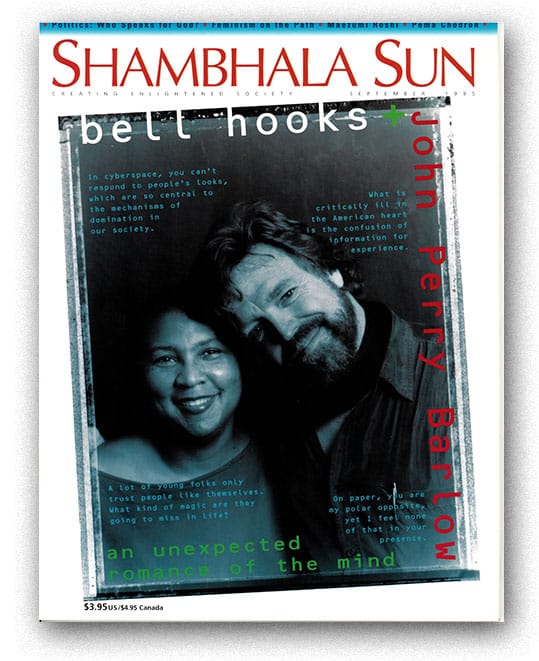

John Perry Barlow: “On paper, you are my polar opposite [bell hooks: iconoclastic feminist, leading African-American intellectual, progressive Buddhist, self-proclaimed homebody], yet I feel none of that in your presence.”

bell hooks: “I’ve never met anyone from Wyoming before [John Perry Barlow: cyber philosopher, retired cattle rancher, world traveler, Grateful Dead lyricist, self-proclaimed Republican]. I sought you out. I wanted to hear your story.”

Love and Sleep

bell hooks: I’m talking to John Perry Barlow.

John Perry Barlow: Out on the street.

bell hooks: …out ON THE STREET!

John Perry Barlow: I was walking past a church in Harlem about a month ago and there was a quote on the sermon board from Proust, of all people, saying, “The journey of discovery begins not with new vistas but with having new eyes with which to behold them.”

bell hooks: Malcolm X always used to say that we needed new eyes. One of the concepts that most turns me on within engaged Buddhism is the idea of what clarity is and of what it takes to get clear.

John Perry Barlow: It takes waking up. I think one of the reasons that Americans are now attracted to Buddhism is because this is a culture in a stupor. The American stupor, hypnotic, hallucinatory condition, has become so pervasive that the idea that one could wake up from it and have clarity or vivid vision is extremely attractive. Of course, saying it don’t make it so.

bell hooks: Well, for me practice makes it so. The practice of mindfulness, the practice of being aware, takes me closer to awakeness. I feel like there is always something trying to pull us back into sleep, that there is this sort of seductive quality in all the hedonistic pleasures that pull on us.

John Perry Barlow: The senses almost exist to dull themselves; it’s as though they want to explore the possibility of space until there’s nothing novel in it. And then go to sleep.

bell hooks: I think that as much as we are a culture that is asleep, we are a culture that is moving away from love. The capacity to love is so tied to being able to be awake, to being able to move out of yourself and be with someone else in a manner that is not about your desire to possess them, but to be with them, to be in union and communion.

John Perry Barlow: My deceased lover and I used to brag about how we’d overcome our narcissism by becoming narcissistic about our relationship. And it did feel that way. I felt much less self-absorbed.

Categories & Intimacy

bell hooks: In this past year when I went around to so many colleges and universities, I found people deeply and profoundly cynical about love. I spent this week re-reading Martin Luther King’s sermon “Strength to Love,” and I was somewhat saddened by the idea that what we remember about him revolves so much around fantasy and dreaming and hope for the future, when there was this real concrete message, particularly during the later period of his life, which was all about love and the rigor of love.

Not easy love but that love which really requires of us the willingness to be dissenting voices, the willingness to stand alone, the willingness to be transformed. He’s constantly stating, “Be not conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewing of your mind.” It seems to me that the process of renewing ourselves is also an act of love.

