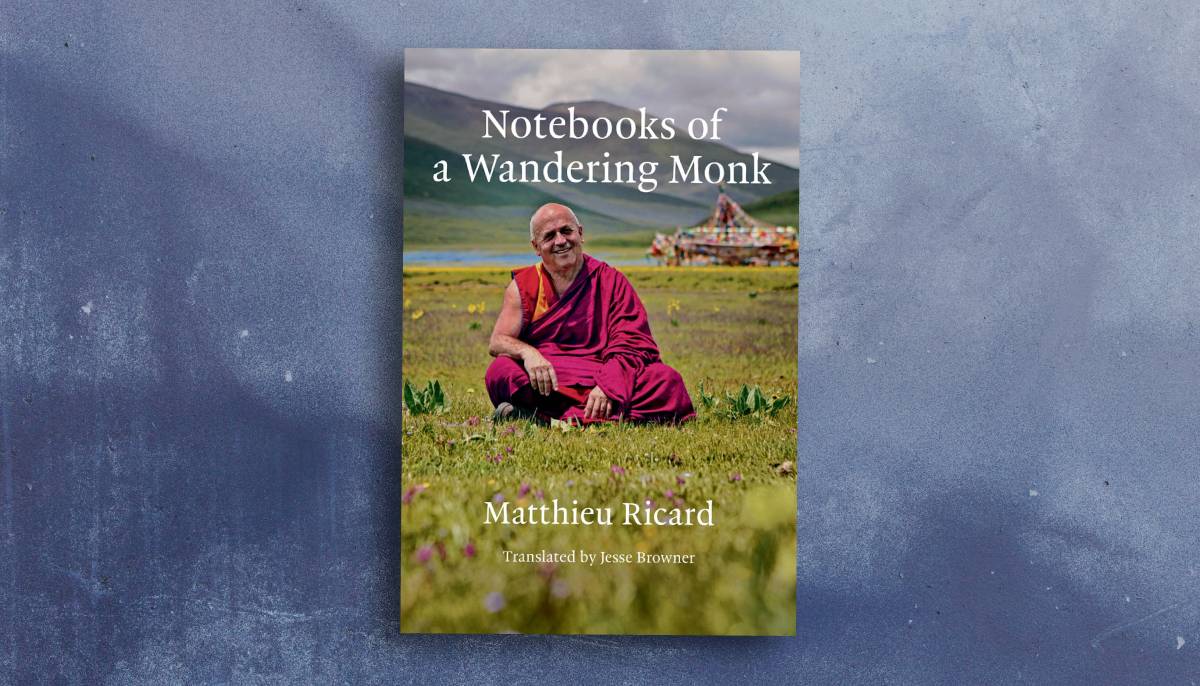

This excerpt from Notebooks of a Wandering Monk by Matthieu Ricard.— as reviewed in the Winter 2023 issue of Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Guide — is provided courtesy of the publisher, MIT Press. We thank MIT Press for sharing this with Buddhadharma’s readers, and we thank our readers for supporting dharma publishers.

A Teacher’s Return to The Valley of Renewal

A visit from Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, the incarnation of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s second spiritual teacher. A great celebration is held and blessings apportioned at Dzongsar, his home monastery. Portrait of Lodrö Phuntsok, the man who rebuilt the monastery and revived the valley’s traditional arts and crafts.

“The lama’s coming home!” The long-awaited news spread like wildfire and thousands of peasants and nomads hastened to greet Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche. Some came from the neighboring valleys, others down from the mountain meadows where they pasture their yak herds at 15,000 feet in the summer months, leaving a few family members behind to tend to the animals. The herders would return to the highlands the next day so that their loved ones could come down in turn and receive the lama’s blessing. His 2004 return was an event; it was only the second time, sixteen years after his 1988 visit with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, that Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche had returned to his predecessor’s monastery from India.

Hundreds of tents were set up along the riverbank on a vast plain facing the Dzongsar monastery, located south of Derge, the capital of Kham, eastern Tibet. These tents are woven from thick white cotton and decorated with arabesques made from blue or black strips of fabric that are cut out and sewn by hand. The largest, veritable big tops, can hold several hundred people. One was of particular interest to the crowd. It was there that the lama would be staying in the days to come.

Some horsemen who had gone off to greet the master came galloping back: “They’re coming! They’ve already passed the Mechö bridge!” Everyone got busy. Some monks got out their fifteen-foot telescoping trumpets while others adjusted the mouthpiece of their gyaling, a kind of oboe made of red sandalwood inlaid with gold and silver. The welcoming procession took up its place in joyous chaos. I scrambled up a promontory to photograph the scene from a good vintage point.

A hundred horsemen sitting proudly on their steeds appeared in ceremonial regalia – billowing white trousers of wild silk, coats of brown wool and scarlet turbans. They brandished standards and banners that rippled in the wind as they galloped towards the tents, cleaving the swells of aromatic white smoke rising from multiple pyres of juniper lit by the faithful. Before the laughing crowd, some horses bucked while others balked – but it takes more than that to unseat a Kham horseman!

