It’s not as if times of fear and despair are anything new. People have fought wars, struggled to survive, faced injustice, experienced loss, dealt with violence and greed, and been caught up in historical movements beyond their control pretty much forever.

Life has never been that easy.

In Buddhist practice, you learn never to shy away from facing the pain of the human condition. At the same time, you also learn not to shy away from the beauty and value of life in all its forms.

By clearly seeing the extremes of experience, you learn to scout a middle way.

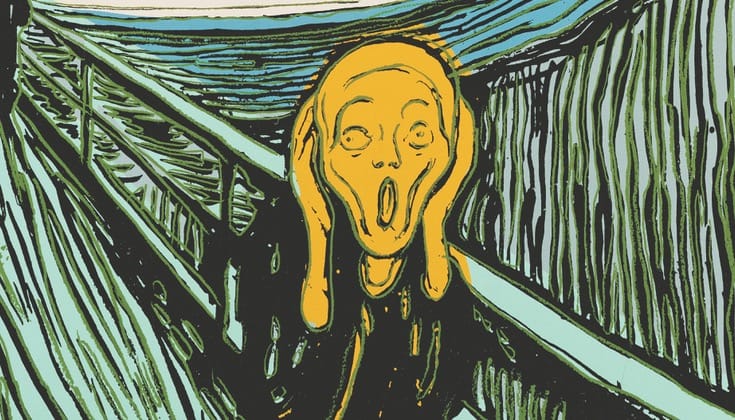

It is easy to become so consumed by your fears for this world that you lose your balance. It is hard to think about the challenges facing our planet and not feel overwhelmed.

It seems as if we humans never learn. Instead, we keep perpetuating the same dysfunctional behavior in every generation. Only now, we have the capacity to create havoc on a global scale, to the extent of threatening the continuation of life on this planet. We not only continue to rely on age-old habits of violence, greed, and deception, but we have put these habits on steroids.

On an individual level, we can’t seem to stretch beyond the narrow bounds of self-interest and looking out for number one. This focus on ourselves feeds our fear and makes us susceptible to manipulation. It feels as if the worse things get, the more frantically we apply approaches that have never worked.

Because these times happen to be our times, for us they seem uniquely difficult. But it is hard to imagine any time that has not seemed troubled to the people who were experiencing it.

To the extent that our world is dominated by hatred, greed, and ignorance, known in Buddhism as the three poisons, it is because we have collectively made it so.

The Buddhist notion of samsara implies that all times are troubled. Not only that, but the troubles we complain about are the very troubles we ourselves create and perpetuate. So to the extent that our world is dominated by hatred, greed, and ignorance, known in Buddhism as the three poisons, it is because we have collectively made it so.

The idea of samsara could be taken as an extremely pessimistic view of things. But it could also be a quite liberating message.

It is liberating to drop the fantasy of there being a more perfect world, somehow, somewhere, and instead accept that we need to engage with the world as it is. It is our world, it is messy, but it is fertile ground for awakening. It is the same world, after all, that gave birth to the Buddha.

It is easy to be overwhelmed by all the problems in this world. You may already be overwhelmed by the problems in your own life. On top of that, you are continually bombarded with news about political, humanitarian, and environmental problems.

There seems to be no end of problems. While you are worrying about human trafficking, you get an email about starving giraffes in Indonesia. When you are distressed about racial hatred, you hear about the latest famine. While you are learning about nuclear proliferation, a politician says something outrageous. It never lets up and it is hard to catch your breath. The continual bombardment of bad news can infiltrate so deeply that it subtly infuses everything you do.

Ironically, it is only this disappointment with the world—with human beings and their stupidity, and with ourselves—that provides a powerful enough motivation to change. Traditionally, reaching the point where you see through the futility of samsara is considered an essential breakthrough on the spiritual path.

For many people, it is the experience of disappointment in its many forms that leads them to the dharma and to the practice of meditation.

Disappointment is a great instigator. From it, positive seeds of change can emerge. When we feel genuine remorse about our own contribution to the samsara project, it strengthens our longing for an alternative and our determination to find a better way to live.

You could go on for years, drifting along in your complacency, not wanting to let the world’s pain touch you. But when it does, you are primed for transformation. Your willingness to feel the suffering of samsara begins to draw out from you a bright stream of compassion for all beings.

When you get news of something disturbing, it is good to pay attention to the shape of your reaction. If you hear about a suicide bombing in Lahore, for instance, what is your immediate response?

You could pretend none of this is happening, that it has nothing to do with you. But because you are human, like it or not, you cannot help but care about such things.

You need to recognize your ability to care and appreciate it for the gift it is. You can actually care about something beyond yourself! You can care about others, you can care about our Mother Earth, you can care about structures of oppression. How amazing that you have not shut down, that you have not given up!

What about when you feel that the intensity of this world is just too much? When you’re caught between freaking out and shutting down?

This is the moment when you need to step back and get some perspective. When you feel your mind/heart filled to the point of claustrophobia with thoughts of disaster, fear, and despair, it is good to bring to mind the many counter examples of human kindness and sanity, which are so easily overlooked.

If you think about it, the degree in which our world is stitched together with loving-kindness is extraordinary. To a surprising extent, accomplishing the simplest daily tasks requires that most people we encounter will be relatively decent, even kind. This network of decency is so close at hand, so mundane and ordinary, that it is mostly invisible to us. Even in the midst of the most dire conditions, there are countless examples of people who still manage to love, share, help one another, smile, and laugh.

