He played and wrote for Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet, and fusion supergroup Weather Report. He was John Coltrane’s jamming partner, later became Joni Mitchell’s key collaborator, and played that blazing solo on the title track of Steely Dan’s Aja. By last year, he had racked up twenty-five solo releases, including landmarks like 1965’s Speak No Evil and, thirty years later, High Life. In December 2018, he was feted as a 2018 Kennedy Center honoree (along with fellow Buddhist and musician Philip Glass), and this year will see the release of the documentary Wayne Shorter: Zero Gravity.

If anyone could rest on their laurels, it would be him.

But that’s not the way of Wayne Shorter, a creator and communicator so unconventional that even as a fledgling bebop player in the 1950s, he was known among his peers as “Mr. Weird.” Being unusual works for him.

So it’s no big surprise that, instead of just another new album, he’s released a triple album. And it comes with a graphic novel. Which he helped write.

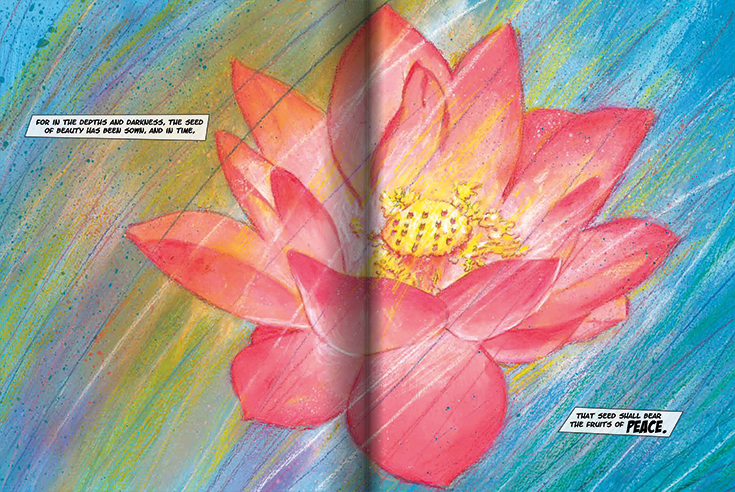

Titled Emanon—“no name,” backwards, in homage to a Dizzy Gillespie song—the physical-only release is a sprawling, lively work that marries jazz and classical instrumentation, showcasing Shorter’s considerable gifts for improvisation and composition. If it isn’t a masterwork, I don’t know what is. And that’s not just me: Emanon has received rave reviews from NPR, Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and on and on. And at the center of it all is a Buddhist superhero of sorts.

Emanon’s origin story isn’t as thrilling as you’d hope with a creation of this magnitude. “We were going to make a record,” Shorter tells me, “and Blue Note Records president Don Was said, ‘Why don’t we put a graphic novel with it?’”

A gimmick, maybe, but Was surely knew that his idea was a perfect fit for a lifelong comics nut like Shorter, who’d even written and drawn a full comic book back when he was a fifteen-year-old kid in Newark. But this time he would have help—from screenwriter Monica Sly and veteran comics artist Randy DuBurke.

The graphic novel tells the tale of Emanon, a “rogue philosopher” who vanquishes supposed foes not through violence but by telepathically creating and conveying a sense of oneness with them. He does this not just on his home planet, but across time and space. In each new place he visits, from an alternate Earth where “men and women have no conception of a free society,” to other worlds “based on doctrines of submission and obedience,” Emanon only becomes more fearless and dedicated in his work to lead beings, human or otherwise, toward liberation and hope.

The character’s talent for multiverse-hopping has up-to-the-moment sci-fi cachet, but it also feels like something more. Perhaps it’s Shorter’s device to help us get our minds around the notion of emptiness. (That’s not an easy concept to nutshell, but this passage by the Zen teacher Dainin Katagiri is a fine start: “Most people misunderstand emptiness, thinking it means to destroy, or to ignore, our existence. This is a big mistake. Emptiness is not negative. Emptiness is letting go of fixed ideas you have had in order to go beyond them.”) Is that what Shorter had in mind?

“Yeah,” he concedes, even suggesting that his rogue philosopher is a corollary to the Buddha himself. But there’s also a classic comic-book function in play: big dreaming. Emanon, Shorter says, “kind of takes the reader and the listener into a place where they begin to wonder about their life—the days and weeks—and about being afraid. They begin to think about taking chances, and then start to take action.

“If a kid wants to be like Superman, a grownup might want to be like Emanon, you know?”

Emanon Origin Story, Take 2

It all started, in a way, because of bassist Buster Williams. It was in 1972, and he was onstage holding things down, as he always did, providing the bottom end for Mwandishi, the jazz/funk/world hybrid led by Herbie Hancock. But then Williams took a solo that Hancock would never forget.