“Here he is!” A couple of miles from the encampment, the lama had ditched the all-terrain vehicle he had been riding in for the past three days from Chengdu, swapping it for a brown horse caparisoned in brocade and silk scarves. The animal’s mane and tail had been braided with brightly colored ribbons.

The people of the region hold Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche in such deep devotion because the lama, who was forty-four years old at the time, is the reincarnation of one of the most revered masters of old Tibet, Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, who lived at Dzongsar; he was one of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s primary teachers, and died in Sikkim in 1959, a year after fleeing the Chinese invasion. In 1988, Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, who was born in Bhutan, had accompanied Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche on his second trip to eastern Tibet and visited his predecessor’s monastery for the first time.

The people, lined up on both sides of the road, bowed respectfully when the lama passed by, and threw armfuls of flowers in welcome. During the three days of festivities held in his honor, they literally gorged themselves on his presence. The lama, in the middle of the procession led by musicians, was escorted by horsemen who opened a path through the ocean of humanity. He finally reached his tent, where he rested for a few minutes before emerging to meet with all those who had come to pay him tribute and give his blessing to the hordes of the faithful.

By this time, there were several thousand nomads sitting in the meadow before the great tent. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche took his place on a chair and, using a battery-powered microphone provided by the monastery, offered his best wishes to the assembled crowd. He then related the circumstances of his coming, gave a few teachings and some basic life lessons, urging each and every one to avoid quarrels at all costs, as they are quite frequent among those rugged nomads. He asked if anyone was ready to commit to giving up alcohol, for which half of the members of the audience raised their hands as a pledge; to stop smoking, for which almost all raised their hands; to quit hunting, protect the environment and stop littering nature with plastic bags – here too, a majority promised to abide. This exchange was made in a good-natured, humorous mood. As for the crowd, they laughed wholeheartedly to see who had promised and who had not.

It was now time for the benediction. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche recited a sacred text and performed the long-life ritual. He then stood and walked slowly among the people, touching the head of each one with a blessed statue. He was led by a hieratic monk who opened a way through the crowd by waving a stick of incense and a white silk ceremonial scarf to the right and to the left. Paths seemed to open of their own accord through the crowd, and two or three rows of kneeling followers at a time received their blessings. Men, women, children, and the elderly sometimes collapsed onto one another. Their eyes gleamed with joy and reverence. Some recited prayers out loud, wishing happiness to all beings and a long life to the lama.

Throughout the two hours that the blessing ceremony lasted, two monks continuously played the gyaling, a traditional instrument somewhere between a flute and trumpet, often richly ornamented. A listener who is unfamiliar with these woodwinds may be astonished at the ability of the monks to draw a continuous tone from them for minutes on end. In fact, the players use a special technique known as “circular breathing,” which allows them to blow into the instrument without interruption by gradually expelling a pocket of air created by puffing out their cheeks while they fill their lungs through their nostrils.

We spent most of the day with him in the tent. Our group included Raphaële, two monks from Shechen, and three English volunteer physicians working with Karuna-Shechen, who were astonished by the sophisticated understanding of Western culture apparent in Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s conversation.

The heir of a long line of great spiritual teachers and a refined connoisseur of Buddhist philosophy and the schools of Western thought. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche has lived and taught on five continents and is as comfortable on the high plateaus of Tibet, in Hong Kong, or in London as he is in the old neighborhoods of Delhi. He is the director of several centers and monasteries and of philosophical college, and has written several books, including What Makes You Not a Buddhist1 and Not for Happiness.2 Under the name Khyentse Norbu, he has made several films, including The Cup, which was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. He is the initiator of several major projects, including the Khyentse Foundation and Siddhartha’s Intent, which work to preserve the spiritual and academic heritage of Buddhism, and the 84000 initiative (84000 being the number of aspects of the Buddha’s teachings), whose mission is to translate from the Tibetan, by 2035, the entirety of the Kangyur, the collection of the Buddha’s words (103 volumes), and that of the Tengyur, the commentaries of his Indian disciples (213 volumes) by 2110 (see www .84000.co).

The afternoon was winding down. The lama now headed to the monastery, where he would spend the night. Again, a long procession formed to accompany him the mile and a half from the temporary encampment to the hill on which stood the monastery, which had been restored over the course of the past fifteen years. Shortly before arriving, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche dismounted from his horse and walked the last 100 yards, in a sign of respect for this sacred place and all the great teachers who have lived there. Then, still preceded by musicians and monks waving banners, he took the narrow alleyways that led to his residence. There too, a dozen visitors waited to meet with him in private, share news with him or ask his advice. It was the same early the next morning, before Dzongsar returned to the festivities taking place over the next two days: equestrian games, folk dancing and, yet again, the blessing of the crowd.

Excerpted from Notebooks of a Wandering Monk by Matthieu Ricard. Translated by Jesse Browner. Published by MIT Press.

For more on the latest dharma books, read this issue’s edition of Buddhadharma on Books. Or see more excerpts and other digital exclusives for Buddhadharma readers here.