Dr. R. B. R. Ambedkar, a so-called “untouchable” by birth and later the first law minister in Independent India, was the architect of India’s constitution in the Nehru government. Perhaps one of the most remarkable geniuses of his time in India, he saw clearly that while you can change things in writing, doing so has little relevance in practice. He turned to religion to explore the emancipation of his people because he realized that all caste was a state of mind, a notion, and therefore that the role of religion must be to emancipate the mind. Buddhism was his answer. He went on to conduct mass conversions, bringing hundreds of thousands of “untouchables” into Buddhism and out of the caste system into which they’d been born. He knew liberation, for his people, was freedom from systemic oppression. In turning the wheel of dharma, he also revolutionized it.

When he died, however, the Buddhist world did not rally to support his work or the people who had joined him in his cause, instead labeling what he had done as “political conversion.” But how can one separate the political from the personal? From the spiritual?

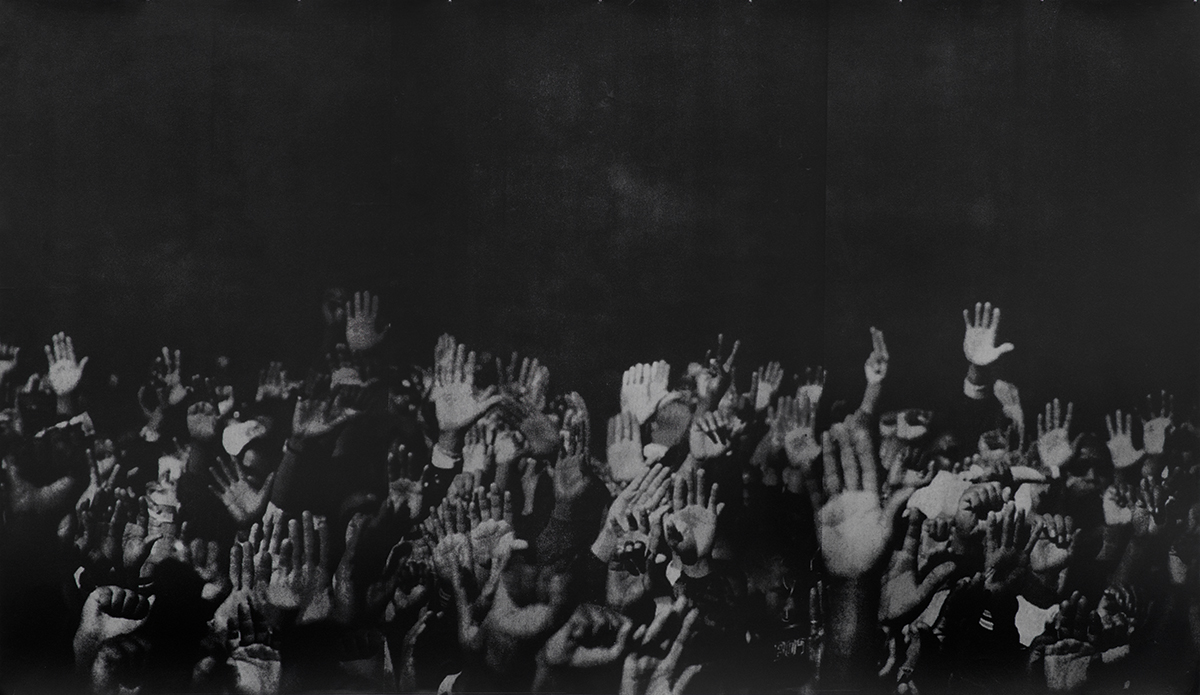

Black bodies being disproportionally killed by the police, of historical, institutional, and systemic racism — all are finally part of the conversation as integral to a Black person’s liberation, both spiritual and otherwise.

Ambedkar modified the Buddhist tradition to help it directly meet the needs of his own community, the people in India who were the most oppressed. He challenged the second noble truth by stating that suffering was not always due to craving. He asked, “But might there be circumstances in which there are innocent victims? There are children or whole communities who are marginalized and oppressed by social, political, and economic forces that are essentially beyond their control, unless they somehow collectively organize a resistance to oppression. Can Bud-dhism encompass the notion of social change, which has both victims and op-pressors?” He also challenged the doctrine of rebirth, seeing it as an unacceptable explanation for birth into “untouchable” status. His slogan, “Educate, agitate, and organize,” is still used by Ambedkarite Buddhists today.

I believe the time has come for a similar movement in the West—informed by the confidence and courage of Ambedkar, but this time, a movement of those of Black and African descent. Sixty-five years after Ambedkar’s death, conditions are once again ripe for Buddhism to take a new shape and offer strength and community to people born into oppression. We can also take note of the Dalit Panthers, a group that arose out of the Ambedkarite movement in the seventies to fight caste discrimination. The Dalit Panthers took inspiration from the Black Panthers; perhaps we, as Black sanghas in the West, can seek inspiration from Dalit sanghas in India.

