us to honor our pain for the world. This is followed by seeing with new eyes, and only then by going forth to participate in what she calls The Great Turning.

Beginning with gratitude—remembering to appreciate the beautiful web of life that creates and sustains us—provides the foundation for the whole process. Instead of begrudging our fate, we can learn to cherish it.

“I feel so fortunate to be alive now,” she says. “People might think I’m crazy, but just speaking personally, it’s an incredible thing to be alive with my fellow humans at a time when the future looks so bleak…. Since the outcome is uncertain, we have to enjoy doing something exhilarating and useful without knowing for sure if it’s going to work out.”

Those of us engaged in the work of ecodharma have been inspired not only by her writings but by her personal example. An early and important activist in the anti-nuclear movement, Joanna is someone who definitely “walks the talk.” Recognizing her importance, Naropa University has established the Joanna Macy Center for Resilience and Regeneration to advance the vision and legacy of her work.

Teaching: Wonder Beyond Words

Joanna Macy on what a gift it is to be human.

We have received an inestimable gift. To be alive in this beautiful, self-organizing universe—to participate in the dance of life with senses to perceive it, lungs that breathe it, organs that draw nourishment from it—is a wonder beyond words. And it is, moreover, an extraordinary privilege to be accorded a human life, with self-reflexive consciousness that brings awareness of our own actions and the ability to make choices. It lets us choose to join the praising and healing of our world.

Gratitude for the gift of life is a primary wellspring of all religions, hallmark of the mystic, fuel for the artist. Yet we so easily take this gift for granted. That is why so many spiritual traditions begin with thanksgiving, to remind us that for all our woes and worries, our existence itself is an unearned benefaction beyond any we could merit.

In the Tibetan Buddhist path, we are asked to pause before undertaking meditative practice and reflect on the preciousness of a human life. This is not because we as humans are superior to other beings, but because we can “change the karma.” In other words, graced with self-reflexive consciousness, we are endowed with the capacity for choice—to take stock of what we are doing and change direction. We may have endured for eons of lifetimes as other life forms under the heavy hand of fate and the blind play of instinct, but now at last we are granted the ability to consider and judge and make decisions. Weaving our ever more complex neural circuits into the miracle of self-awareness, life yearned through us for the ability to know and act and speak on behalf of the larger whole. Now the time has come when we can consciously enter the dance.

In Buddhist practice, that first reflection is followed by a second, on the brevity of this precious human life: “Death is certain; the time of death is uncertain.” That reflection awakens in us the marvelous gift of the present moment—to seize this chance to be alive right now on planet Earth.

