After graduating from Parsons School of Design in New York City, the artist Rima Fujita was introduced to the most prestigious art dealers in the New York art world. This seeming good fortune came with a dark cloud. She was deceived, dealers stole her work, and she experienced sexual harassment. Even though she was making good money, she was miserable. She began to wonder, “Is this all my life will be?”

In the late 1990s, Fujita had a dream that would answer that question. A voice said to her, “You must help Tibet!”

Fujita didn’t even know where Tibet was, so she began researching. Immediately, she was moved by the plight of Tibetans under Chinese rule. She also felt helpless. “What can I do?” she wondered. “I’m just an artist. Not a movie star. Not a billionaire.” Still, she listened to the dream.

“I’m not psychic, but I’ve always had a relationship to my dreams,” she tells me in an interview. “It was a commanding voice that you would not ignore.”

This dream changed the entire course of Fujita’s life—her art, her spirituality, her mission in the world.

When I meet up with Rima Fujita on Santana Row in San Jose, she leads me to a small redwood grove near her apartment where the tall trees offer a quiet shelter from the busy shopping area just a few blocks away. Fujita loves this calm oasis. “I am a tree lover,” she tells me. “I talk to trees and the moon.”

I feel an immediate connection. Like me, she’s intuitive and empathetic. She trusts her instincts. Like me, she’s a practicing Buddhist in the Tibetan tradition. She also uses a black surface as the base for her artwork and wants to offer her talents to benefit others. I’m taken with how much we have in common. Until we get to her apartment.

Unlike my modest place, hers overflows with beautiful items that showcase the artistry of the craftspeople who made them. The coffee table was special-ordered from India. The hand-painted floral chest is a rare find from an ashram store. Marble craftsmen in Jaipur, India, made the little statues of Lord Ganesha and other deities. In the front of her meditation room is a large open cabinet custom-made by a monk. A thangka of the twenty-one Taras, a gift from one of her teachers, is autographed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The meaningful objects provide an uplifting support for her practice.

Order comes naturally to Fujita. In her workspace every tool and drawing implement is in its own place, and before creating anything, she clears her mind and centers herself. Her controlled environment and work ethic have a lot to do with her upbringing. Her ancestors were samurai and the Bushido code was part of everyday life. From an early age, her grandparents taught her the virtues of that code—justice, honor, honesty, respect, courage, loyalty, self-control, politeness, and compassion.

Rima Fujita was born in Tokyo. Her father was the CEO of a large corporation, and his work required the family to move to New York City when she was fifteen. There, her parents enrolled her in a prestigious prep school. After ten years, her parents returned to Tokyo, while Fujita stayed in New York.

Despite all her privileges, she recalls her childhood as less than idyllic. “As an only child,” she says, “I spent a lot of time alone, drawing and creating things. I spent many hours daydreaming.”

At the prep school, there were few students of color, and Fujita struggled to fit in. She didn’t speak much English and was intimidated by her classmates’ wealth. She also experienced racism, not only from other students, but from her teachers as well.

In the midst of this painful environment, though, a comment from a fellow student changed Fujita’s attitude and gave her the self-confidence she needed. “A boy asked me about Kabuki,” she tells me. “I couldn’t answer his question, because I did not know anything about this traditional Japanese form of theater. He said to me, ‘You’re from Japan, but you don’t know anything about your culture!’ and walked away.

“This embarrassing event made me realize something important. You must be proud of where you come from. I stopped trying to fit in, and I became comfortable with who I was. Then I was able to make friends naturally.”

From a young age, Fujita knew she was meant to go into the arts. Her talent and determination convinced her parents, who were at first skeptical. Parsons, where she blossomed in a diverse and creative environment, proved to be a valuable choice. She was popular with the students, many of whom came from widely different backgrounds, races, and cultures.

“The diversity fascinated me and inspired me,” she says.

At art school, Fujita excelled in line drawing, but she felt that her drawings had no character, that they were boring. As an alternative, she started to embrace the Japanese aesthetic of wabi sabi—finding beauty in imperfection. She wondered how she could illustrate without exercising precise control. Drawing on black paper was the answer that came to her in her second year at Parsons.

