Josh Korda on what his irritating meditation partner taught him about being with aversion and overcoming anger.

A little over a decade ago I spent my first retreat with a wonderful British Theravada monk—Ajahn Sucitto—and found myself arriving to the meditation center with an aspiration that the time would provide relief from the frustration and distress I was experiencing during my working hours. This was quite understandable as, at the time, I was freelancing at an advertising agency as an art director, an endeavor that could drive even the sturdiest souls to despair. I was hoping for a few days of freedom from the “What the hell have I done with my life?” rounds of internal condemnation.

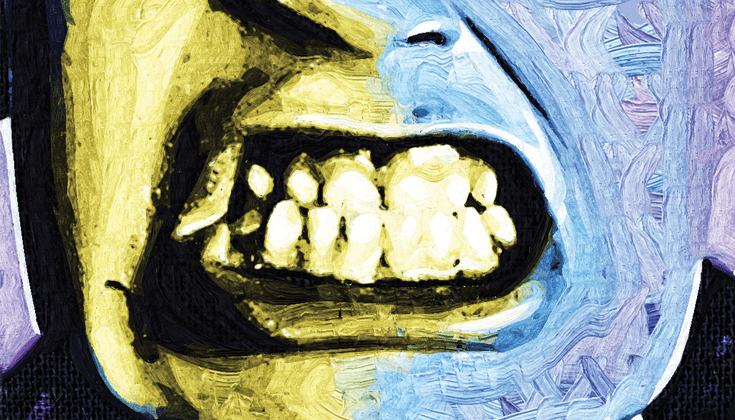

Within the first few hours of the morning sit, walk, sit routine, I had found myself seated next to what seemed, over the course of the first day, to be the single most irritating human being on the North American continent. Here was someone capable of breathing in loud, snorting inhalations and wheezing exhalations. Huffing was involved as well. As if this was not enough to crack my fragile spirit at the time, the fellow also seemed incapable of remaining in a single posture for more than five minutes, before shifting—audibly—into a new position, in movements that required far more time and effort than really necessary. His very existence was an affront on the senses; I even found his clothes to be off putting. It seemed, in short, as if he was consciously trying to ruin my retreat!

Now, many of us have heard about, read about, or seen, on TV’s Portlandia, the phenomenon of the “Meditation Crush.” I was in quite another state of affairs. Let’s call it The Meditation Malice.

Instead of fantasizing about a life spent with a complete stranger, I spent a lengthy period of those sits imagining the various ways I would tell off another practitioner during the lunch break—even though that would require breaking noble silence—complete with a self-righteous speech about the point of silence in the spiritual life. (It somehow didn’t occur to my mind that far more noise was resulting from this inner chatter than the actual shuffling nearby.)

Of course, the virtuous and spiritual components of my mind were appalled by my lack of compassion, tolerance and forgiveness. I tried in every manner possible to relieve the aversion, by focusing on relaxing my belly and unclenching my jaw, lengthening and refining my out breaths, Metta, forgiveness phrases, reciting the dhamma and so forth. I was, after all, not a novice, but someone who’d been practicing for many years by this time. Yet the situation grew worse, as if every movement the guy made was amplified. Worse, when the time came to listen to the monk, the fellow spent much of the time stealing glances at a cell phone, and then had the audacity to raise his hand during the Q&A section. His question was predictably insipid.

It was only during the second day of the retreat when I heard Sucitto mentioning something about “being with aversion.” (I wish I could remember exactly what he said, but I was too busy hating on the fellow sitting next to me to take in much of the talk.) It was in that instant that I realized how the spiritual work wasn’t being ruined by this interloper, but rather all the shuffling and huffing, and my reactive antipathy was providing me with an entire raison d’être for the retreat: to learn how to work with whatever is present — distractions and resentment — rather than clinging to my expectations. After all, I had arrived in full-blown aversion to my work; what else did I need to explore, but relating to the experience of ill will?

It was then that I saw clearly that I was turning to my practice as a form of spiritual bypass; trying to get meditation to relieve me of aversion, rather than creating a safe container that could hold human emotion without becoming shaken and stirred by its distracting sideshow, divisive thoughts.

It was a very valuable lesson: The content, in and of itself, of life is far less important than how we relate to our experience; anger is just another visitor to the ongoing party in the mind; its only when we try to “get rid of” a visitor that the drama really begins. Resistance is suffering, as they say. In the bouncing back and forth between dislike and embarrassment over having enmity during a retreat, I had left no room for emotions to express themselves in the body, where they could arise and pass without being attached to or repressed. And so the work became simply noting when the annoyance appeared, allowing it to express itself somatically, while keeping my awareness spacious enough that other sensations — background sounds, contact sensations with the cushion and clothing, etc — could be perceived as well. As the Buddha taught, if the mind is as vast as a large body of water, a spoonful of salt can’t ruin its taste; it’s only when the mind contracts to the size of a small cup that the salt makes it undrinkable.

Eventually, as I focused less on the fellow seated next to me and more on the feelings beneath the experience, I found that my aversion was really much older, a presence that had longed for attention for many years, but had been numbed at times by suppression, distractions or alcohol. Finally I had the opportunity to attend to this entirely human energy; and that is what we all seek, after all: a safe, tolerant space where no authentic attribute is rejected, shamed or, conversely, indulged.