John Perry Barlow: It seems to me that what we’re here to do is to learn about love in the presence of fear.

bell hooks: I have been thinking about the notion of perfect love as being without fear, and what that means for us in a world that’s becoming increasingly xenophobic, tortured by fundamentalism and nationalism. Even about meeting you—the idea of being able to let fear go so you can move towards another person who’s not like you. I’ve never met anyone from Wyoming before.

John Perry Barlow: Much less a Republican cattle rancher.

bell hooks: When we drop fear, we can draw nearer to people, we can draw nearer to the earth, we can draw nearer to all the heavenly creatures that surround us.

John Perry Barlow: I was just describing you to someone in terms of the externalities that would end up on your curriculum vitae, and the person said, she sounds like your polar opposite. On paper, you are my polar opposite and yet I feel none of that in your presence.

bell hooks: I actually feel that my heart was calling me to you. The first time we were in the same room for a prolonged period of time together, I sought you out. I wanted to hear your story.

John Perry Barlow: I felt the same way.

bell hooks: And what I see in a lot of young folks is this desire to be only with people like themselves and only to have any trust in reaching out to people like themselves. I think, what kind of magic are they going to miss in life? What kind of renewals of their beings will they never have, if they think you can have some computer printout that says this person has the same gender as you, the same race as you, the same class, and therefore they’re safe? I feel that intuition is so crucial to getting beyond race and class and gender, so that we can allow ourselves to feel for and with another person.

John Perry Barlow: I think that among the great errors of the political correctness movement is that it reduces things to their externalities and avoids the essence. I think that there is something about that whole academic, literary, critical culture that spawned a point of view that is anti-intimate.

bell hooks: Part of it is that, no matter how much that culture talks against it, it remains deeply rooted in mind-body-spirit.

John Perry Barlow: Underlying it is the belief that if you say the right words, if your language is appropriate, then your thoughts will necessarily follow, without seeing the great balancing act that goes on between any effort and that which resists it. On the West Coast now I find people to be in a lamentable condition. I honestly think that many of them feel that if they are careful about saying “African-American,” then they can be in complete denial about the fact that they are treating people like n****rs in their actions and in their unwillingness to open themselves emphatically to the people they encounter on the street. Here in New York, where people are liable to call one another anything, there is an empathic connection between the people on the street.

bell hooks: Partly there is this profound distrust of those things that can take us past race, past gender. I feel like it’s important to understand the meaning of those things, even as we are not held captive by them.

Information & Experience

John Perry Barlow: Much of what is critically ill in the American heart of the moment has to do with the confusion of information for experience, and reducing one’s map of the world to the informational. We are removed from all of the intuitive realities because we’re trying to experience them through this mediating and separating agency of television or the media in general. We’re living in highly desocialized conditions in our hermetically-sealed two-level ranch-style suburban homes.

bell hooks: I’ve been involved with a project called “Digital Diaspora,” and a lot of what people fear about computers is that they will simply intensify this privatization and alienation from body and spirit that you’re talking about. Do you see that?

John Perry Barlow: We’ve already been separated by information to an alarming extent. The difference between information and experience is that when you’re having an experience, you’re in real-time contact with the phenomena around you. You’re able to ask questions with every synapse in your body of the surrounding conditions. What I’m hopeful about is that because cyberspace is an interactive medium in a human sense, we’ll be able to go through this info-desert and be able to have something like tele-experience. We’ll be able to experience one other genuinely, in a truly interactive fashion, at a distance.

bell hooks: One of the things I think about is what it means to be communicating when you’re not aware of the specifics of who people are. You can’t respond to their looks, which are so central to the mechanisms of domination in our society. We judge on the basis of what somebody looks like, skin color, whether we think they’re beautiful or not. That space on the Internet allows you to converse with somebody with none of those things involved.

John Perry Barlow: There’s something problematic here, and I go back and forth on it all the time. I want to have a cyberspace that has prana in it. I want to have a cyberspace where there’s room for the breath and the spirit.

bell hooks: Well, that’s what I haven’t found, Barlow.