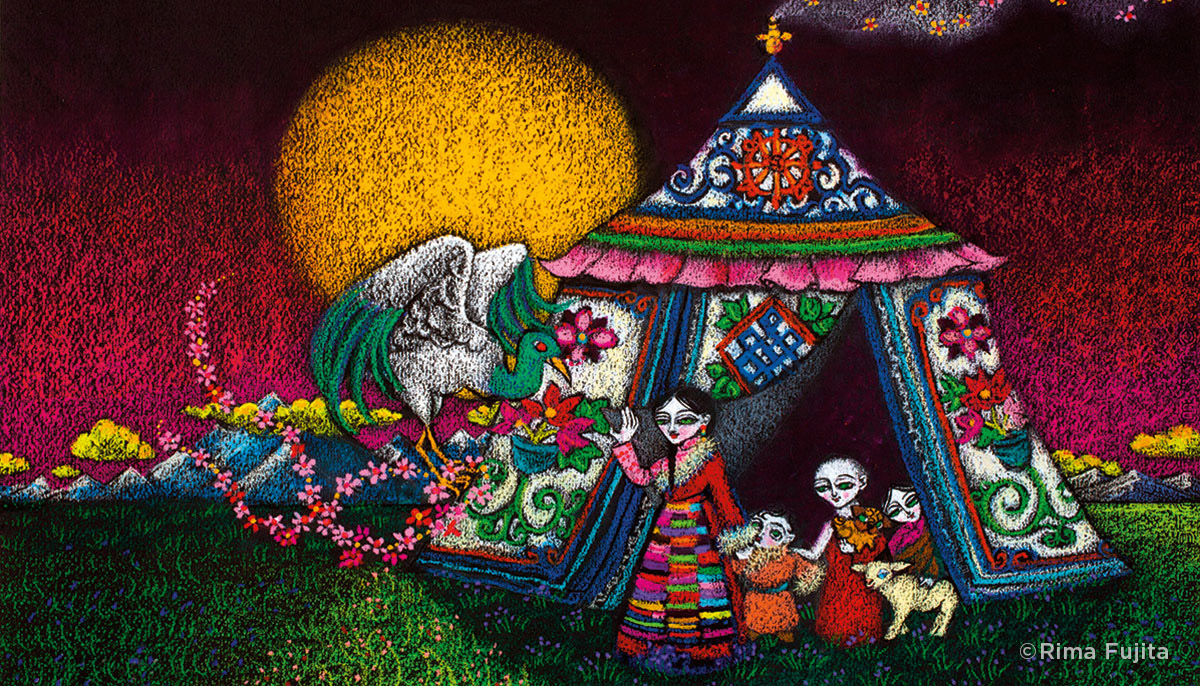

The textures are rough and imperfect. The black outlines emerge only when the colors and shapes are filled in. “It’s a deconstructive process,” she explains, “like shedding light on something that’s already there. With oil pastels on black paper the lines look unique, and it’s easier for me not to control every stroke. Beauty is born when you can let go of control while you are controlling.”

After Rima Fujita began to follow the directive from her dream, she started meeting Tibetans. Her first Tibetan friend described the plight of Tibetan children in the refugee camps in South India: the kids have very little food or clothing, not even a pencil. Fujita then saw how she could fulfill a need in the Tibetan community: by making picture books in Tibetan, she could help them preserve their language. Filled with this determination, she met many people who were prominent supporters of the Tibetan cause, including Robert Thurman and Richard Gere.

Fujita’s art began to take on a new sense of purpose. She now understood the reason why she created—to use her talents as a way to help others. “Until then, art was my goal,” she tells me. “But after that dream, art became my tool toward a bigger purpose. Realizing that was the happiest moment of my life.”

Soon after Fujita started serving the Tibetan community, she took a Tibetan Buddhism class. It was a transformative experience.

“I feel fortunate to have encountered Buddhism, which wasn’t something that came to me from my parents,” she tells me. “My Tibetan Buddhist practice changed my life, not just the way I live, but also in what I use my art for, why I create it.” Compassion became Fujita’s main focus.

She considers His Holiness the Dalai Lama her principal teacher. She has also studied with many other teachers, including Garchen Rinpoche, with whom she felt a strong connection the moment he stepped out of a car and walked toward her in Ladakh, in the middle of nowhere. Fujita pays attention to such auspicious coincidences.

She recounts for me another unusual occurrence that changed the course of her career. “One summer,” she says, “I’d just returned to New York City from Tokyo. I was sick, and I didn’t have enough U.S. dollars to take a cab from the airport. Suddenly this woman appeared and gave me the exact amount of money I needed. Then she disappeared. No one in the room saw her. I forgot about it until I was in Rizzoli Bookstore and a book literally fell in front of my feet. It was a collection of stories of people who were helped by strangers. One of the stories was about a woman who needed help on a plane, and this gentleman helped her and disappeared before she could thank him. It was just like my experience with the woman and the money for the cab.”

