Rebecca Solnit is certain of only one thing—that hope includes uncertainty. “We don’t know what’s going to happen next, and that gives us room to act,” she says. “Hope is active engagement with uncertainty and the possibilities that it holds.”

Solnit is best known as an important feminist writer and activist. Her 2008 essay Men Explain Things to Me is credited with launching the term “mansplaining.” But as an award-winning journalist, historian, and activist, her work spans many genres, disciplines, and causes: landscapes, criticism, human rights, technology, indigenous peoples, gender, visual art, and climate change.

When I ask Solnit how she describes what she does, she says, “My work has often been about connections between things seen as far apart or disparate—connections to cross fields in disciplines and cross times in cultures. I try and encourage people. I take interest in pleasures and possibilities that are already all around us. I try and connect the present, past, and future in how I tell stories. I try to look for the alternatives and the overlooked entrances and exits.”

Writing is saying to no one and to everyone the things it is not possible to say to someone. -The Faraway Nearby

Solnit learned to read the first week she attended school. “By the second semester, I realized that somebody got to write the books, and I made my final career decision then,” she says.

She grew up in Novato, California, north of San Francisco, and had a violent childhood. “Every place was safe except home,” she remembers. “To the north there was all this space and landscape, and to the south there was a really great public library. So I took refuge there, and I’m still spending a lot of time in versions of those two places.”

Solnit’s teenage years were no better. She was ignored during her parents’ tumultuous divorce and experienced high school as a “behavior-modification center” where she did not fit in. She dropped out at fifteen, got her GED, and started college at sixteen, with no encouragement except her own ambition.

Deciding that what she really needed was to leave everything associated with home behind her, Solnit moved to Paris for a year. But in this city where the culture and history are so prominent, she was struck by the feeling that her home, California, deserved the same exploration and celebration, and she wanted to be the person to write those words. She returned to the U.S. and earned an English degree at San Francisco State University, where, she says, she learned “how to read but not to write.”

When she went to UC Berkeley journalism school, she again had the experience of not fitting in, this time because of her involvement in the punk scene, which she described to The Daily Beast as “wonderful, because it was for nerds and misfits and weirdos and people who were willing to embrace something that was for outsiders, not insiders.” The familiar feeling of not being “one of” was a theme she would later embrace in her writing.

After publishing a few pieces in her early twenties, Solnit began to understand the power of stories. “We think we tell stories, but stories often tell us, tell us to love or to hate, to see or to be blind,” she writes in The Faraway Nearby. “Often, too often, stories saddle us, ride us, whip us onward, tell us what to do, and we do it without questioning. The task of learning to be free requires learning to hear them, to question them, to pause and hear silence, to name them, and then to become the storyteller.”

When she ended up on unemployment, Solnit had to ask herself some hard questions. She didn’t yet have confidence in her writing and assumed it would be a side project while working at other jobs. Yet she was starting to realize that her own struggles to be seen and heard could serve her voice as a writer, and in turn she could give voice to those facing similar challenges, especially other women. She decided writing was going to be her path, even though it wasn’t going to be easy.

“One of the things about being a girl is that, often, no one encourages you to be ambitious,” Solnit recounted in an interview with Rookie magazine. “I got to rebel by succeeding, and it surprised everyone, including myself.”

“Hope is not about what we expect. It is an embrace of the essential unknowability of the world, of the breaks with the present, the surprises. Or perhaps studying the record more carefully leads us to expect miracles—not when and where we expect them, but to expect to be astonished, to expect that we don’t know. And this is grounds to act.” -Hope in the Dark

Now one of the country’s most influential progressive voices, Rebecca Solnit has written seventeen books, numerous essays, and daily social media commentary on feminist, social justice, and environmental issues. As a contributing editor to Harper’s magazine, she is the first woman to regularly write the “Easy Chair” column. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Lannan Literary Award, and a National Book Critics Circle Award. Her book Hope in the Dark was reissued in 2016, and in May of 2017, her LitHub piece “The Loneliness of Donald Trump” quickly went viral. (“Is this the best piece ever written about Donald Trump?” wondered The Philadelphia Inquirer.)

Hope is an essential part of Solnit’s work, and she has come to see that uncertainty is integral to hope. Solnit says that exploring hope requires an investigation of its other side—despair, which she views as certainty grounded in the negative. She hears despair expressed often, in statements such as “We don’t have any power,” “It didn’t change anything,” and “Nonviolence doesn’t work.” The implication is that a victory that isn’t final isn’t a victory at all.

