For the nineties, the celebrated Beat rebel advocates “wild mind,” neighborhood values and watershed politics. “Wild mind,” he says, “means elegantly self-disciplined, self-regulating. That’s what wilderness is. Nobody has a management plan for it.”

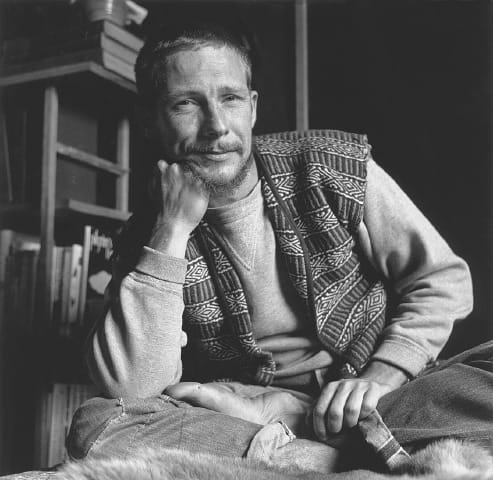

Asked if he grows tired of talking about ecological stewardship, digging in, and coalition-building, the poet Gary Snyder responds with candor: “Am I tired of talking about it? I’m tired of doing it!” he roars. “But hey, you’ve got to keep doing it. That’s part of politics, and politics is more than winning and losing at the polls.”

These days, there’s an honest, conservative-sounding ring to the politics of the celebrated Beat rebel. Gary Snyder, though, has little in common with the right wingers who currently prevail throughout the western world.

“Conservatism has some very valid meanings,” he says. “Of course, most of the people who call themselves conservative aren’t that, because they’re out to extract and use, to turn a profit. Curiously, eco and artist people and those who work with dharma practice are conservatives in the best sense of the word-we’re trying to save a few things!

“Care for the environment is like noblesse oblige,” he maintains. “You don’t do it because it has to be done. You do it because it’s beautiful. That’s the bodhisattva spirit. The bodhisattva is not anxious to do good, or feels obligation or anything like that. In Jodo-shin Buddhism, which my wife was raised in, the bodhisattva just says, ‘I picked up the tab for everybody. Goodnight folks…’ ”

Five years ago, in a prodigious collection of essays called The Practice of the Wild, Gary Snyder introduced a pair of distinctive ideas to our vocabulary of ecological inquiry. Grounded in a lifetime of nature and wilderness observation, Snyder offered the “etiquette of freedom” and “practice of the wild” as root prescriptions for the global crisis.

Informed by East-West poetics, land and wilderness issues, anthropology, benevolent Buddhism, and Snyder’s long years of familiarity with the bush and high mountain places, these principles point to the essential and life-sustaining relationship between place and psyche.

Such ideas have been at the heart of Snyder’s work for the past forty years. When Jack Kerouac wrote of a new breed of counterculture hero in The Dharma Bums, it was a thinly veiled account of his adventures with Snyder in the mid-l950’s. Kerouac’s effervescent reprise of a West Coast dharma-warrior’s dedication to “soil conservation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, astronomy, geology, Hsuan Tsang’s travels, Chinese painting theory, reforestation, Oceanic ecology and food chains” remains emblematic of the terrain Snyder has explored in the course of his life.

One of our most active and productive poets, Gary Snyder has also been one of our most visible. Returning to California in 1969 after a decade abroad, spent mostly as a lay Zen Buddhist monk in Japan, he homesteaded in the Sierras and worked the lecture trail for sixteen years while raising a young family. By his own reckoning he has seen “practically every university in the United States.”

As poet-essayist, Snyder’s work has been uncannily well-timed, contributing to his reputation as a farseeing and weatherwise interpreter of cultural change. With his current collection of essays, A Place In Space, Snyder brings welcome news of what he’s been thinking about in recent years. Organized around the themes of “Ethics, Aesthetics and Watersheds,” it opens with a discussion of Snyder’s Beat Generation experience.

“It was simply a different time in the American economy,” he explained when I spoke to him recently in Seattle. “It used to be that you came into a strange town, picked up work, found an apartment, stayed a while, then moved on. Effortless. All you had to have was a few basic skills and be willing to work. That’s the kind of mobility you see celebrated by Kerouac in On The Road. For most Americans, it was taken for granted. It gave that insouciant quality to the young working men of North America who didn’t have to go to college if they wanted to get a job.