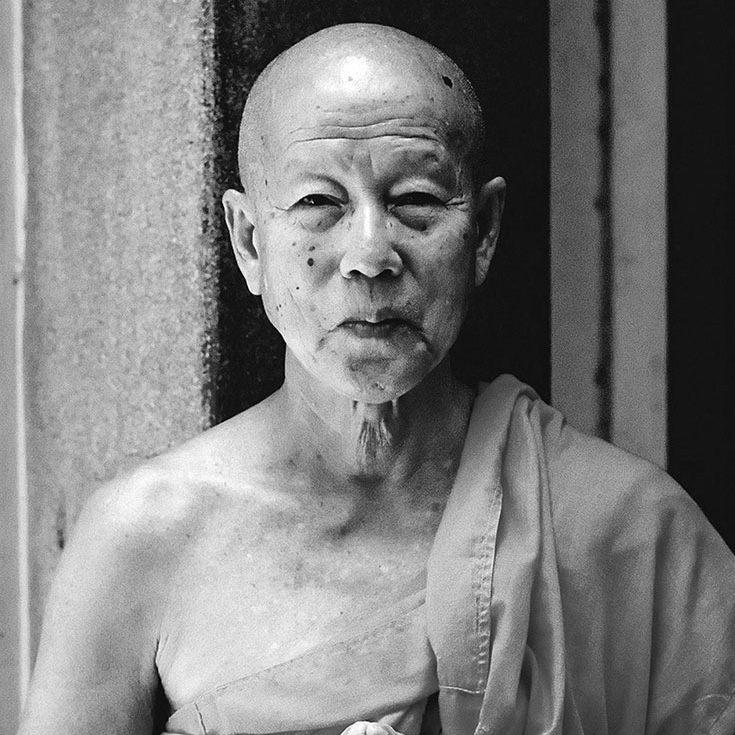

Maha Ghosananda

John A. Marston remembers the monk’s powerful gift of hope.

Maha Ghosananda is best known for leading peace walks in Cambodia in the 1990s. These walks, called the Dhammayietra, first took place following a peace agreement between the Phnom Penh government and rebel groups. The first walk, in 1992, was from refugee camps on the Thai–Cambodian border to Phnom Penh. Conceived as walking meditation, the Dhammayietra conveyed a message of hope after years of turmoil and evoked powerful emotions in participants, villagers along the way, and international observers. Working for the U.N. in Cambodia at the time, I followed reports of the walk and felt the excitement. Together with monk friends, I joined a later walk, on the last day, as it circled the city.

Maha Ghosananda was from an ethnic Chinese family in southern Cambodia. As a young monk in Phnom Penh during World War II, he had to flee by foot to his home province, sixty-five kilometers away, when his temple was bombed.

In the 1950s, Maha Ghosananda studied in Bihar, India, at Nava Nalanda Mahavihara, a newly created institute devoted to Buddhist textual studies. He had contact with an international community of monks and experienced a heady time of Indian Buddhist revival when there was much discussion of the relationship between Buddhism and progressive philosophies. He was there when B. R. Ambedkar, a major “untouchable” political figure and thinker, publicly converted to Buddhism. He also had contact with Nichidatsu Fujii’s Buddhist movement emphasizing world peace.

In the 1970s, turning away from intellectualism, Maha Ghosananda spent several years in intensive meditation in Thailand. At the end of the decade, however, when Cambodians began arriving in large numbers at the Thai border, he began visiting refugee camps. His work with Protestant clergyman and activist Peter Pond resulted in him going to the U.S. to work with newly resettled refugees, while creating, with Pond, the Inter-Religious Mission for Peace in Cambodia and the World, an organization to support activities in Cambodia and the camps. Maha Ghosananda also played a major role in establishing Cambodian temples throughout the U.S. He was a founding member of the International Network for Engaged Buddhists and a regular presence at the international negotiations leading to 1991 Cambodian peace accords.

My appreciation of Maha Ghosananda has evolved over the years. As an academic working on Cambodia, I always understood his historical importance. Over time, I’ve come to understand the depth of his spirituality—how profoundly he’d absorbed, as a Buddhist, concepts such as dukka, metta, and peace, and how, drawing on that base, he’d chosen to act for social good. Z

Teaching: Dharma 24-7

The dharma is timeless, says Maha Ghosananda, because it’s always true.

Life is filled with eating and drinking through our senses, and life is also keeping from being eaten. What eats us? Time! What is time? Time is living in the past or living in the future, feeding on the emotions. Beings who have been truly mentally healthy for even one minute are rare. Most of us suffer from clinging to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral feelings, and from hunger and thirst. We eat and drink every second through our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, skin, and nerves, twenty-four hours a day without stopping! We crave food for the body, food for feeling, food for volitional action, and food for rebirth. We are the world, and we eat the world.

When he saw the endless cycle of suffering, the Buddha cried. The fly eats the flower; the frog eats the fly; the snake eats the frog; the bird eats the snake; the tiger eats the bird; the hunter kills the tiger; the tiger’s body becomes swollen; flies come and eat the tiger’s corpse; the flies lay eggs in the corpse; the eggs become more flies; and the flies eat the flowers.