To counter that despair, Solnit illuminates the beauty, joy, and victories that activist movements, and society at large, have already achieved. “There was this long period when everybody was saying, ‘Oh, feminism failed,’” she says. “I say, ‘Hey, we’re undoing five thousand years of patriarchal culture. Don’t be so shocked that we didn’t finish the job in fifty years. Just look back fifty years to see an almost unrecognizably misogynist landscape in which we didn’t even have concepts like marital rape, sexual harassment, date rape, or terms like ‘glass ceilings’ and ‘microaggressions.’ There’s a huge amount of language that’s been developed to describe the realities of discrimination.”

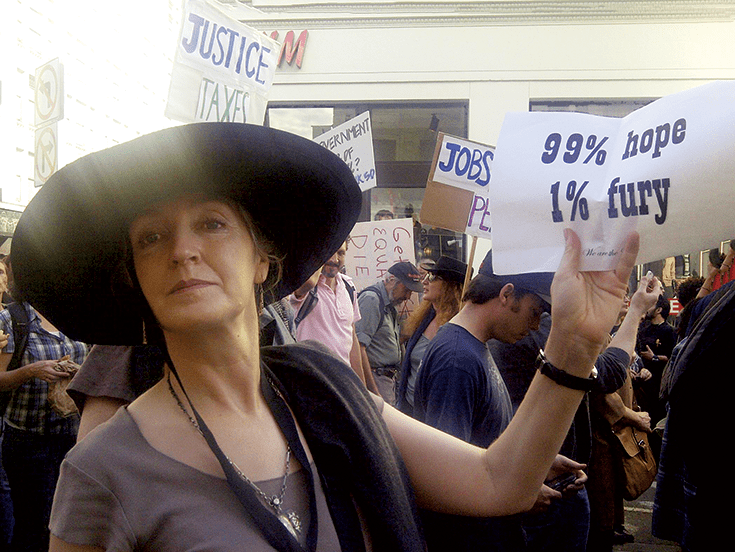

Solnit highlights “amazing movements like Black Lives Matter, started by black women; Idle No More, started by indigenous women in Canada; and a wonderful new generation of young feminists who are not intimidated into trying to be nice and placating and who are fearless in telling it like it is. Young people are rejecting these tidy, firm gender boundaries that limit who each of them and all of us can be. There are the victories of same-sex marriage and the growing strength of a climate movement that wasn’t really much to write home about ten years ago and is now effectively challenging pipelines, fracking, mining, coal plants, and different pieces of the climate picture.”

“The coolness of Buddhism isn’t indifference but the distance one gains on emotions, the quiet place from which to regard the turbulence. From far away you see the pattern, the connections, and the thing as a whole, see all the islands and the routes between them.” -The Faraway Nearby

Rebecca Solnit doesn’t label herself a Buddhist. She likes the term “bad Buddhist,” which she heard poet Gary Snyder use for people who don’t sit every day, follow the rules, or observe all the precepts perfectly. It’s an approach, she says, in which “Buddhism is your guiding star, not the planet you live on necessarily every day.” For her, formal meditation is not the only way to practice. “Practice is how you’re interacting with everything all the time,” she says.

Solnit’s journey into Buddhism was not straightforward. “I had a fairly nightmarish father, but he was interested in Zen Buddhism,” she recounts. “I actually went to Green Gulch Zen Center with him a few times as a kid, and I have fond memories of the zendo, that beautiful wooden barn space. Then my older brothers had this friend who became kind of a creepy stalker who was also very into Buddhism. These not-so-great men really put me off Buddhism until I realized they didn’t represent what Buddhism is.”

Solnit says that living in the Bay Area, Buddhism surrounds her. “It’s not like some places in the U.S. where it’s still this exotic Eastern thing. I live in a city where there’s almost as many Asian people as white people, where every kind of Buddhism has a strong presence and it’s pretty normal.” When she heard a talk by Paul Haller at the San Francisco Zen Center in 2001, she says it was “like a fish hook and I was a fish that was hooked. I thought, ‘This has what I need.’ I’ve been hanging around there ever since.”

Solnit’s Buddhist influences have come from many traditions. “There’s this interesting American project of creating a kind of hybrid Buddhism, not necessarily between the lineages, but more attuned to contemporary American realities,” she says. “Ambient Buddhism” is how Solnit likes to describe the Buddhist themes that appear in her work and inform her understanding of hope and despair.