“I know this because in 1952 I was able to hitch-hike into San Francisco, stay at a friend’s, and get a job within three days through the employment agency. With an entry level job, on an entry level wage, I found an apartment on Telegraph Hill that I could afford and I lived in the city for a year. Imagine trying to live in San Francisco or New York-any major city-on an entry level wage now? You can’t do it. Furthermore, the jobs aren’t that easy to get.”

The freedom and openness of the post-war economy made it possible for people such as Snyder, Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lew Welch and others to disaffiliate from mainstream American dreams of respectability. And as Snyder writes, these “proletarian bohemians” chose even further disaffiliation, refusing to write “the sort of thing that middle-class Communist intellectuals think proletarian literature ought to be.”

“In making choices like that, we were able to choose and learn other tricks for not being totally engaged with consumer culture,” he says. “We learned how to live simply and were very good at it in my generation. That was what probably helped shape our sense of community. We not only knew each other, we depended on each other. We shared with each other.

“And there is a new simple-living movement coming back now, I understand,” he notes, “where people are getting together, comparing notes about how to live on less money, how to share, living simply.”

When Gary Snyder points something out, it generally warrants attention: his thinking has consistently been ahead of the cultural learning curve. Nowhere is his prescience more obvious than in “A Virus Runs Through It,” an unpublished review of William Burroughs’ 1962 The Ticket That Exploded.

Snyder regarded Burroughs’ portrait of a society obsessed with addiction and consumerism, “whipped up by advertising,” as an omen. He concluded that Burroughs’ “evocation of the politics of addiction, mass madness, and virus panic, is all too prophetic.”

“We were very aware of heroin addiction at that time,” Snyder explains. “Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Holmes and their circle in New York became fascinated with the metaphor of addiction in the light of heroin, smack. Marijuana was not an issue, but the intense addictive quality of heroin, and the good people who were getting drawn into it, and the romance some people had for it, was a useful framework for thinking about the nature of capitalist society and the addiction to fossil fuels in the industrial sector. It was obvious.”

Many of Snyder’s original arguments addressing pollution and our addiction to consumption have by now become mainstream: reduced fossil fuel dependence, recycling, responsible resource harvesting. Others remain works-in-progress: effective soil conservation, economics as a “small subbranch of ecology,” learning to “break the habit of acquiring unnecessary possessions,” division by natural and cultural boundaries rather than arbitrary political boundaries.

As an ecological philosopher, Snyder’s role has been to point out first the problems, and then the hard medicine that must be swallowed. Snyder has become synonymous with integrity-a good beginning place if your wilderness poetics honor “clean-running rivers; the presence of pelican and osprey and gray whale in our lives; salmon and trout in our streams; unmuddied language and good dreams.”

“My sense of the West Coast,” he says, “is that it runs from somewhere about the Big Sur River-the southern-most river that salmon run in-from there north to the Straits of Georgia and beyond, to Glacier Bay in southern Alaska. It is one territory in my mind. People all relate to each other across it; we share a lot of the same concerns and text and a lot of the same trees and birds.”

Raised in the Pacific Northwest, Snyder grew up close to the anthropomorphic richness of the local Native American mythology, the rainforest totems of eagle, bear, raven and killer whale that continue to appear in school and community insignias as important elements of regional consciousness. It is unsurprising that they-and roustabout cousins like Coyote-have long been found at the core of Snyder’s expansive vision. Literal-minded rationalists have had difficulty with Snyder’s Buddhist-oriented eco-philosophy and poetics. His embrace of Native Indian lore only further ruffled orthodox literary imagination, and in the past his poetry was criticized as being thin, loose or scattered.

As Snyder readers know, the corrective to such interpretations of his work is more fresh air and exercise. Regarding Buddhism, his take is offered simply and efficiently. “The marks of Buddhist teaching,” he writes in A Place In Space, “are impermanence, no-self, the inevitability of suffering and connectedness, emptiness, the vastness of mind, and a way to realization.”

“It seems evident,” he writes, offering insight into the dynamics of his admittedly complex world view, “that there are throughout the world certain social and religious forces that have worked through history toward an ecologically and culturally enlightened state of affairs. Let these be encouraged: Gnostics, hip Marxists, Teilhard de Chardin Catholics, Druids, Taoists, Biologists, Witches, Yogins, Bhikkus, Quakers, Sufis, Tibetans, Zens, Shamans, Bushmen, American Indians, Polynesians, Anarchists, Alchemistsprimitive cultures, communal and ashram movements, cooperative ventures.”