The Dharma is good in the beginning, good in the middle, and good in the end. Good in the beginning is the goodness of the moral precepts—not to kill, steal, commit adultery, tell lies, or take intoxicants. Good in the middle is concentration. Good in the end is wisdom and nirvana. The Dharma is visible here and now. It is always in the present, the omnipresent. The Dharma is timeless. It offers results at once.

In Buddhism, there are three yanas, or vehicles, and none is higher or better than any other. All three carry the same Dharma. There is a fourth vehicle that is even more complete, called Dharmayana. It is the universe itself, and it includes every way that leads to peace and loving-kindness. Dharmayana can never be sectarian. It can never divide us from any of our brothers or sisters.

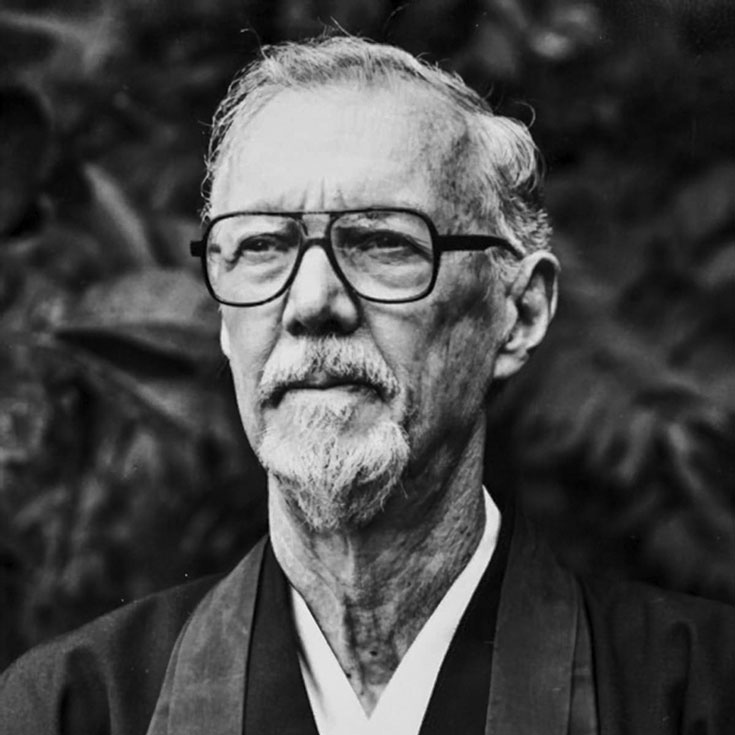

Robert Aitken

The Zen teacher was a dedicated ally to LGBTQI+ and BIPOC communities, says Butterfly (Tony Pham).

Robert Baker Aitken, a roshi who received dharma transmission from Koun Yamada and lived as a layperson, continues to teach us what socially engaged Buddhism can look like in the West. As a member of the board of directors of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF), which was cofounded by Aitken, I am honored to continue the work of engaging with how Buddhism meets and nourishes social justice movements to advance peace and freedom.

A cofounder of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha, Aitken removed a lot of the patriarchal language from the Zen tradition. In his books, Aitken offered Buddhist teachings that hold non-violence in the highest regard. He understood that those in power shape narrative context, and he demonstrated how pacifism applies to actions and words.

As someone who identifies as queer, I’m thankful for Aitken’s application of compassion toward equal rights for the LGBTQI+ community. In 1995, Aitken provided written testimony in support of marriage equality to Hawaii’s Commission on Sexual Orientation and the Law as the state was considering a same-sex marriage bill. Sharing the truth from his heart-mind, he wrote, “I find compassion—not just for—but with the gay or lesbian couple who wish to confirm their love in a legal marriage.” And he closed by saying, “I urge you to advise the Legislature and the people of Hawai’i that legalizing gay and lesbian marriages will be humane and in keeping with perennial principles of decency.”

