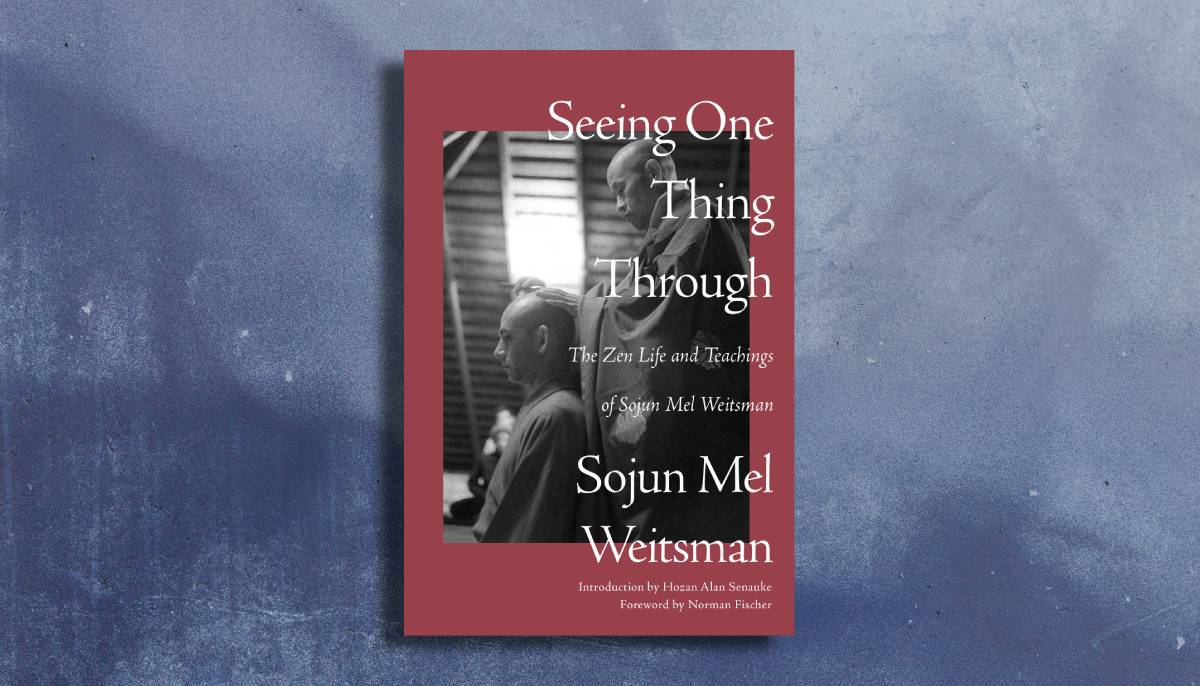

This excerpt from Seeing One Thing Through: The Zen Life and Teachings of Sojun Mel Weitsman, by Sojun Mel Weitsman is provided courtesy of the publisher, Counterpoint Press. We thank Counterpoint for sharing this with Buddhadharma’s readers, and we thank our readers for supporting dharma publishers.

Practice-Enlightenment

Our Zen practice is very simple. And yet the focus is easy to miss. As a matter of fact, it’s so simple that sometimes we don’t see what’s right under our feet, or in front of our nose. To be able to take hold of and seize this moment and not get lost in the world, not to give way to confusion and doubt, is pretty difficult, and yet this simple practice is not so difficult if we always question, “Where am I and what am I doing?”

This “What is it?” is a koan for each one of us. I have always felt that this “What is it?” was Suzuki Roshi’s unstated koan for us. I could sometimes hear him saying this in a casual way, but loaded with meaning. If someone pointed something out to him, he might say, “What is it?” After all, what is this bow? How do we become aware of the absolute quality of our life in each moment’s activity? It’s maybe not so difficult to be aware of what we’re doing, but to be aware of the absolute quality of our life in each activity is easy to miss. How to express Buddha-nature in the simplest acts of our life. How to express our whole being, which is not just our personality. Whenever someone asked Master Gutei a question, he raised one finger. When he raised one finger, he was saying, “This is it!” This is it! Everything in the whole universe belongs to this one finger, and this finger belongs to the whole universe, the Dharmadhatu. The whole universe is supporting this finger.

When we say that we are doing something such as walking or eating, what does that really mean? What is that? In one sense, there’s “Hey, leave me alone and let me enjoy my meal,” but in another sense, the universe is eating potatoes with a knife and fork. It is a little word, but it has a big meaning. It has no special name or object, but we can point to anything and say “This is it.” If I point to you, I can say you are it—depending on the situation. Yet each it, John or Mary, the table or the chair, has its respective name. And at the same time, each one of them is it. So if we say “What is it,” it has no special name, no special form, no special characteristic, but every name, every form, every color is It. What is it? What is it? What is it? As Ganto says, the answer is always: “This is it.”

If we can keep our attention on This is it, then we have our practice. It’s not that we know something, but we express right understanding. I may know what something is, yet not know that this is it. Even though I don’t understand it, I know it. The barbarian knows it, even though he doesn’t understand it.

