Pamela Ayo Yetunde: How do you understand the particularities of Black people’s suffering in the United States?

Jean Marie Robbins: I understand them as an intentional device to maintain an enslavement mentality, in order for the people on top and in power to do as little as they need to and reap the benefits of very inexpensive labor, if not free labor. That was intentional from the beginning, and it took time to take root. Now it’s so deeply rooted that it’s rooted in my own consciousness, and I have to work intentionally against the idea that I’m indebted and I have to always pay my way and pay twice as much, just to belong and to stand alongside people in white bodies.

Pamela Freeman: Jean, you said it very clearly, and I would echo what you said. We’re still living in a post-Confederacy. There is this whole thing of taking away of our rights and chipping away at everything we have in order to keep us controlled. Think about slavery. Our children were taken away from us; marriage was something that couldn’t happen for us. Now they’re trying to eliminate public schools, trying to eliminate everything that can empower us. I see what’s happening in this country. It seems to be getting worse, not better.

Ramona Lisa Ortiz-Smith: I didn’t want to deal with race when I first started practicing. I just wanted to sit and meditate, but there is a force in meditation that brings up the truth. So, I’m rediscovering and peeling back the layers to figure out my understanding of blackness in America. It’s an oppressive system that was created to oppress Black people and other peoples who were not part of the dominant culture. And it still exists, it still persists.

I was writing something the other day about people wanting us to forget about slavery because it was a long time ago. But when I sat down and looked at it, I’m only maybe three generations out of slavery on my mother’s side, and maybe four generations out on my father’s side. Then I look at what’s happening today.

What really gets me is the economic oppression—the hundreds of years that we worked as enslaved Africans, without any compensation, with barely any food, while the ways we had of supporting ourselves culturally were stripped from us. Given all the time we were building wealth for this country and for the world, to have it turned around—to say that it’s my fault that I’m in this economic situation—is crazy. If the economic system doesn’t change, the situation is not going to change.

We’ve tried over the years to have our own this, that, or the other, then it gets destroyed, blown up, taken, stolen again. I’ve been thinking, “Where in the world can I live outside of the system?” because I’m tired. What countries have not been colonized? Where is there not racism against this Black woman’s being? We’ve got to change the economic system, destroy it completely—in some peaceful way.

Victoria Cary: We are a diverse people, so it’s difficult to generalize, but what comes to mind is our exhaustion at having to still fight for equality, equity, and for our lives.

