Zoketsu Norman Fischer’s commentary on Mumonkan Case 14: Nanchuan’s Cat.

The Case

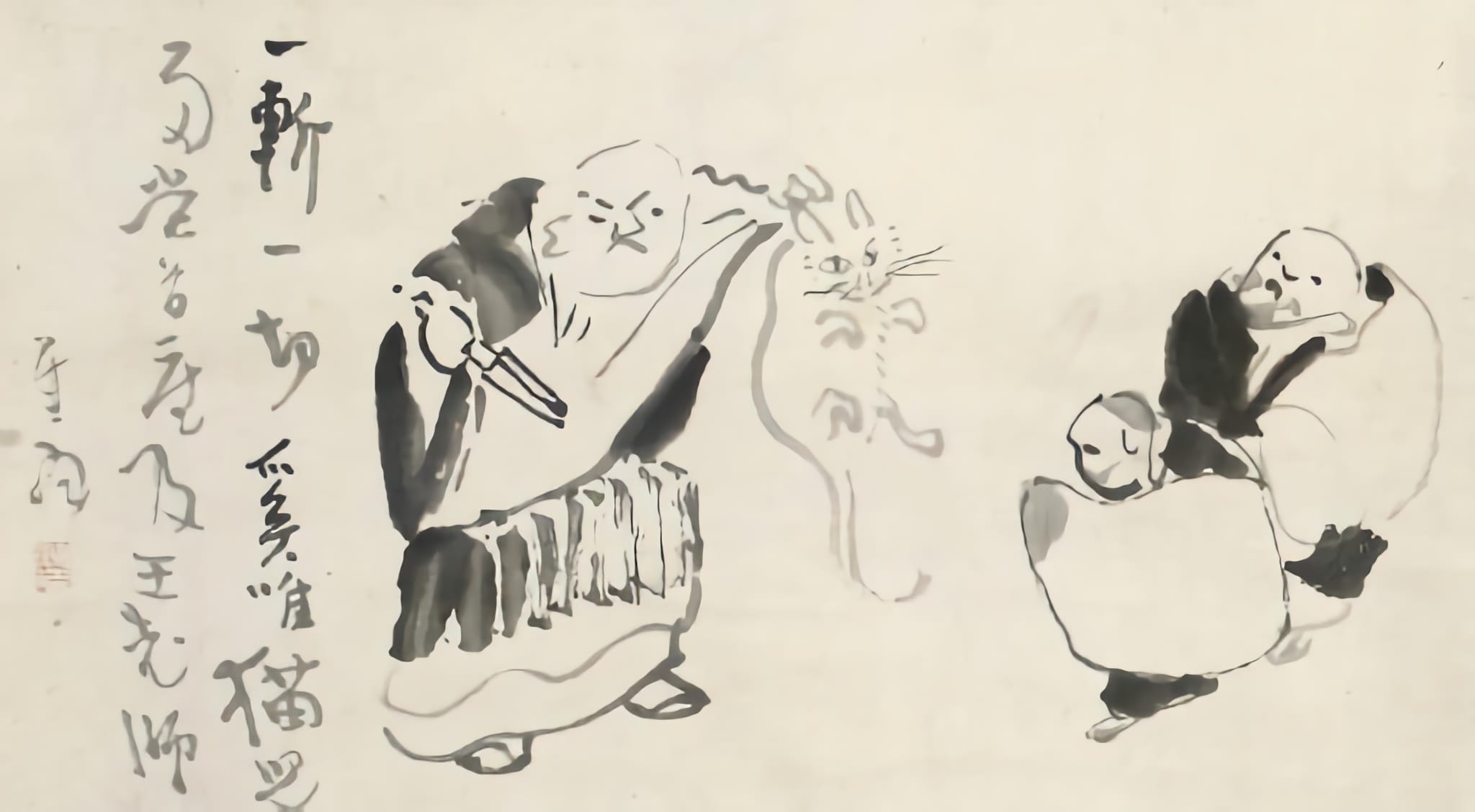

Nanchuan saw the monks of the eastern and western halls fighting over a cat. Seizing the cat, he told the monks: “If any of you can say a word of Zen, you will save the cat.” No one answered. Nanchuan cut the cat in two. That evening Zhaozho returned to the monastery and Nanchuan told him what had happened. Zhaozho removed his sandals, placed them on his head, and walked out. Nanchuan said: “If you had been there, you would have saved the cat.”