“Idealistic, these?” he says when asked about such alternative “Third Force” social movements. “In some cases the vision can be mystical; it can be Blake. It crops up historically with William Penn and the Quakers trying to make the Quaker communities in Pennsylvania a righteous place to live-treating the native peoples properly in the process. It crops up in the utopian and communal experience of Thoreau’s friends in New England.

“As utopian and impractical as it might seem, it comes through history as a little dream of spiritual elegance and economic simplicity, and collaboration and cooperating communally-all of those things together. It may be that it was the early Christian vision. Certainly it was one part of the early Buddhist vision. It turns up as a reflection of the integrity of tribal culture; as a reflection of the kind of energy that would try to hold together the best lessons of tribal cultures even within the overwhelming power and dynamics of civilization.”

Any paradigm for a truly healthy culture, Gary Snyder argues, must begin with surmounting narrow personal identity and finding a commitment to place. Characteristically, he finds a way of remaking the now tired concept of “sense of place” into something fresh and vital. The rural model of place, he emphasizes, is no longer the only model for the healing of our culture.

“Lately I’ve been noticing how many more people who tend toward counterculture thinking are turning up at readings and book signings in the cities and the suburbs,” he says. “They’re everywhere. What I emphasize more and more is that a bioregional consciousness is equally powerful in a city or in the suburbs. Just as a watershed flows through each of these places, it also includes them.

“One of the models I use now is how an ecosystem resembles a mandala,” he explains. “A big Tibetan mandala has many small figures as well as central figures, and each of them has a key role in the picture: they’re all essential. The whole thing is an educational tool for understanding-that’s where the ecosystem analogy comes in. Every creature, even the little worms and insects, has value. Everything is valuable—that’s the measure of the system.”

To Snyder, value also translates as responsibility. Within his approach to digging in and committing to a place is the acceptance of responsible stewardship. Snyder maintains that it is through this engaged sense of effort and practice-participating in what he salutes as “the tiresome but tangible work of school boards, county supervisors, local foresters, local politics”-that we find our real community, our real culture. “Ultimately, values go back to our real interactions with others,” he says. “That’s where we live, in our communities.

“You know, I want to say something else,” he continues. “In the past months and years Carole my wife has been amazing. I do my teaching and my work with the Yuba Watershed Institute, but she’s incredible; she puts out so much energy. One of the things that makes it possible for us and our neighbors to do all this is that the husbands and wives really are partners; they help out and trade off. They develop different areas of expertise and they help keep each other from burning out. It’s a great part of being a family and having a marriage-becoming fellow warriors, side to side.”

In 1968, Snyder stated flatly that, “The modern American family is the smallest and most barren family that has ever existed.” Throughout the years his recommendations concerning new approaches to the idea of family and relationships have customarily had a pagan, tribal flavor. These days he calls it community.

“I’m learning, as we all do, what it takes to have an ongoing relationship with our children,” he says. “I have two grown sons, two stepdaughters, a nephew who’s twenty-seven, and all their friends whom I know. We’re still helping each other out. There’s a real cooperative spirit. There’s a fatherly responsibility there, and a warm, cooperative sense of interaction, of family as extended family, one that moves imperceptibly toward community and a community-values sense.

“So I’m urging people not to get stuck with that current American catch-phrase ‘family values,’ and not to throw it away either, but to translate it into community values. Neighborhood values are ecosystem values, because they include all the beings.

“What I suspect may emerge in the political spectrum is a new kind of conservative, one which is socially liberal, in the specific sense that it will be free of racial or religious prejudice. The bugaboo, that one really bad flaw of the right wing, except for the Libertarians, is its racist and anti-Semitic and anti-personal-liberty tone.

“A political spectrum that has respect for traditions, and at the same time is non-racist and tolerant about different cultures, is an interesting development. I’d be willing to bet that it’s in the process of emerging, similar in a way to the European Green Parties that say, ‘We’re neither on the left nor the right; we’re in front.’