In the Black churches of the US, the UK, and Canada, one often hears sermons encouraging people to vote or teaching how to work with microaggressions. Yet in dharma halls, we are still told there cannot be statements like “Black Lives Matter” on the center’s website because it is “too political.”

That is a misunderstanding. The Buddha himself advised kings. He made political statements. He was born at a time when casteism permeated much of Indian culture, when only the Brahmins, warriors, and merchants had access to the sacred teachings. The vast majority of the Indian population—the workers and the “untouchables”—would have had molten lead poured into their ears if caught listening to the teachings, or their tongue cut out if heard reciting holy scripture. So when the Buddha taught that one’s worth is not determined by their birth, he was making a political stand. He made it clear that anyone could have access to the dharma, to the holy teachings. When there was resistance from male monks against women joining the sangha, he listened to both sides and ultimately declared that women could be ordained. He also commented on political issues of the time, speaking out against evildoers, people unlawfully attacking and killing people. He did not stay separate. These were choices with political weight.

Professor Rima Vesely-Flad, in a talk titled “The Emergence of Black Buddhism in the US,” referred to three distinct areas of focus within Black Buddhism: healing intergenerational trauma, practicing devotional ancestral rituals, and reclaiming the Black body—which has been defiled and reviled—as a vehicle for liberation. This emergence is already underway. In 2021, Black sanghas are forming online and turning the wheel of the dharma by integrating the political with the personal. In those virtual spaces, discussions of Buddhist teachings include issues of the Black body under surveillance, of Black bodies being disproportionally killed by the police, of historical, institutional, and systemic racism—all are finally part of the conversation as integral to a Black person’s liberation, both spiritual and otherwise. This becomes possible only when we have Black-only spaces in which to heal.

Any discussion of Black Buddhist sanghas should begin by pointing out the difficulty of even defining “Black.” Black African, from the continent, Black African from the diaspora, Black Australian Aboriginal, Black Maori, Black Pacific Islander, Black tribals from India—the list goes on. The common denominator is that many of us descend from slaves, or from families who were torn apart through slavery (recognizing that the African American experience of enslavement was different from that of African Canadians or those in the UK).

It is also important to acknowledge that the Black sangha is not necessarily a novel concept. Asking if the time has come for all-Black sanghas assumes that within the entire continent of Africa, or in the entire diaspora, sanghas with only Black people do not already exist. But they do. Bhante Buddharakkhita, for example, has a flourishing sangha in Uganda and ambitions to train fifty-four novices, one for every country in the continent.

The emergence I want to talk about, then, is one taking place in the US, Canada, and the UK, where Black people have almost always been the minority in Buddhist sanghas. There are exceptions—Soka Gakkai, based on the teachings of the thirteenth-century Japanese priest Nichiren, has famously been much more inclusive of Black people than other groups. But that exception only proves the rule. In much of the Buddhist world outside Soka Gakkai, Black people are nearly invisible.

Elizabeth Mpyisi, a mitra (or “friend”) in the Triratna Buddhist tradition and a trustee of the Parliament Mindfulness Initiatives in the UK, advises that before we embark on Black-only sanghas, we should ask ourselves three questions:

1. What is the added value? What do we get from an all-Black sangha that is missing in a mixed sangha?

2. Do we have the resources, commitment, and uniformity of purpose necessary to sustain such sanghas?

3. Why? What is the underlying justification for practicing in an all-Black space, not just for ourselves but for the world?

I suspect anyone who has attended a Black-only Buddhist gathering can answer the first question. Konda Mason, one of the organizers of the Black African Buddhist Dharma Teachers Association (BABDTA), describes being part of one of the first Black-only dharma teachers’ gatherings as having its own “unique flavor to it, one that nourishes in a soulful way that I have never experienced. The richness is incomparable. That kind of richness—when you add the dharma and the wisdom to our culture—brings a depth of practice. On the flipside of suffering, there is a deep joy of being Black.”

The director of the UK-based Mindfulness Network for People of Colour (MNPC), William Fley, agrees. “Black sanghas,” he says, “remind us that we of African heritage can find our highest potential and re-humanization, long forgotten, to be compassionate beings.” He believes that it is by practicing within this context that we can rise above our obstructions and delusions, and in doing so, not replicate the harm and oppression bestowed to us.

For many Black practitioners practicing in spaces where they are a minority, our blackness is downplayed, our specific concerns diminished. When I came to the dharma, it was my therapy. I was told clearly by white teachers that Buddhism is not therapy—but why? The oldest therapeutic model is the abhidharma; Buddhism, for centuries, has delineated all the mental states we as humans can be confronted with. In my case, I had to free myself from the mental slavery that Bob Marley sang about—that’s what I was looking for, so that became my doorway to the dharma, as it is for many Black practitioners. If we can make space for that kind of searching—if we can just stay—then eventually, the dharma will open other doors as well.

Just in the last few years, Black teachers have begun to network and gather, sharing with each other how they share the dharma. And during the past eighteen months, Black and Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) affinity groups—in the context of twelve-step communities, Buddhist recovery communities, Buddhism and mindfulness communities, and more—have emerged online, bringing practitioners together from around the world. Many who attend have reported it is the first time they have not had to leave race out of the dharma hall, the first time that they can bring all of themselves to a gathering without fear of being told they are sabotaging the meeting or that their issues have nothing to do with Buddhism, mindfulness, or recovery.