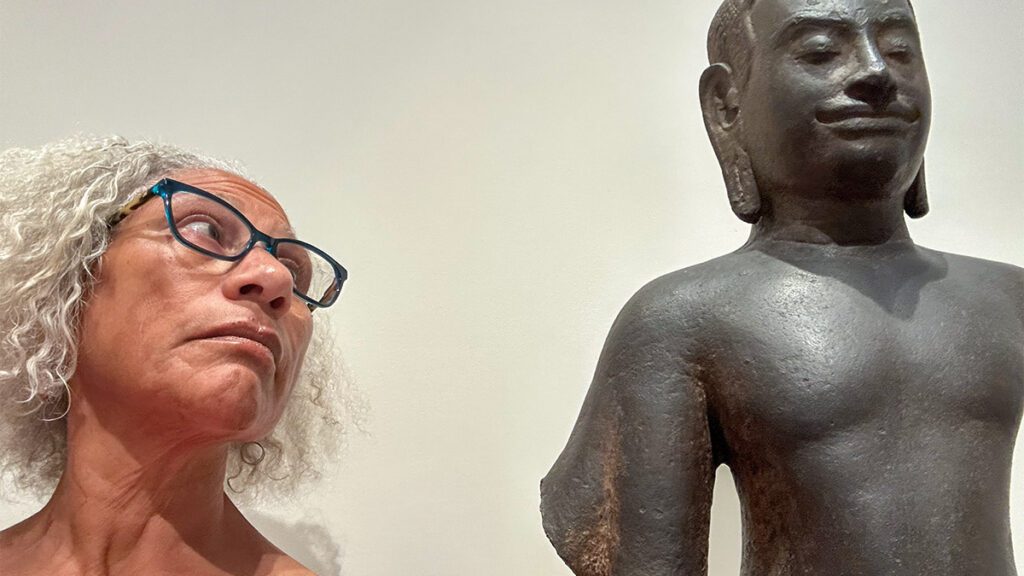

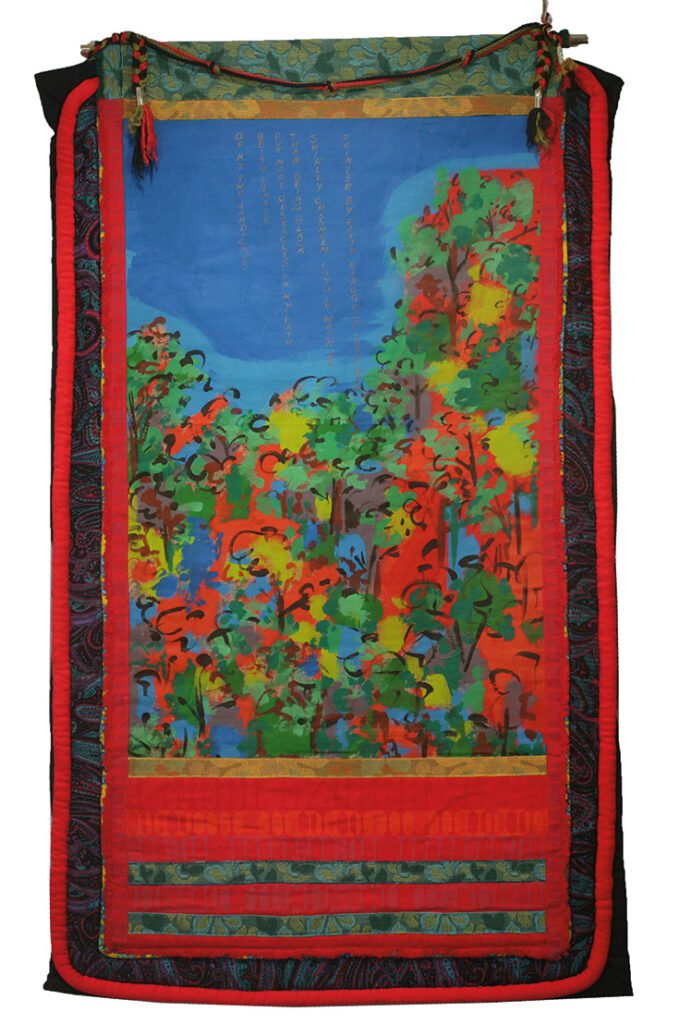

“Feminist Series: Of My Two Handicaps #10 of 20,” 1972 © Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York / CARCC Ottawa 2024

Given the particularities of the suffering of Black people in the United States, how can Buddhist practice help?

Ramona Lisa Ortiz-Smith: The dharma is a healing force. It’s medicine for the soul. That is why I do it. I practice because everything that is a part of life is in the dharma—the truth of the nature of things. It is a language that I understand, I think, from way back to all of my different indigenous roots. It is the language of what is present, what is real.

Practicing the dharma allows me to contemplate, discover, and reflect on ways that I might be able to live this life with more ease and peace, love myself, forgive myself, love others, forgive others in a way that includes forgiving them for racism. The dharma is medicine; it provides me with a salve, which to me are the teachings that, when practiced and applied to my life, support the healing of my being. As a practitioner, I have to let go of my views, and I have to reflect on my conditioning and the conditioning of others. It’s deep when you really do that. The dharma says that this is what you need to find liberation and this is how you do it, so go see for yourself. I can bring the dharma to bear on racism or on anything else.

Pamela Freeman: I agree that the dharma is medicine—it’s healing. Before I practiced the dharma, I felt really disconnected. It has helped me to not be agitated, to listen to people better, to be kinder to myself and other people. It’s helped me to be quieter, and it’s given me a lot of hope. When I’m in meditation or walking or thinking or listening to a dharma talk, I feel so grateful that I’m alive.

The dharma has helped me to be able to deal with some white people, because, before I practiced, I was just done. Now I can be with them and not feel so angry. It’s helped me to not be so reactive, and I think that’s why Black people need the dharma. We can be really mean and nasty to ourselves. This practice helps me give myself a break when I make mistakes.

Jean Marie Robbins: I live in Chicago and I belong to Shambhala Chicago. I came to Shambala about ten years ago in a very resistant mode, but the minute I heard the instructors say that meditation builds confidence in our basic goodness, I was hooked, because as a Black person, I’d never before heard that I was basically even acceptable, not to mention good.

Buddhism’s first noble truth is that there is suffering. Regarding the particularities of the suffering of Black people, I have coped much of my life by expecting to suffer racial harm and expecting white people to look at me in a negative way. Now, I’ve shifted my idea of suffering, and I ask myself, “What can I learn here?” One of the things I’m learning to do is to release what I imagine people are thinking about me—that’s just a thought. When I pause, I’m letting go of that flood of negative talk. Of course, it floods right back. It’s normal to have negative self-talk, so learning to let it go is a process—it doesn’t happen overnight.