Mumon’s Comment

Why did Zhaozho put his sandals on his head? If you can answer this question, you will understand exactly that Nanchuan’s action was not in vain. If not, danger!

Mumon’s Poem

Had Zhaozho been there

He would have taken charge.

Zhaozho snatches the sword

And Nanchuan begs for his life.

This story involves Nanchuan (Japanese: Nansen) and Zhaozho (Joshu), two of the most important figures in Zen history. Zhaozho came to Nanchuan when he was only about twenty years old. Nanchuan was lying down taking a nap when the young man approached. Sitting up in bed, he asked the Zen question (a wonderful question for anyone at any time), “Where have you come from?” Zhaozho replied, “I come from Standing Buddha Temple.” “Are there any standing Buddhas there?” asked Nanchuan. Zhaozho replied, “Here I see a reclining Buddha.” Zhaozho was a sincere, steady practitioner, devoted to his teacher, with whom he remained for forty years. They were very close, as this story shows, and they worked together to create a good learning environment for the monks.

Both Nanchuan and Zhaozho figure in many stories in the koan collections. The present case is probably the best-known—and most disturbing—case in all of Zen. We could compare it to a similar story that appears in the Bible, involving the wise king Solomon and a baby. As the tale goes, two women are arguing over a baby, both claiming to be the mother. Like Nanchuan, Solomon proposes to solve the dispute by cutting the baby in two. He intends to give half to each of the women, an eminently fair solution. One of the women speaks up immediately and says, “No, don’t do it. I am not the mother. Give the child to her!” And so Solomon discovers that she is the real mother, the one who cares most for the child’s welfare.

The Solomon story is tidier and nicer than the story of Nanchuan and the cat. We can easily discern its point, whereas Zen stories seem harder to appreciate. People get confused when you say to them, “Say a word of Zen!” They can’t help but think there is something to this that they don’t understand. It paralyzes them. They can’t say anything. They think about it in a panic, and the more they think the more baffled they become. A Zen monk is not half as smart as a mother. A mother knows about love and devotion, so she is never speechless when it comes to the welfare of her child. If the mother in the Solomon story had been there she would have said to Nanchuan, “What’s the matter with you? How can you even think of killing that cat? You are a Zen priest who has taken a precept against killing!” Surely these words would have saved the cat. If the monks had been reasonable ordinary feeling human beings instead of stupid monks with Zen gold dust in their eyes, they would have spoken up like that or simply grabbed the cat and run away. But they couldn’t do it. Maybe they were too intimidated by the prestige of the teacher.

In commenting on the case, Dogen said, “If I were Nanchuan, I would have said, ‘If you cannot say a true word of Zen I will cut the cat, and if you can say a true word of Zen I will also cut the cat.’” This would have been a much less misleading challenge than the one posed by Nanchuan. If I were one of the monks I would have said, “We can’t answer. Please, Master, cut the cat in two if you can.” Or, “Nanchuan, you know how to cut the cat in two, but can you show us how to cut the cat in one?” And again Dogen says, “If I were Nanchuan and the monks could not answer, I would say, ‘Too bad you cannot answer,’ and then I would release the cat.”

We are all cut in two of course. That’s living in this world of discrimination and difference. I am me; therefore, I am not you. But we are also cut in one, only we don’t know it. Being cut in one is “I am me and all is included in that, you and everything else.” We practice zazen to remember that we are cut in one, as well as two. When we are dead, we’ll all be cut in one and only one. But we are dying all the time. If we are Zen monks, we devote ourselves to sitting on our cushions so that we can see this and integrate it into our everyday living. When Zhaozho comes back later and puts his sandals on his head, this is what he is saying. Putting a sandal on the head was a sign of mourning in ancient China. Zhaozho is expressing, “Teacher, do not fool me with your pantomime. You and I both know that the cat is already dead. You and I are already dead. All disputes are already settled. All things are beyond coming and going, vast and wide, at peace.”