The answer to the second question—sustainability—is perhaps not so straightforward. Sanghas are difficult to build and maintain, even in the best of circumstances. Seiho Morris, a Rinzai Zen priest, points out that “it’s an interesting thought to have Black-only sanghas, but in the Zen world there are very few BIPOC teachers. I know it is different in the Vipassana world, but still, the most basic question is, are the numbers there in terms of people to support and maintain a Black-only sangha? Because it requires a lot of energy, time, and recalibration.”

The key to sustaining Black-only sanghas is found in Mpyisi’s last question: why? What is the rationale—from within the dharma—for gathering together but alone?

In the Black churches of the US, the UK, and Canada, one often hears sermons encouraging people to vote or teaching how to work with microaggressions. Yet in dharma halls, we are still told there cannot be statements like ‘Black Lives Matter’ on the center’s website because it is ‘too political.’

In white-centered Buddhist spaces, we often hear the refrain that the Buddha’s driving motivation was to find enlightenment. This is a misinterpretation. What Siddhartha actually vowed to do was to not move from his spot until he found an end to suffering. Emphasizing enlightenment while de-emphasizing real-life suffering not only negates the Black experience but also creates an opportunity for spiritual bypass by white teachers and students. Siddhartha, in his compassionate resolve, modeled for us the way to find an end of suffering for all, by coming face-to-face with Mara: our mental states, our past lives, and all our personal suffering.

We as Black people, in every moment, confront our own Mara. Everything is a reminder of the suffering we have inherited. Even as the pandemic disproportionately affected those of Black and African descent, it also opened up opportunities to meet and practice together in safety. No longer did we have to worry about traveling to a dharma hall for a teaching and wondering if we will be stopped by the police on our way home. To leave our homes is to fear being killed by the police or by a white supremacist—every time. Every time a police car passes, my heart races, and I stop to let it go by.

The twelfth-century Zen teacher Dogen wrote, “To study the Buddha way, we must study the self.” As Black people, that means understanding how we got here and what that still means for us today; as Buddhists, it means knowing what Black Buddhism is and having the freedom to discover it. Arisika Razak, a teacher at East Bay Meditation Center and cofounder of African Healing and Wisdom, says, “Since the Maafa [African Holocaust], there is a continuity of culture, which is about resistance and joy, yet we are still openly hunted down in the streets. We need to take this practice into our culture. We need to make it ours. We survived the slave ships by moaning together. We need to integrate the body, our songs, our drumming.” In other words, we have to study the legacy and burden of slavery before we can, as Dogen said, be “illuminated by the myriad things.”

Razak believes we can learn a lot from Black churches in America. “When African Americans were given Catholicism and Protestantism, those communities tried to reinforce the notion of inferiority, of slave and master. However, over time, we created a place that both soothed our souls and created a pathway to liberation.” Buddhism, which has a long history of integrating the teachings with whatever culture it encounters, can and will become a space for the same thing.

Rehena Harilall, the founder of UK-based Buddhists Across Traditions, says, “This space offers the unique ability for us Black-identified people to process and heal the relationships between Black folk, a space where we can process the pain and suffering unique to Black folk.” Part of that pain is the legacy of eugenics and the deep cultural belief that Black Africans were savages who could not be tamed, that they were not even fully human. We still feel that. In the aftermath of the public lynching of George Floyd, I needed to be in a Black-only space; I did not want to be around white people as I grieved. Especially in those moments, being in an all-Black sangha matters. It enables us to liberate ourselves from the social construct that being Black is an aberration from normal.

Within Black sanghas, we find the seeds of a Black Buddhism. It’s a Buddhism committed to seeing the truth of who we are—not just our shared buddhanature, but also our shared humanity—without pretending that our experiences of this human life are the same. It returns us to the four noble truths with an understanding of suffering that goes beyond the personal and recognizes collective and historical pain—and fear. It is born of a deep knowledge of interdependence, not only of how the myriad things inform what we face today but also how we must, if we are to transform the world, face it together.

Thich Nhat Hanh has taught for years that “it is probable that the next buddha will not take the form of an individual. The next buddha may take the form of a community, a community practicing understanding and loving-kindness, a community practicing mindful living.” The future buddha, in other words, will be a sangha. And when it arrives, when it takes shape, that sangha—that buddha—will have more than one face.

In the Triratna community, the “Threefold Puja” reminds us that “As, one by one, we make our own commitment, an ever-widening circle grows.” It’s happening now. There has been a call to action—the Buddhist world has expanded to have Black sanghas alongside Asian sanghas, Latinx sanghas, and white sanghas. “During this pandemic, by the great miracle of technology, we as people of African descent have found each other,” says Moka Case, a facilitator of Afrikan Healing and Wisdom, a Black-only group run out of Insight LA. “The dominant culture can no longer keep us apart.”