John Perry Barlow: Well, I haven’t either. The central question in my life at the moment is whether or not it’s possible to have it there. That’s what I’m really trying to figure out. Dialogue is not just language. The text itself is a minimal portion of the overall conversation. The overall conversation includes the color of your skin, and includes the way I smell, and includes the way we feel sitting here on the stoop with our thighs touching.

It’s not that there’s anything particularly healthy about cyberspace in itself, but the way in which cyberspace breaks down barriers. Cyberspace makes person-to-person interaction much more likely in an already fragmented society. The thing that people need desperately is random encounter. That’s what community has.

bell hooks: Seeing your computer, it feels like this lively possibility where anything may flash itself on that screen.

John Perry Barlow: There’s a big difference between the computer as a typewriter or a giant adding machine, and the computer as telephone or social space. I check my e-mail four or five times a day and I invariably get something utterly unexpected from a part of the world that I’ve never heard of before. That alerts me to the general human condition and makes me feel more connected to the entire species.

Garbage & Baggage

John Perry Barlow: I feel like I’m living in a metaphorical condition. I just spent the last hour and a half with an old poet who has spent his whole life in a metaphorical condition, and is about to be truly metaphorical. He said the most important thing was to take proper regard of the little things.

bell hooks: Part of what Buddhism has been for me is paying attention to the little things.

John Perry Barlow: Chop wood. Carry water.

bell hooks: I remember years ago when I first met Gary Snyder. I was really young; I didn’t understand that at all.

John Perry Barlow: Without a truly grounded context, words themselves don’t mean anything; metaphors don’t mean anything. A metaphor has to participate equally in the utterly physical and the truly spiritual. A metaphor is kind of a path between those two realms, and it’s a bad bridge that doesn’t have two ends.

bell hooks: Yesterday I was thinking about the whole idea of genius and creative people, and the notion that if you create some magical art, somehow that exempts you from having to pay attention to the small things.

John Perry Barlow: A big mistake, I suspect, but a mistake that I make all the time. I find that I make it more easily now that, in addition to being a smear on the geography because of my travels, my mind spends so much of its time in a completely disembodied state, inhabiting a social space where nobody has a body.

bell hooks: People have been telling me that as I become more of a little “star,” I should be hiring people to attend to the dailyness of my life. But I think I become something different when I don’t attend to the little things.

John Perry Barlow: I have a friend who used to take care of details for a senator from Wyoming. She said she would be happy to be my assistant on a part-time basis. I found myself resisting this, in spite of the fact that I am overwhelmed by things like calls to the travel agent and picking up the aspirin at the drug store, and all those utterly quotidian kinds of concerns.

A couple of years ago, I was coming into Narita Airport and found myself in the customs line behind Morita, the president of SONY, pushing all of his own baggage in a cart. Didn’t have some drone pushing his baggage for him. He was pushing his own baggage. And I thought, “There’s something. You’d never see an American captain of industry doing this, and there’s something about this that is essentially Buddhist.”

bell hooks: I feel that especially when it’s chores I don’t want to do, like taking out the garbage or doing my laundry. It’s in the act of having to do things that you don’t want to that you learn something about moving past the self. Past the ego.

Death & Dance

John Perry Barlow: I think an enlightened mind would be able to experience the vividness that novelty brings, even in things that are not novel. Thoreau said he’d travelled widely in the area around Walden Pond. The people who used to work on my ranch had never been outside of the state of Wyoming, but they had gone deeply into it. Whether we were fencing or minding cows, they could obviously perceive a deeper level of detail.