This same story appears in the two other major koan collections, the Blue Cliff Record and the Book of Serenity, and the commentaries there say that Nanchuan did not cut the cat in two but only pantomimed doing it. Zen teachers do not commit murder, the commentaries say, even to make an important point.

In Zen precepts study it is always noted that there are three levels of precept practice—the literal, the compassionate and the ultimate. On the literal level we follow the precepts according to their explicit meanings—not to kill means not to kill, not even a bug. But on the compassion level we recognize the complexity of living—sometimes not to kill one thing is to kill something else. The network of causality is endlessly complex; our human ideas cannot encompass it. We recognize that precepts will be broken sometimes and we affirm that our guide for precept practice will not be literality but compassion. We will follow precepts with a heart of love for beings. That motivation may sometimes cause us to break precepts in order to help someone.

On the third level of precept study, the ultimate level, we recognize that there is no breaking precepts. Precepts can neither be broken nor kept, for they—like all that is—are empty of any identifiable self. When we understand this deep truth, we naturally want to follow precepts with a wide and flexible heart. This case involves the ultimate level of precept practice: the recognition that there is no killing, that life can never be killed—or to put it another way, that life is already dead. When we know life at this level, we can really appreciate its preciousness. It is this recognition that Nanchuan and Zhaozho have, but that the monks lack.

This is not just Zen talk. It’s really true. We think death is later, but death is not later. It’s now, as each moment passes irrevocably. No wonder we can’t see this. It’s too terrifying! Our death doesn’t happen all of a sudden; it happens gradually—and always. But it is also true that our death never comes. When we enter what is conventionally called “death,” the “I” we have always thought we were melts away, but the “I” we always actually were and always will be remains, as ever, unmoving. Although this may sound paradoxical, it’s a plain truth, probably the most basic of all human truths: we are always dying, and there is no such thing as death. Seen in this light, the precepts are ultimately not simply rules of ethical conduct, a list of do’s and don’t’s. They are possibilities for us to understand life’s profundity through our conduct in the ordinary world. Practice of the precepts takes us to the root of what it means to be alive, to the center of the human problem of meaning. We are always faced with the question whose depths we will never be able to fathom: what do I do with this life now? This is precepts practice.

We should back up a little bit, though: the monks in the east and west hall were arguing about a cat. In most monasteries in ancient China the community was divided. Some monks lived in the meditation hall, devoting full time to formal practice, while others were working monks who did the necessary support work for the monastery: cooking, farming, fixing, chopping firewood, and so on. These two kinds of monks were probably housed in different halls, the east hall and the west hall.

As soon as there are two halls and two functions, there are different viewpoints and inevitably there are disputes over which viewpoint is correct. In our Zen Center exactly this thing used to happen all the time. It probably still does. The monks who specialize in work think the monks who meditate a lot are indulging their taste for peace and quiet and are unrealistic about the world; meanwhile, the meditators think the workers are too worldly and are not really interested in doing the practice. This clash of perspectives happens in all monasteries and there is sometimes great strife. The Catholics had conflicts between the choir monks and the lay brothers that went on for centuries until Vatican II, a sweeping program of reform instituted in the 1960’s, abolished the tradition of lay brothers.

The same thing happens of course, and much more tragically, in the world at large. Jews—to take one drastic example among many—think Israel is their place, and that their customs and traditions should prevail there, while Palestinians think it is their place, and therefore their customs and traditions should prevail. Neither side considers its view to be merely a preference, an option among options. It is the truth. In Nanchuan’s monastery maybe the working monks thought the cat would do very well in the kitchen as a mouser. The meditating monks, whose minds were very subtle, tender and compassionate, could not bear the thought of a cat killing mice. This was, after all, murder! So the monks fought over the cat. When there is difference and the underlying essence of difference—which is oneness—is not understood and appreciated, there will always be fighting. None of us is free from being blinded by our own view. So how do you handle this kind of situation? Which side are you on? What do you do? Nanchuan demonstrates.

