There is much to say about J.D. Salinger. He was a groundbreaker, he was reclusive, he was complex, he was unquestioningly talented and influential, and on and on; much of it true, plenty of it colored by myth. (And as a couple of readers have noted, there’s a darkness that shouldn’t overlooked, as it was by me when I first published this story a couple of days ago: Salinger has been credibly accused of alleged abuses.)

We can’t know the whole Salinger story. But we’ll have a lot more to chew on thanks to the New York Public Library’s just-opened retrospective/exhibit about the author behind The Catcher In the Rye and — truly — so much more than that book. Catcher may be his most famous work, but Salinger did take care to make his later writings go beyond.

The brooding Holden Caulfield is Salinger’s most famous creation, but the author’s heart seemed to reside with the Glass family, through which he weaved the fictional and autobiographical, projecting some version of his life/mind as refracted through the family’s characters. Which one was Salinger? The better question may be, which weren’t?

The exhibit seems like confirmation that Salinger was, at least on some level, dedicated to expanding his mind and heart.

It was through Zooey Glass — he of Salinger’s 1957 novella, Zooey, later packaged with 1955’s “Franny,” as Franny & Zooey in 1961 — that I first really encountered the idea of the bodhisattva, the aspirant who vows to save all beings, forgoing their own enlightenment and working for that of everyone else. That was in the 1980s; I was probably fifteen. And certainly not unique: the number of people who’d had the same introduction (many also as younger readers) was already incalculable just years after Franny & Zooey’s release. Salinger had become a big deal, fast. Suddenly, the bodhisattva had gotten a pop-culture boost.

The NYPL exhibit gives us a peek into the author’s own aspirational mind. As this excellent New York Times piece notes,

Some [exhibit] items give new insights into Salinger’s creative process. Others offer a rare window into his private life. There are notebooks where he jotted down passages from spiritual texts he was studying. There are shelves of books that he kept in his bedroom at the end of his life because he wanted them to be close at hand: titles about Eastern medicine and acupuncture; books by Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Michael Gilbert, Ivan Turgenev, Penelope Fitzgerald and Anton Chekhov; and spiritual tomes from Hindu, Taoist, Christian Science and Zen Buddhist traditions.

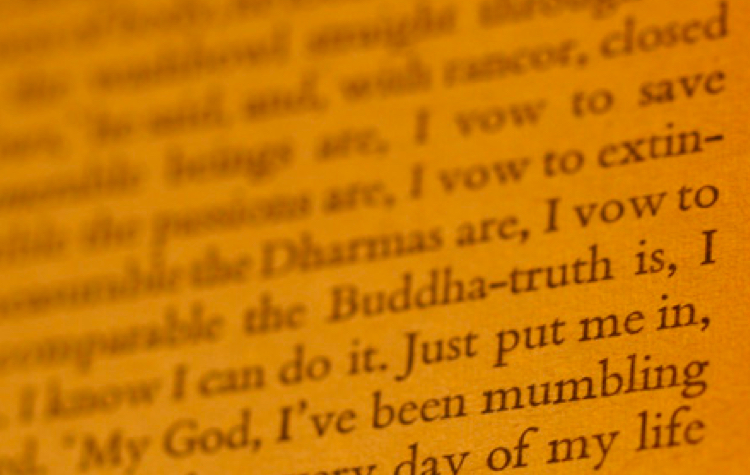

And visitors of the exhibit (and of that Times link) will see, too, Salinger’s own spiritual writings, in the form of his journals. The text we see on one open page includes what appears to be Salinger’s own typed copying, for his own record, of a Zen text:

Huang Po, p. 65**

The Elder Wei Ming climbed to the summit of the Ta Yu mountains to visit the Sixth Patriarch. The latter asked him why he had come. Was it for the robe or for the Dharma? The Elder Wei Ming answered that he had not come for the robe, but only for the Dharma; whereupon, the Sixth Patriarch said: “Perhaps you will concentrate your thoughts for a moment and avoid thinking in terms of good or evil.” Ming did as he was told, and the Sixth Patriarch continued: “While you are not thinking of good and not thinking of evil, return to what you were before your father and mother were born.” Even as the words were spoken, Ming arrived at a sudden tacit understanding.

As for the rest of us? We may never have a true understanding of the person who was compelled to dutifully re-type those words, but it’s exciting to have further confirmation that Salinger was at least on some level dedicated — maybe even Zooey-like — to expanding his mind and heart. That said, we would still do well, when assessing Salinger, to remember his abuse accuser Joyce Maynard’s admonition, that “There is art, and there are artists. Let’s not confuse the two.”

The NYPL says about the exhibit that it’s “a rare glimpse into the life and work of author J.D. Salinger with an exhibition of manuscripts, letters, photographs, books, and personal effects drawn exclusively from Salinger’s archive. This will be the first time these items — on loan from the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust — have ever been shared with the public.” The exhibit runs through January; get more details here.

** A quick look confirms that the passage Salinger was moved to retype can be found on page 65 of The Zen Teaching of Huang Po, as rendered into English by John Blofeld and first published in 1958 by Grove Press.