As someone of Vietnamese descent, I respect that Aitken spoke out against the war that the United States government waged in Vietnam. He provided counseling to conscientious objectors during the draft and helped to organize the Hawaii chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. Building upon the contributions of Aitken and others, BPF co-sponsored some of Thich Nhat Hanh’s first visits to the U.S. To this day, BPF continues to be in solidarity with imprisoned Buddhists in Vietnam and around the world.

The board of Buddhist Peace Fellowship is now majority BIPOC with female and queer leadership. Like prior generations of BPF stewards including Aitken, Mushim Ikeda, Jack Kornfield, Joanna Macy, Alan Senauke, and others, we’re finding that getting to the other shore involves crossing muddy waters. Through this challenging work, we aspire to bring Buddhist perspectives of compassion, interdependence, and nonduality to contemporary social action and environmental movements.

Each time we feel challenged by the paradoxes and tensions of allowing our hearts to fully break in response to injustice, we’re inspired by Aitken’s commitment to hold the complexities of the human experience with humble tenderness.

Teaching: Zen Master Raven

A selection of Robert Aitken’s playful koans about a wise old bird.

Essential Nature

Early one morning Woodpecker flew in for a special meeting with Raven and asked, “I’ve heard about essential nature, but I’m not sure what it is. Is it something that can be destroyed?”

Raven said, “That’s really a presumptuous question.”

Woodpecker ruffled her feathers a little and asked, “You mean I shouldn’t question the matter?”

Raven said, “You presume there is one.”

Maintenance

Mallard attended meetings for a while before asking her first question: “Aren’t we wasting time just sitting here while the Blue Planet goes to hell?”

Raven asked, “Do you waste your time eating?”

“Is that all it is,” Mallard asked, “just personal maintenance?”

Raven said, “Mallard maintenance, lake maintenance, juniper maintenance, deer maintenance.”

Death

Mole came to Raven privately and said, “We haven’t talked about death very much. I’m not concerned about where I will go, but watching so many family members die, I’m wondering what happens at the point of death?”

Raven sat silently for a while, then said, “I give away my belongings.”

Very Special

In a group munching grubs one afternoon, Mole remarked, “The Buddha Shakyamuni was very special, wasn’t he! I’m sure there has never been anyone like him.”

Raven said, “Like the madrone.”

Mole asked, “How is the madrone unique?”

Raven said, “Every madrone leaf.”

Mole fell silent.

Porcupine asked, “How does the uniqueness of every madrone leaf relate to the practice?”

Raven said, “Your practice.”