“Buddhism is acceptance that you’re not totally in control,” she says. “Then there are psychoanalytic and other perspectives where you have to recognize that you contain immense depth and darknesses. You don’t even know yourself completely, so how can you know someone else? We don’t even understand the present, so how can we understand the future? This gives you, on the one hand, a kind of confidence that maybe what we do matters and also helps us see that we don’t know if it matters or not.” She says one of the many joys of Buddhism is its comfort with paradox. “And being given multiple lifetimes is very helpful,” she laughs.

Coming to Buddhism dovetailed with other avenues of thought she was exploring. “The central idea of ecological thinking is that everything is connected to everything else,” she notes. “Buddhism has another version of that truth—non-attachment and compassion—which are really important parts of my political writing.”

Another Buddhist teaching that informs Solnit’s work is that empathy arises through understanding interconnectedness. “Whole societies can be taught to deaden feeling, to dissociate from their marginal and minority members, just as people can and do erase the humanity of those close to them,” she says. “Empathy makes you imagine the sensation of the torture, of the hunger, of the loss. You make that person into yourself; you inscribe their suffering on your own body or heart or mind, and then you respond to their suffering as though it were your own.”

When she encounters those silenced, Solnit recognizes her own experiences of not being heard or being treated as an outsider. Having a public voice through her writing and activism, she feels she has responsibilities to the powerless and silenced. “It makes you feel a commitment to speaking up for the voiceless, as the only legitimate use of privilege is to try and dismantle the inequalities and unfairnesses of privilege.”

“Every woman knows what I’m talking about. It’s the presumption that makes it hard, at times, for any woman in any field; that keeps women from speaking up and from being heard when they dare; that crushes young women into silence by indicating, the way harassment on the street does, that this is not their world. It trains us in self-doubt and self-limitation just as it exercises men’s unsupported overconfidence.” -Men Explain Things to Me

“Women have been silent and silenced in a lot of ways,” Solnit says. She sees both the ground women have gained and how much is still left to do, particularly in the area of violence against women.

She writes in Men Explain Things to Me about two occasions on which she “objected to the behavior of a man, only to be told that the incidents hadn’t happened at all as I said, that I was subjective, delusional, overwrought, dishonest—in a nutshell, female.”

Her work explores how silencing women happens in subtle and extreme ways, while also seeking to understand what drives men to silence women and what makes some women complicit in their own silencing. “How have they been damaged in a way that makes them damaging?” she asks of both. “And how does that get undone?”

In The Faraway Nearby, she writes, “When I was younger, I studied the men I was involved with so carefully that I saw or thought I saw what pain or limitation lay behind their sometimes crummy behavior. I found it too easy to forgive them, or rather to regard them with sympathy at my own expense. It was as though I saw the depths but not the surface, the causes but not the effect. On them and not myself. I think we call that overidentification, and it’s common among women.”

Solnit also celebrates how men are coming to stand beside women in feminism. “I’ve been really exhilarated to see a lot of male feminists out there in the last few years,” she says, “speaking up in a way that I hadn’t seen men speaking up before. They are suddenly rising to say, ‘Oh my God, all these years, we acted like it was women who were supposed to resolve misogyny. It’s like racism was going to be resolved without the participation of white people.’”

“Let’s talk about climate change as violence. Rather than worrying about whether ordinary human beings will react turbulently to the destruction of the very means of their survival, let’s worry about that destruction—and their survival.” -The Encyclopaedia of Trouble and Spaciousness

Rebecca Solnit finds solace, inspiration, and teachings in landscapes both rural and urban, from the beach at low tide to homeless people on the street. She is passionate about spreading awareness of climate change, a cause in which she sees great advancements.

“I’ve seen the revolution and we’re living it,” she says. “It’s slow and broad and deep and has changed innumerable things immeasurably. To appreciate that, you need to be able to perceive subtle, complex, slow things.”

“What does climate change teach us?” she asks. “First, that everything is connected. So we need to have international cooperation, to make our decisions together. We already have everything we need, and we don’t need to burn the fossils from millions and billions of years ago.”

Facing perhaps the greatest existential crisis in human history in climate change, Solnit says we need to ask ourselves, “Who are we in the face of this? What does it ask of us, and how do we respond?” Yet when others despair, Solnit has faith in the power of human awareness, action, and cooperation. “It feels like millions, maybe billions, of people are walking away from a status quo that didn’t serve them, that didn’t describe the world accurately, and are now making more beautiful versions, together.” When others fear uncertainty, Rebecca Solnit sees hope in what can be found when people feel the most lost.