When you get news of something disturbing, it is good to pay attention to the shape of your reaction. If you hear about a suicide bombing in Lahore, for instance, what is your immediate response?

Most likely it is one of empathy. You imagine how horrible it must be to witness such a thing. You think about how painful it must be to be killed or injured or to lose a loved one so suddenly and violently. You imagine how it must feel to be stuck in a country at war with no means to get out.

That natural response of human empathy and kindness is tender and raw, and at the same time, it is uplifted and beautiful.

If possible, notice and stay with your empathetic response and get to know it. It is simple and immediate, but it also tends to be fleeting and subtle. It is good to keep coming back to that natural compassionate response to suffering, for it is easily lost in the complexities that follow.

The plot thickens as our innocent and natural response to suffering is captured by ego’s defense mechanisms. That tender response, with its rawness and vulnerability, gets taken over by our emotional habits and fixed views. We are fearful and we want the world to make sense. We are angry and we want revenge. We don’t want to feel the pain of caring, so we feed our negativity as a way to deflect it outward.

You do not need to let your thoughts and reactions run wild. You can interrupt the pattern.

This also unleashes our urge to fix things. We don’t want to keep feeling this way. We want to act! “There’s got to be something I can do to about this right now!” The problem is that often we are in no position to really help.

In response, you could let helplessness overwhelm you, but you don’t have to do so.

You need to accept the fact that you can’t fix everything, much as you would like to.

The world needs help, but our ability to contribute seems so miniscule compared to the many problems facing the planet. The challenges are so overwhelming that we see no way out. What do we do with that frustration?

If you stay with the energy of the impulse to act, you can see that it is a positive irritant. We need a little provocation or creative restlessness in order to connect with what underlies our impulse to act and open up to its message.

So you can take your urge to help as a good sign. But you need to take a clear look at what you really have to offer. You need to start with a self-assessment and a bit of humility.

The great Buddhist teacher Shantideva made the point that if you can do something about an issue, then go ahead and do it. But if you can’t do anything, then acknowledge that and let it go. It doesn’t help to dwell on everything that is going wrong or obsess about wishing you could do more.

It is better to do one small thing that you can actually pull off than to fantasize about all the great things you would like to be able to do but can’t.

Captured by powerful emotions and flurries of speculative thought, we can work ourselves into a frenzy by obsessing about events we have no direct connection with or control over. This is an important pattern to notice. We can see that we are mostly responding to what is in our own head, to our mental chorus of what-if’s. How easily our tender little pebbles of empathy can get buried under a mountain of thoughts.

It is one thing to engage in analysis or try to read the handwriting on the wall so you can respond appropriately to developments in the world. But it is quite another to engage in mental cud chewing, which warps your initial tender response and makes it about yourself.

Notice how obsessive, what-if thinking can take you over, then bring yourself back to the here and now.

It may not seem like it, but when you are stuck in fearful and despairing thoughts, you do have a choice. You do not need to let your thoughts and reactions run wild. You can interrupt the pattern. You can slow down enough to investigate the cascade of thoughts, speculations, opinions, and emotions aroused by hearing about all the troubles in the world.

You can understand more clearly your own particular default patterns, with all their complexities, and bring yourself back to the simple natural arising of care and empathy.

It is possible to walk a path between the extremes of pessimism and optimism.

In order to respond with skill and compassion, you do not need to come to a solid conclusion about the nature of the world. You do not need either to cling to your view of how bad things are, or to close yourself off from whatever disturbs your rosy view of things.

If you look at your own experience from day to day, you can see the shifty quality of such judgments. “I had a good day. It was warm and sunny and I felt great. But yesterday I had a crummy day. It was rainy, I got the flu, and I fell behind in my work.”

In any individual life, there are easier and harder times. Circumstances are always changing. They change slowly and inexorably, and they change suddenly and unexpectedly. Often we see our own hand in the circumstances we experience, and sometimes we are blindsided by situations beyond our control.

When things are going relatively smoothly, it is easy to become complacent and assume that our good fortune will automatically continue. When things are not going well, we also assume that nothing will ever change, and we succumb to defeatism. In both cases we take whatever we are experiencing currently and project it into the future, selectively recalling past experiences that reinforce our view of the way things are.

Our struggle to pin down our living on-the-spot experience of life is futile. We may attempt to get a grasp on life, to pin it down or make it manageable in some way, but it is hard to see beyond the circumstances and mood of the moment.

There seem to be only two alternatives: the glass is half full or the glass is half empty. But a glass with water up to the midpoint is not making a statement either way. It is neither half full nor half empty. Neither is it both half full and half empty. Such a water glass is not elated by being half full, nor discouraged by being half empty. It just is: a glass with water in it.

The world just is. It is not a this-versus-that, good-versus-bad world. It is an interdependent world.

This interdependent world is the dancing ground of bodhisattvas, who thrive in the dynamism of life. By recognizing that every sorrow invites a fresh compassionate response, the bodhisattva path gives us a much broader perspective on our situation. Bodhisattvas are the ones who see the depth and breadth of suffering and confusion most clearly, yet they place themselves right in the midst of it.

I have often wondered: how can bodhisattvas sit there so elegantly and smile? It may be because they have learned that no matter how bad things become, it is possible to change one’s attitude on the spot. The flow of compassion cannot be interrupted. In fact, with each new crisis, its flow is increased.

At any moment, as my teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once told me, “You could just cheer up!”