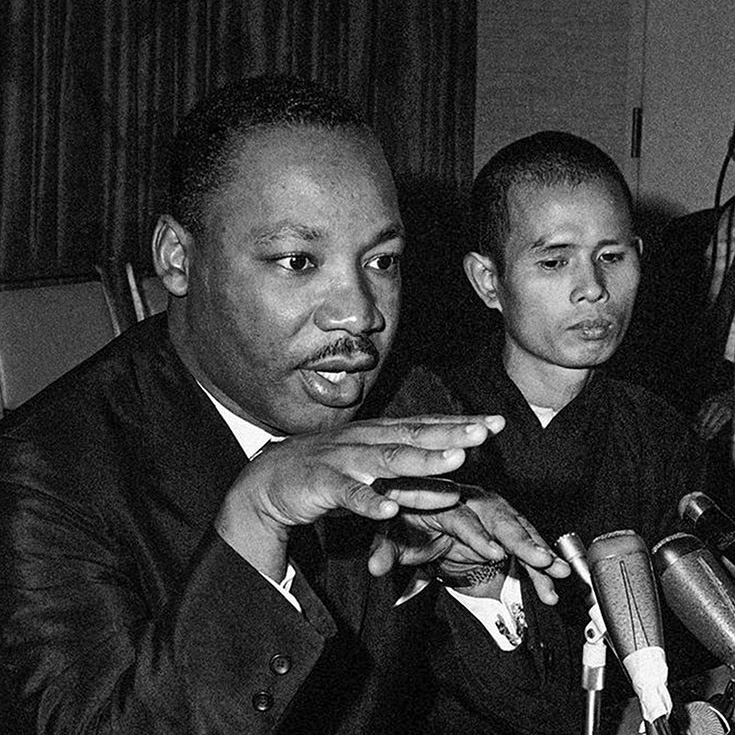

Thich Nhat Hanh

Roshi Joan Halifax on the Buddhist monk who showed her there’s no way to peace. Peace is the way.

The war in Vietnam was raging, and so were many of us young Americans. We were meeting a frontier of consciousness that focused on freedom, the environment, justice, and nonviolence. Yet for many of us, our sense of moral outrage toward the government was anything but nonviolent.

In the midst of this wild psychosocial tangle arrived a young Buddhist monk, who travelled from France to the United States to urge our country to stop bombing his country, Vietnam. His name was Thich Nhat Hanh. During his time in New York City, he joined a vast peace march down Fifth Avenue where, I recall, he did something very curious. While thousands pressed forward anxiously and quickly, he walked extremely slowly and mindfully, causing great consternation to the police and to the many people who did not understand what he was doing.

It was at this strange moment that I realized being a social activist was not necessarily separate from being a contemplative. My mind and heart changed, and my life as well. That day—because of him—many of us opened our lives to the path of socially engaged Buddhism.

Thich Nhat Hanh was for me the model of an Engaged Buddhist, but it was another twenty years before I met him personally. In the mid-eighties, I found myself at his monastery in France, sitting in a small stone building with him and his colleague Sister Chan Khong. I vividly remember the meal we shared: white rice and mustard greens. We ate so silently I could hear the inner workings of the clock hanging on the rough plaster wall. I was eating quickly, but then I realized that Thay, as his students affectionately call him, was chewing his rice many times. I slowed down.

When I finished my meal, I thought that was that. But Thay looked into my bowl, and following his gaze, I realized five small grains of rice were left at the bottom. Thay looked at me with a straight face and said: “You did not finish your rice. It seems that you will be reborn as a duck.” I burst out laughing, and the merriment on his and Sister Chan Khong’s faces lit up that tiny, dark room.

I became Thay’s student. His teachings on social engagement, direct and indirect, will continue with me the rest of my life. As for being reborn as a duck, I have since that time tried to be scrupulous about finishing my meals.

Teaching: Peace Begins with You

If you want to change the world, says Thich Nhat Hanh, start with your own mind.

We need a real awakening, a real enlightenment. New laws and policies are not enough. We need to change our way of thinking and seeing things. This is possible; the truth is that we have not really tried to do it yet. Each one of us has to do it for ourselves. No one else can do it for you. If you are an activist and you’re eager to do something, you should begin with yourself and your own mind.

It’s my conviction that we cannot change the world if we’re not able to change our way of thinking, our consciousness.

Collective change in our way of thinking and seeing things is crucial. Without it, we cannot expect the world to change.

Collective awakening is made of individual awakening. You have to wake yourself up first, and then those around you have a chance. When we ourselves suffer less we can be more helpful and we can help others to change themselves too. Peace, awakening, enlightenment always begin with you. You are the one you need to count on.

On the one hand, we must learn the art of happiness: how to be truly present for life, so we can get the nourishment and healing we need. On the other hand, we must learn the art of suffering: the way to suffer, so we suffer much less and can help others suffer less. It takes courage and love to come back to ourselves to take care of the suffering, fear, and despair inside.

To meditate is crucial, to get out of despair, to get the insight of non-fear, to keep your compassion alive so you can be a real instrument of the Earth, helping all beings. To meditate doesn’t mean to escape life, but to take time to look deeply. You allow yourself time to sit, to walk—not doing anything, just looking deeply into the situation and into your own mind.