I think the idea of no self is such a perplexing idea, but it’s one of the things that has helped me recognize this idea of identity as a trap. In a dharma setting, we can talk about that and really explore what it means to shackle ourselves with the idea that we’re limited to this identity, an identity that is defined by our society as something terrible, when really, it is our incredible resilience and resolve to survive that has made this country.

From Dr. Sheila Walker’s anthropological study of African descendants, especially in the Americas, I’ve learned that Afro-diasporans made the modern world by impacting music, science, business, food, agriculture, sports, and many other fields. Learning this has totally shifted my thinking about what we’ve contributed, what we’re capable of, and what I’m capable of.

Victoria Cary: Dharma is a path toward freedom. The dharma can be that for Black folks, too. It’s certainly been that for me.

If you could give one piece of advice on how to experience liberation, what would that be?

Victoria Cary: Be curious and acknowledge reality with compassion.

Ramona Lisa Ortiz-Smith: My advice would be to cultivate embodied stillness and empowered silence. When you choose to be silent—and not silenced by the oppressors—when you stay in the present moment with this breath, this body, there is an element of liberation.

Pamela Freeman: Liberation, to me, is believing in yourself. Trust in yourself, in your stillness, and even in your movement. Know that being yourself and believing in yourself is not something above you—it’s inside of you.

Jean Marie Robbins: In building on that, Pamela, I think that connecting with what we really are—with our basic goodness—and accepting all our stumbles and flaws softens us and enables us to connect with others. And that’s where liberation happens in our relationships, not just with others, but also in our relationship with ourselves.

Ramona Lisa Ortiz-Smith: Movement is such a big part of my Black experience. In moving, the mind gets to settle so that we can just be with our truth, connect to the earth, and see the ideas, views, and the conditioning that trap us, that shackle our minds. In embodied movement, there’s freedom.

Jean Marie mentioned the concept of no self. That word and concept has also been used in Buddhist dialogue to mean that race, ethnicity, the ways we identify socially don’t matter. My question to you is, does it matter to the people you serve in your dharma communities that you are Black?

Ramona Lisa Ortiz-Smith: Yes, it matters. Before I can actually let go of my identity, I have to embrace all of who I am—all of my life, all of my experiences, all of my views. This way, I get to know all these different facets of my identity and understand where they came from, how they’ve shaped me, and how society persists with identifying me with some of them.

But “no self” doesn’t mean that I don’t exist. Like Joy DeGruy [author of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing] says, in this skin, it’s a different experience. So, it is true that I look like this—I am Black—and my experience in this world and in meditation and dharma communities is completely different because of it. I have to walk through this world in this skin; I can’t leave home without it. Therefore, I have tangible, visceral experiences as a dharma practitioner and teacher in this skin that are different than those who are not people of color and do not live in this skin. It causes challenging conditions in the practice and in practice communities because I and other people believe that I have a self that is “Black.”

Jean Marie Robbins: Yes, it absolutely matters that I am Black! I feel like my showing up in my sangha is a practice that I impose on my white colleagues. It is a practice for them to manage their sense of anxiety or curiosity or resistance or whatever.

My Black body does get a different reaction from others. On an absolute level, there’s no self, and I can see that. I can relinquish the habits that confine me to this sense of identity. I can be totally free, but I am in this body, so I probably am not going to relinquish all these habits until I leave my body.

Victoria Cary: That statement—that race and other identities don’t matter—is just not true. Race matters, identities matter. It matters to me, and it matters deeply to those Black folks I serve. It matters because if you don’t acknowledge my race, my gender, my sexual identity, you don’t acknowledge me, my suffering, or my humanity. The dharma is about reality, and the reality is that race-based discrimination is still happening today in this country.

Pamela Freeman: Delaware Valley Insight is mixed—mostly white. People tell me it’s important that I’m there, and my experience is very different from the white members of my group. With the people of color group, my presence gives them hope. When I see Black dharma teachers and leaders, I want to cry. When I started this practice, there were two Black people, and now there are many of us. I think we give each other hope.

As we talked, I felt myself falling in love with you all, and that has to do with feeling like I was receiving a transmission of deep loving-kindness, compassion, and care. You all have committed yourselves to take care of people like me, and I felt myself leaning in for that care. Thank you.