In Zen a knife always suggests Manjushri’s sword of wisdom that slices through emptiness, cuts through duality. It sees that life and death are intertwined, good and bad are intertwined, Israelis and Palestinians depend on each other. Manjushri’s sword cuts through attachment to view, showing that all views depend on each other and arise from an underlying unity that is no view. The truth is beyond views; it is just life as is really is—unexplainable.

So Nanchuan uses Manjushri’s sword in a little piece of street theater designed to take the monks’ dispute to another level. Never mind the cat, he is saying—what is life, what is death, why are we alive? You monks—and all we humans—are arguing over a cat while the world is burning up in front of our eyes! Wake up! Don’t waste time! The problems of the world are actually fairly easy to solve. But people can’t get along, can’t work together, can’t harmonize their views, so nothing gets done. Things only get worse. Technical and social solutions are at hand, but political problems block them at every turn—and that’s the worst problem in the world.

I think this case strikes to the heart of what it means to be a monk in the world, which is our challenge as dharma students: to be fully committed to our practice, to make it the only thing in our lives, and yet to honor our daily activity in the world as the expression of our practice. How do we do that? We are all monks of the east hall—and of the west hall. We are all activists and quietists. How do we manage this?

Thomas Merton wrote about the special function of the monk for the world. The monk, he felt, lives life radically in holiness, apart from the world. Monks are unusual people. They are and must be outsiders. This means they are not on any one side. They are committed to truth, which means love, so they can’t be attached to one side or another. Monks can’t hate. They can’t justify their views as right. They must always come back to the center, to zero, to the present moment, the in-between moment, beyond views.

So although monks may live harmoniously in the midst of society, they are always subversives—working internally and externally against the dominant modes of greed, hate and delusion that make the world go round. Monks are living examples of an alternative to the self-centered ways of the world. They are secret agents of a foreign power—the power of selfless love. Not that they have a superior attitude about this. In fact the most important practice for a monk is humility, which is the practice of being aware of the selfishness that arises in our own mind continually, while remaining clearly committed to the effort to go beyond selfishness—and to encourage others to do the same.

I know a Christian hermit whose lifetime has been devoted to the study of the writings of Simone Weil. Weil was an extraordinary person, a French Jew who was a Catholic mystic. Her life was a testament to this union of the opposites of activism and quietism. She was a mystic through and through, and yet most of her life was spent in extreme political activism. She was a witness for peace in the Spanish Civil War, a Marxist who wrote for a workers’ newspaper and was active in workers’ parties. She worked in an automobile plant and as a grape picker so that she could be in solidarity with ordinary working people. Living in England during World War II, sick from overwork, she died of starvation because she refused to eat any more than the French resistance fighters, who were living underground at the time. Weil thought of her activism in mystical terms. She spoke not of justice or power but of attention, which she defined as “a point of eternity in the soul.” If we can pay attention closely enough, she thought, we will come to know the transcendent, for it lies at the center of the human heart and mind.

In terms of our story, if you practice paying attention thoroughly enough you will see that cutting the cat in two is cutting the cat in one—that because we are all different, we are all already one. So, passionate as your views may be, you do not want to take sides and engage in bitter disputes. Instead, you want to appreciate and understand and weep with the suffering of the world. You want to intervene in disputes, grabbing hold of the cat and saying to everyone, “Wake up, take a look. Let’s take a look together. Let’s go beyond our differences and see what we are really all about as human beings.” How to do this in the midst of a particular situation is not always obvious. Maybe it takes a great master like Nanchuan to have the nerve to do it. But maybe not. Maybe we all have to learn to have that much nerve, getting up from the meditation cushion to become involved in our world of twoness and manyness, with the monk’s spirit of oneness.