Question: You say that after enlightenment, begins hard practice. So if this is it, what’s going on before?

Sojun: We think that delusion precedes enlightenment. We tend to think in terms of before and after. Delusion is first, and we work hard to get something called enlightened. It does look like that, but enlightenment is our nature, our true nature that is always with us. When we say “get enlightened,” it’s not that we actually get something. It means to bring forth light, to let go, so that light can shine forth. Enlightenment is an expression of our true nature, but that doesn’t mean that we necessarily realize it.

So what’s before realization? There is obscurity, confusion, dualistic thinking, yours and mine, right and wrong, good and bad. After enlightenment, there’s confusion, right and wrong, good and bad, but it’s not the same. We sometimes think that enlightenment means the reconciliation of all dualities. You and I may be angry with each other before enlightenment, and when we become enlightened we reconcile anger with serenity. After enlightenment we may still get angry, but that anger is not the same. You are not attached to that feeling.

Enlightenment is the beginning of our practice. Enlightenment is what motivates us toward practice. The fact that you want to practice means that the enlightenment that is always with you needs to somehow be expressed. It is usual to think that we enter practice in order to get enlightened, but enlightenment is actually driving our practice. We have a tendency to see it the other way around. “If I work real hard, I can get enlightened!” That’s good, but it’s enlightenment that’s motivating you to work real hard to seek enlightenment. What we are all looking for is what we already have in abundance, but we don’t know that until we wake up to it. And then we might say, “Now that I’ve awakened to it, I don’t have to do this troublesome practice any more.” But if it’s actually enlightenment that you have awakened to, you won’t want to stop, because enlightenment is within our effort, within our practice. Practice brings forth enlightenment, and enlightenment creates practice. Practice is the basis and enlightenment is its expression and extends everywhere. It’s not confined to a certain place or activity. This is it. Now please pass the salt.

Stand Up in the Middle of Your Life

There is this question: What is our practice? What are we doing? Is it vital enough? Are we sinking into complacency? Do we have enough pressure to feel that we’re doing something vital?

It’s important to have pressure. Some people feel the pressure more than others. One person may feel that pressure is a burden and another may feel that it’s okay, or that it’s not enough. Each one of us is in a different place in our practice, in our dispositions, in our character, in our strength, and in our ability, in particular in our ability to accept things as they are and to have equanimity and concentration. We’re all different. Even though we have the same practice, there is something about the practice, the fine-tuning of our practice, that has to be tailored to each person.

What is it that we can all practice that is vital for each one of us? What is the koan that covers everyone? There are a couple of koans that I sometimes give people, and there are a couple of practices that I sometimes give people. If someone has a very angry disposition and suffers a lot from self-alienation, I may give that person a Metta practice, either reciting the Metta Sutta or practicing the four aspects of Metta. The first aspect of Metta is to bestow love or acceptance or light on yourself, the second is to focus love on someone you know. The third is to focus on someone you don’t know, and the last is to focus on someone you consider an enemy, and then extending that love to the whole world, to the whole universe. In any case, all of this begins with knowing yourself and accepting yourself. I introduced the Metta Sutta into our service at Green Gulch because I felt it was something we really needed to think about as a balance to our wisdom practice.

Dogen Zenji gave us the Genjokoan, the koan of our daily life—how we meet every aspect of our life as the koan; the fundamental point where sameness and difference meet. We have collections of one hundred koans, fifty koans, and so forth, and those koans are examples from the daily lives of the ancestors. In the same way, our true koan appears within the intimacy of what is actually happening in our life. So when we study the old examples, they are not just stories about someone else. Because these stories are so fundamental, we can relate to them as our own.

“What is Metta?” is a koan. It’s a wonderful koan. “What is gratitude?” is a koan. I often give people the koan of gratitude. No matter what happens to you, just bow and say “Thank you,” whether you feel it’s a good thing or a bad thing. If someone insults you, just bow with gratitude and say “Thank you.” If someone compliments you, just bow with gratitude and say “Thank you.”

Sometimes it’s hard to accept a compliment. Someone may say, “Oh, you’re nice, or you did this well.” It can be very hard for us to accept that. What are we supposed to say? Anything we say makes us feel either egotistical or evasive. Every time I take my dog for a walk, someone will say, “What a beautiful dog you have!” The dog doesn’t care, and it’s no compliment to me, but I feel obliged to come up with something. So sometimes I say thank you and sometimes I just agree. How do you accept a compliment without being egotistical? As someone said, “How do we cut through?” Right there is our practice. It’s not thinking it over, it’s “How do we cut through?” If we’re dealing with this kind of koan all the time, we don’t have any problem about whether there is pressure or not enough pressure, or whether we’re at the edge or not at the edge. If you can accept this koan that is always right in front of you, you will be right at the edge all the time. The only problem is the problem of ego. We don’t have to know so much. We don’t have to be so smart. We just have to be able to stand up in the middle of our life and accept whatever it is.

Excerpted from Seeing One Thing Through by Sojun Mel Weitsman, reprinted with permission from Counterpoint Press

For a review of this book, see the Fall 2023 edition of Buddhadharma on Books.