“One of the things I’m trying to do, and I believe it’s the right way to work,” he says, “is to be non-adversarial-to go about it as tai chi, as ju-jitsu. To go with the direction of a local community issue, say, and change it slightly. We don’t have to run head-on. We can say to the other party, ‘You’ve got a lot of nice energy; let’s see if we can run this way’”

Yet as anyone involved in community activism learns, amicable resolutions are not always the result. “Sometimes you do have to go head to head on an issue,” he agrees, “and that’s kind of fun too. ‘Showing up’ is good practice.”

Snyder remembers a fight some four years ago over open pit mining. “I was the lead person on this one, to get an initiative on the ballot that would ban open pit mining, or at least put a buffer zone around any open pit mine. The mining companies from out of town spent a lot of money and did some really intense, last minute, nasty style campaigning, so we lost at the polls.

“But not a single open pit mine has been tried in our county since then. We understand from our interactions with these people that we won their respect. They were smart enough to see that they may have won it at the polls, but we were ready to raise money and willing to fight. That’s standing up.”

With the growing importance of community coalition-building, Snyder says he is finding it increasingly useful to narrow down his ideas about bioregionalism, or his notion of a practice of the wild, to a shared neighborhood level.

“That’s why I talk about watersheds,” he explains. “Symbolically and literally they’re the mandalas of our lives. They provide the very idea of the watershed’s social enlargement, and quietly present an entry into the spiritual realm that nobody has to think of or recognize as being spiritual.

“The watershed is our only local Buddha mandala, one that gives us all, human and non-human, a territory to interact in. That is the beginning of dharma citizenship: not membership in a social or national sphere, but in a larger community citizenship. In other words, a sangha; a local dharma community. All of that is in there, like Dogen when he says, ‘When you find your place, practice begins.’ ”

Thirteenth-century master Dogen Zenji is a classical Asian voice which Snyder has discussed frequently in recent years. “There are several levels of meaning in what Dogen says. There’s the literal meaning, as in when you settle down somewhere. This means finding the right teaching, the right temple, the right village. Then you can get serious about your practice.

“Underneath, there’s another level of implication: you have to understand that there are such things as places. That’s where Americans have yet to get to. They don’t understand that there are places. So I quote Dogen and people say, ‘What do you mean, you have to find your place? Anywhere is okay for dharma practice because it’s spiritual.’ Well, yes, but not just any place. It has to be a place that you’ve found yourself. It’s never abstract, always concrete.”

If embracing the responsibility of the place and the moment is his prescription, a key principle in this creative stewardship is waking up to “wild mind.” He clarifies that “wild” in this context does not mean chaotic, excessive or crazy.

“It means self-organizing,” he says. “It means elegantly self-disciplined, self-regulating, self-maintained. That’s what wilderness is. Nobody has to do the management plan for it. So I say to people, “let’s trust in the self-disciplined elegance of wild mind”. Practically speaking, a life that is vowed to simplicity, appropriate boldness, good humor, gratitude, unstinting work and play, and lots of walking, brings us close to the actually existing world and its wholeness.”

This is Gary Snyder’s wild medicine. From the beginning, it has been devotion to this quality that has served as his bedrock of practice, his way of carving out a place of freedom in the wall of American culture. In his omission of the personal in favor of the path, he exemplifies the basics of the Zen tradition in which he was trained. The influx of trained Asian teachers of the Buddhadharma to the West in recent years has raised questions about whether the first homespun blossoming of Beat-flavored Buddhism in the fifties actually included the notion of practice. As one who was there and has paid his dues East and West, Snyder’s response is heartening.

“In Buddhism and Hinduism, there are two streams: the more practice-oriented and the more devotional streams,” he explains. “Technically speaking, the two tendencies are called bhakta and jnana. Bhakta means devotional; jnana means wisdom/practice. Contemporary Hinduism, for example, is almost entirely devotional-the bhakta tradition.

“Catholicism is a devotional religion, too, and Jack Kerouac’s Buddhism had the flavor of a devotional Buddhism. In Buddhism the idea that anybody can do practice is strongly present. In Catholicism practice is almost entirely thought of as entering an order or as becoming a lay novitiate of an order. So that explains Jack’s devotional flavor. There’s nothing wrong with devotional Buddhism. It is its own creative religious approach, and it’s very much there in Tibetan Buddhism too.

“Our western Buddhism has been strongly shaped by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Asian intellectuals,” he notes. “D. T. Suzuki was an intellectual strongly influenced by western thought. And the same is true of other early interpreters of Buddhism to the West.