I keep thinking about the modern plague of boredom, which, ironically, is connected to the general social desire to make everything as familiar as possible, to turn everything into McDonald’s land or television land. And at the same time people are expressing a feeling of crushing ennui. I remember one of the few truly Buddhist things that my very non-Buddhist Wyoming mother said to me when I was little. I’d complain about being bored and she’d say, “Anyone who’s bored isn’t paying close enough attention.”

bell hooks: Whereas my mother in Kentucky always used to say, “Life is not promised,” in the sense that boredom is a luxury in this world. Where life is always fleeting, each moment has to be seized. For us children, that was a lesson in imagination, because she was always urging us to think of the imagination as that which allows you to crack through that space of ennui and get back going.

John Perry Barlow: That was what impressed me most about the old man that I went to see today. He is right on the edge of dying, and he knows that. He’s an intensely spiritual guy and every time I talked to him before, all he talked about was his memories of the spirit world from before he was born. Now I asked him if he could see through to the other side, and he said he didn’t want to think about the other side right now. It wasn’t a matter of denying it; it was wanting to put himself in the context of life as fully as possible. The moments are so precious to him now that he’s grabbing every one and savoring it.

bell hooks: I suppose I never think about death as an other side. Life is what’s on the other side; life is what we can’t get back to, because death is actually what we’re experiencing right now. Death is with you all the time; you get deeper in it as you move towards it, but it’s not unfamiliar to you. It’s always been there, so what becomes unfamiliar to you when you pass away from the moment is really life.

John Perry Barlow: You pass away from the moment into the infinite, where there are no moments and where there’s no time. Here in an embodied state, the body, like all physical things, participates in entropy and all the other artifacts of time. There’s a thin but nevertheless impermeable membrane between the chronological and the timeless that has become much more real to me since my lover died a year ago. Even though I feel her soul, the absence of her body feels like an enormous barrier. The absence of the spoken word, the absence of the sound of her voice, or the touch of her skin. All the things that only can be done by souls with bodies on them.

bell hooks: I wonder if those experiences are a call for us to feel the spirit more deeply. I think a lot about the phrase, “The sweet communion of the holy spirit,” because I think the holy spirit is part of what you found with your lover. And that’s part of what you can still have. When you talk about those tangible losses—the smell of another person, the sound of their voice, their movement—what resides, what stays in eternity, is that spirit that the two of you made between you.

John Perry Barlow: But you know the only time that I feel in contact with her, really, is when her spirit temporarily borrows someone else’s body to dance. Like the moment that you and I were dancing up in your apartment a few months ago. And suddenly she was in you and I could feel her there. You quit dancing the way you danced and started dancing the way she danced. And it was almost like a practical joke that she was playing in a way.

bell hooks: Well, that’s exactly why they call it spirit possession, because you’re taken over and you’re not yourself, but the other person has the moment of reunion.

Fear & Faith

John Perry Barlow: It’s only in the last year that I have been willing to accept on anything other than an intellectual level that the soul and the body are separable; that the spirit could go in and out of time and have new bodies.

bell hooks: Why did you have that resistance?

John Perry Barlow: Because I believed the dominant religion of this culture, which is science. And in science, only hypotheses whose results can be reproduced and observed are credible. Obviously when we talk about the spirit we have to talk about matters of faith, and when we talk about matters of faith, the lack of reproducibility is critical.

bell hooks: One of the guiding issues of my life right now is thinking about the difference between being fear-based and faith-based. When we think about the history of science, so much of it is rooted in this quest to find answers that will silence fear.

John Perry Barlow: And what has happened? We now have a society that is absolutely sick with fear. This is the most fearful place on the planet. It’s the place where science is dominant to the exclusion of all other religions. So it hasn’t been a very good answer so far. We take very little solace in our science.

bell hooks: What do you make of those people who are drawn to Buddhism because they see it as a more “scientific” religion than say, Islam or Christianity.

John Perry Barlow: And why would they say that?

bell hooks: I think because they see it as rational, reason based—the whole notion of cause and effect and of being able to even shift one’s consciousness through breathing. It’s more concrete in a lot of people’s imaginations, more rational.