That incident in the late 1990s occasioned another major turning point for Fujita. Up to that point, she’d been drawing whatever she saw in the external world, sketching people everywhere and making drawings from the sketches. But after that day at JFK Airport, she stopped sketching and started drawing and painting her visions instead. The finished artworks appear to her, whether in dreams or in her waking life, before she actually creates them.

“I have to draw my inner spiritual world, not the one I see outside,” Fujita says, “because the really important things are invisible—not the material things, but the energy, the kindness of human interaction.”

Rima Fujita began writing and illustrating children’s books for Tibetan refugee children in 2001. She’s given more than fifteen thousand book copies to children in exile, and she donates her royalties to the Tibetan Children’s Villages schools in Dharamsala and to Indian-government-run Tibetan schools all over India, plus the Ngoenga School for Tibetan Children with Special Needs in Derahdun, India; Delek Hospital in Dharamsala, India; and more.

The Dalai Lama wrote the foreword to all her books that are published in both Tibetan and English. They include Wonder Talk, a Tibetan folktale about wisdom, and Wonder Garden, a true story illustrating His Holiness’ compassion. Another book, Save The Himalayas, addresses environmental awareness.

In addition to these publications, Fujita drew books for young adults in cooperation with the Health Department of the Tibetan Government in Exile. TB Aware addresses how to prevent tuberculosis, which occurs at high rates in the Tibetan diaspora, and Rewa is about sexual health. Tibetan Identity was Fujita’s own idea. Tibetans are spread out all over the globe, held together mainly by their reverence for the Dalai Lama and his spiritual leadership. Concerned about what might happen to the Tibetans once he’s gone, she wanted to make a book that helps Tibetan children rethink their identity and be proud of who they are.

When Fujita was first offered an audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, she felt she wasn’t ready. Ten years would pass before she accepted an official audience. After that, she saw him two or three times a year.

In 2017, one of His Holiness’ representatives asked Fujita to make a picture book about the Dalai Lama. She was elated. “It was the biggest honor in my life,” she says. Fujita chose to have it published by Wisdom Publications, which is run by Buddhist students and scholars in the Tibetan tradition. Initially she wasn’t sure how to approach the project. Then His Holiness appeared to her in a dream. Taking her hand gently in his, he smiled at her. After that, she had no trouble writing the story.

The Dalai Lama’s biography is well known, but the uniqueness of The Extraordinary Life of His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is in the way Fujita tells the tale, what she chooses to highlight, and in the design. The Dalai Lama’s loving, kind spirit is evident in the colorful pastel illustrations drawn on black canvas.

The stories illuminate His Holiness’ compassion, as well as his escape from Tibet, his exile, his commitment to humanity, and his resolve to serve the Tibetan people.

The book includes touching details about the Dalai Lama’s childhood. Recognized as the fourteenth Dalai Lama and taken to Potala Palace at the age of four, he had a hard time adjusting to a monastic setting. He was lonely, with only cooks and sweepers for friends. A mouse who snuck in every evening to drink butter from the lamps was a welcome companion to soothe his anxiety.

As I look at the book Fujita has handed to me, one of the drawings especially catches my eye—a nest of open-mouthed baby birds in a tree surrounded by cherry blossoms. In his eighties, His Holiness enjoyed his morning walks in his garden in India. Noticing a newborn baby bird being harassed by wild monkeys, he asked his bodyguard to stand by the tree and watch over the birds.

I ask Fujita about another project: her Oracle cards. Each of the twenty-seven cards is drawn in bright pastel colors over a black background, the edges trimmed in gold. She created the cards during a difficult time a couple of years ago, because she wanted to make something to help people going through similar crises in their lives.

Although she exhibits and sells her work internationally, Fujita doesn’t make things solely to sell. The art has to mean something to her. “You have to have passion,” she tells me.

As for her next project, Fujita says she hasn’t gotten the calling yet. By now I completely understand what she means. I leave her place full of gratitude for our auspicious connection. Meeting Fujita and learning about her art, her spiritual journey, and her philanthropy has affirmed my own resolve to follow my instincts and let compassion guide my choices. Her creative process and spiritual path offer an example of how Buddhist artists can integrate these two practices. Like Fujita, may we all recognize and honor our unique gifts and use them to benefit sentient beings.