“I was hearing notes fly all over the place, and wondering how in the world he could do all that on a four-stringed instrument,” the bandleader recalls in his memoir, Possibilities. Having heard that Williams was “into some new philosophy or something,” he asked the bassist to let him in on whatever secret had set his creativity so free. Williams was only too happy to oblige.

Williams’ “secret” was that he’d taken up Nichiren Buddhism, and its central practice of chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the title (or daimoku) of the Lotus Sutra. Founder Nichiren Daishonin (1222–1282) had insisted that the Lotus Sutra was the Buddha’s highest teaching, and the daimoku its distillation. By steadfastly chanting it, practitioners could realize its wisdom in their lives.

All my walls came down. What happened to me was a letting go of false thinking. False to myself.

Just as Williams had, Hancock passed the practice on, this time to Ana Maria Shorter, the wife of his buddy and fellow Davis alumnus, Wayne Shorter.

“I saw Herbie and Ana Maria putting a box on the wall,” Shorter remembers. “I said, ‘What’re you doing?’ And they said, ‘Oh, we have something this Buddhist monk says opens you up.’” The box was a Nichiren Buddhist shrine, which contains the Gohonzon, a scroll and object of devotion to be faced while chanting.

Ana Maria Shorter dove in, chanting regularly. Wayne Shorter, a lover of sound if ever there was one, enjoyed hearing the chant as it sounded through their home, but mostly stayed at a safe remove, only dabbling now and then.

“Time goes by, maybe three or six months,” Shorter remembers. “I saw my wife going to practice, and I sat beside her and said, ‘Show me what you’re doing.’ Because by now Ana Maria and Herbie had said to me, ‘Why don’t you try it out for your daughter’s sake?’”

That daughter, Iska, had been born in 1969, when Shorter was forty. Deeply, unquestionably loved, Iska nonetheless represented a challenge: having sustained brain damage just weeks after her birth, she required a high degree of medical and parental attention. Helping Ana Maria Shorter ground herself had, in fact, been why Hancock introduced her to the practice.

Wayne Shorter increasingly saw the practice was helping his wife—and now he was being cajoled into trying it, with Iska in mind.

“That nailed it,” he says. “All my walls came down. What happened to me was a letting go of false thinking. False to myself. Or misleading, let’s put it that way.” Still, he remained uncommitted.

The next year, though, Shorter found himself in Japan on tour with Weather Report, the game-changing jazz–fusion outfit he’d founded with pianist Joe Zawinul. There—again, thanks to his wife and Hancock’s intervention—Shorter met drummer and Nichiren practitioner Nobu Urushiyama, who took Shorter to his family’s home for three days of R & R, which happened to include a deep dive into Buddhist texts. Suddenly feeling all in, Shorter let Urushiyama take him to a temple outside Tokyo, where he formally became a Nichiren practitioner, and the two proceeded to an event featuring Daisaku Ikeda, leader of the modern Nichiren organization, Soka Gakkai International. Ikeda and Shorter’s eyes met, and there was a knowing, a familiarity there. As Michelle Mercer recounts in her terrific Shorter biography, Footprints, it had been like “Ikeda was saying, I know what I’m going to do. I know what you’re going to do. So let’s do it together.”

All these years later, Hancock and Shorter remain collaborators, most recently as co-authors of the inspiring manifesto “To the Next Generation of Artists,” collected in Lion’s Roar’s best-of publication Awaken Your Heart & Mind. So too do Shorter and Ikeda, promoting Nichiren Buddhism and, with Hancock, releasing the book Reaching Beyond: Improvisations on Jazz, Buddhism, and a Joyful Life.

Shorter credits Soka Gakkai International (SGI) and Ikeda with having a tremendous influence in his life, but when I suggest that that influence runs on a two-way street—because he’s been a high-profile ambassador for Nichiren Buddhism since his very start with it—he’s almost too humble: “I think the thing I’ve contributed to SGI is not giving up.”

“Awake, Awake”

Much is made, when people talk about SGI, about the idea that its practitioners chant “for material gain.” Indeed, initiates are often told that if they would like to chant with the motivation of improving their circumstances, that’s fine: a better job, better health, a new car, even straight-up money and fame. But that’s not the whole story, and Shorter is happy to fill in some blanks.

“When I talk to people out there, I tell them: this money, the fame, they’re teachers. These things are supposed to teach us something.” Chanters might start small, practicing with a “localized” motivation (often, themselves), but if they persevere, their vision and motivation can expand over time: the wish for a better “me” evolves into a wish to connect with others, to be of benefit to them, and to not miss the constant stream of opportunity that life throws at us.