“We came as westerners to Buddhism generally with an educated background,” Snyder continues. “So we have tended to over-emphasize the intellectual and spiritual sides of it, with the model at hand of Zen, without realizing that a big part of the flavor of Buddhism, traditionally and historically, is devotional. This is not necessarily tied to doing a lot of practice, but is tied to having an altar in the house-putting flowers in front of it every day, burning incense in front of it every day, having the children bow and burn incense before it. The family may also observe certain Buddhist holy days such as the Buddha’s birthday by visiting a temple together, and so forth.

“With that perspective in mind, it isn’t so easy to say, ‘Oh well, Jack Kerouac wasn’t a real Buddhist.’ He was a devotional Buddhist, and like many Asians do, he mixed up his Buddhism with several different religions. So it’s okay; there’s nothing wrong with that. You can be a perfectly good Buddhist without necessarily doing a lot of exercises and sitting and yoga; you can be equally a good Buddhist by keeping flowers on your altar, or in winter, dry grass or cedar twigs..

“There’s a big tendency right now in western Buddhism to psychologize it-to try and take the superstition, the magic, the irrationality out of it and make it into a kind of therapy. You see that a lot,” he says. “Let me say that I’m grateful for the fact that I lived in Asia for so long and hung out with Asian Buddhists. I appreciate that Buddhism is a whole practice and isn’t just limited to the lecture side of it; that it has stories and superstition and ritual and goofiness like that. I love that aspect of it more and more.”

Snyder says that at age sixty-five, he’s “working like a demon.” For the past ten years he has taught creative writing at the University of California, leading workshops and participating in the interdisciplinary “Nature and Culture” program. This year will also mark the arrival of his long-awaited sequence of forty-five poems called “Mountains and Rivers Without End,” portions of which have appeared intermittently since Jack Kerouac first dropped word of it in The Dharma Bums.

“I realized I wasn’t going to live forever and that I’d started a lot of parallel projects, with lots of interesting notes to each one, so it – d be a pity not to put all that information to good use. Once ‘Mountains and Rivers’ is done I won’t have to write anything further. Anything after that is for fun. Maybe I won’t be a writer anymore. Maybe I’ll clean out my barn.”

Aging and health are not at issue with Snyder. He works at keeping in good condition and several months ago spent three weeks hiking in the Himalayas with a group of family and friends.

“We trekked up to base camp at Everest, went over 18,000 feet three times, and were seven days above 16,000 feet,” he says with obvious relish. “Everybody was in pretty good shape and I only lost four pounds in a month, so I’m not thinking a whole lot about aging.”

Snyder’s recent journey provided him with insights into the questions of karma and reincarnation, which eco-philosopher Joanna Macy believes may hold special relevance for North Americans. She argues that deeply ingrained American frontier values such as individualism, personal mobility, and independence may contribute to the idea that, “If this is our only one-time life, then we don’t have to care about the planet.”

“The concept of reincarnation in India can literally shape the way one lives in the world,” Snyder notes, “and many Tibetans also believe in reincarnation quite literally. So in that frame of mind, the world becomes completely familiar. You sit down and realize that ‘I’ve been men, women, animals; there are no forms that are alien to me.’

“That’s why everyone in India looks like they’re living in eternity. They walk along so relaxed, so confident, so unconcerned about their poverty or their illness, or whatever it is, even if they’re beggars. It goes beyond just giving you a sense of concern for the planet; it goes so far as to say, ‘Planets come and go’ It’s pretty powerful stuff. It’s also there in classical Buddhism where people say, ‘I’ve had enough of experience.’ That’s where a lot of Buddhism in India starts-‘I want out of the meat wheel of existence,’ as Jack Kerouac says.”

An ecosystem too, Snyder concludes, can be seen as “Just a big metabolic wheel of energies being passed around and around. You can see it as a great dance, a great ceremony. You can feel either really at home with it, or step out of the circle.”

“We are all indigenous,” he reminds us. So it is appropriate that in relearning the lessons of fox and bluejay, or city crows and squirrels-“all members present at the assembly”-that we are promised neither too little, nor too much for our perseverance. This poet, who for so many now reads like an old friend, invites us to make only sense. After all, in recommiting to this continent place by place, he reckons, “We may not transform reality, but we may transform ourselves. And if we transform ourselves, we might just change the world a bit.”