“I think everything around us, even the most devastating things, is saying, ‘Awake, awake,’” Shorter tells me. “And this awakening is done through our actions.”

He’s seen it manifest in others: “I’ve met people who were self-destructing and then fifteen years later, after practicing this practice, the self-destructing is not there any longer. I’m talking about people who were without meaning, who were on that real road to destruction, through addiction and alcohol and all kinds of stuff like that. It’s amazing.”

Shorter’s had his share of similar struggles. “In the army,” Shorter says (he began his two years of service in 1958), “every weekend at someone’s house, we had parties. And when I got out and started working in New York, working in nightclubs, there was a lot of alcohol. You play and you go down to the bar and you buy everybody a drink. It’s like a big party all the time.” But Shorter’s drinking became more frequent, less social. A problem.

Before beginning his Buddhist practice, “My attitude about life was, I have my own philosophy [Laughter]. I thought, I know where I’m going.” But Shorter would find a new philosophy and, with it, clarity. Drinking began to lose its power, and his practice and creativity blossomed. “From that point,” he says, “I started to think about getting my own band.”

He’d also, in 1977, become a collaborator of Joni Mitchell, after the two met through Weather Report’s phenomenal bassist, Jaco Pastorius. Starting work on Mitchell’s Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter LP, Mitchell and Shorter immediately impressed each other with their sophisticated yet free approach to music making. And they shared a worldview: “At twenty-one, I already was beginning to conceive of the concept that perhaps life is somewhat of an illusion,” Mitchell has said. “Which is kind of a Buddhist idea. Wayne and I are both Buddhists.” They would continue to work together, taking advantage of their easy rapport through the release of Mitchell’s penultimate studio album, 2002’s Travelogue.

For much of that time, Shorter’s dream of having his own band went unrealized. Having started Weather Report in 1970—and going on to create thirteen studio albums with them, including 1977’s megahit, Heavy Weather—Shorter parted ways with Zawinul in 1985. He would still tour, and record with Mitchell when the chance arose, but the eighties had brought with them some heavy losses: the death of Iska in 1983 after a grand mal seizure at age fourteen, and, in 1986, both the death of Shorter’s mother and his separation from Ana Maria Shorter—who would herself pass, along with their niece, in an airplane explosion ten years later. (Shorter later married Carolina Dos Santos, a dear friend of his ex-wife, and the couple remains together today.) His brother, Alan, also a jazz musician and composer, died in 1988. It was to be a period of relative creative quiet, with Shorter taking a seven-year hiatus from releasing solo LPs.

That ended with 1995’s High Life, a more synthesized outing than some might have expected, but being unusual worked again: High Life earned Shorter a Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Album.

In 2000, he hooked up with pianist Danilo Pérez, drummer Brian Blade, and bassist John Patitucci to form a new quartet. They’ve been going ever since, and their chemistry is palpable throughout Emanon’s three discs. Though Shorter is the group’s compositional force, improvisation, even democracy, are at the fore in this band, he says. “We don’t rehearse. When we get together, we talk to each other, but we only talk of playing. Then, after playing a while, we’ll say, ‘Where did that come from?’ And when one soloist interrupts another soloist, it’s not an interruption, it’s an opportunity. The ears grow with all you hear. We can hear and not just anticipate.”

I ask Shorter if this ability to tune into musical opportunity is informed by his Buddhist practice. “Oh yeah,” he confirms, and then notes how his musical “compadres” react to his seemingly endless energy, which he presumably chalks up to practice as well. “When it’s time to leave the hotel, and I’m up early, they’re saying, ‘How do you do that?’ And they’re much younger than me!”

Since Emanon’s first disc features the band playing with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, you might expect improvisation to suffer. But not on Shorter’s watch. “When you get classical musicians together with people who improvise,” he tells me, “it’s more than music. A lot of jazz musicians used to say that classical doesn’t swing. So, you think you’re going to rehearse and make them swing so they can sit with you.

“It hit me in the head—here’s the Buddhist practice again—and I said, they shouldn’t change the way they play. They should just do what they’ve been doing, and we navigate and work with them. If it’s easy, there’s something wrong. We want it to be difficult so we can keep breaking down any chance of arrogance during rehearsals, before we even play.”

Given its deluxe presentation, Emanon feels monumental, to me at least. But does it feel that way to Shorter?

“Yeah,” he allows. But, he adds, in his typically big-minded but arrogance-free manner, his way is to “move on with the great adventure of everything that eternity has to offer.” He is, in fact, already on to the next thing—an opera, which he’s writing with jazz bassist and composer Esperanza Spalding.

Why an opera?

“I have some books on opera,” Shorter replies, “and one of them says, on the first page, ‘In opera, everything goes.’”