John Perry Barlow: But a zen master would tell you, I think, that you’re not trying to shift consciousness through breathing; you’re trying to breathe and that’s all. Maybe this is an American misperception of Buddhism. We’re so causal that we take Buddhism and reculturate it in our own terms and inject a kind of causality that I don’t think the Buddha felt.

If you spend time among Buddhists, either in Japan or where I’ve been in northern India, in their own context, they don’t understand causality at all. I actually found myself years ago on top of a mountain with a Tibetan lama, just like a New Yorker cartoon. And he was asking me questions all the time about automobile mechanics. It was only afterwards that I realized that the reason he was so fascinated with automobile mechanics is that they’re so causal. You know, x causes y causes z. That was the source of his curiosity. I think that in the western cultures, we reinterpret Buddhism to be more causal than it is and we make it purposeful when,if you listen carefully, it seems that what they’re saying is that the purpose is its own purpose. The act is sufficient unto itself.

bell hooks: I think that’s why I’ve always been drawn to engaged Buddhism and to Thich Nhat Hanh, because there’s so much emphasis on the dailyness of life and doing what you do with a certain quality of mindfulness and stillness. You don’t have to have an agenda when you wake up in the morning, because waking up in the morning is what you’re doing.

John Perry Barlow: Lately I started to become concerned that in my frantic rushing around the world I was beating back stillness. But on closer examination, I feel like I am the eye of my own hurricane, and the more white noise I gather around myself, the more quiet it is in the center.

bell hooks: Well, I think about the difference between you and I often, because you’re such a guy for the road, and I’m such a girl for the living room. I really like to stay in my nest and not move. I travel in my mind, and that that’s a rigorous state of journeying for me. My body isn’t that interested in moving from place to place, and for me, stillness is always an experience of getting away from my mind. If I can get to sleep without my mind taking me on a journey, I feel happy.

Mothers & Forgiveness

bell hooks: For me the shift is away from the idea of love as a feeling to the sense of love as an action, love as something that I have to do rather than something that I could get by with just feeling. I had to be transformed in my actions towards others and the world. It really changed me.

John Perry Barlow: You don’t think that you were always like this?

bell hooks: No, like a lot of kids born into families where people didn’t understand them and tried to repress them, I think I was wounded in that space where I would know love. What saved me was that I had this incredible will to know, and the desire to know is central to the practice of love. If I didn’t want to know John Perry Barlow, if I hadn’t wanted to hear his story, we wouldn’t be on this stoop.

That desire to know kept me going and moving into love, despite the fact that as a child I felt sad all the time and there was a kind of competition between grief and love. Alice Miller says that for some children who are in a disturbed home environment, that is a place of magic as much as it can be a place of damage. Magic and damage don’t necessarily cancel out one another.

John Perry Barlow: Damage strengthens. I realized recently that I had a lot of reason to be grateful to my mother; my mother is a blame-based person.

bell hooks: Mine too. They must have known each other.

John Perry Barlow: She’s ninety years old and her mind is absolutely lucid. She can remember every time that anybody screwed up in her vicinity in the last ninety years. Her guiding belief is that shit is caused…by somebody. One of the things that I am most grateful for is that I’m about the most forgiving person I know. Or the most likely person to find extenuating circumstance in someone else’s behavior. She, more than anyone, taught me how to forgive by her own unwillingness to forgive.

bell hooks: It was seeking a path out of blame that led me to Buddhism. I was seeking a way out of that whole notion of wrong-doing, blame and punishment. I wanted something that actually had a promise that one would not have to inhabit the space of blame.

John Perry Barlow: But why didn’t you simply turn to your own religious tradition? Why didn’t you look at Christian absolution as being sufficient?

bell hooks: I’ve never given up on the mystical dimensions of Christianity. I always laugh at myself because in the morning I sit zazen, but then I always take time to say my Christian prayers at the same time. It’s like those two traditions have walked with me through my life and I haven’t been able to just choose one as the right one for me. I still feel like the sweetness of both of them enhances my life.

Journeys

John Perry Barlow: What I’ve decided is that thoughts and ideas and works of art and all of those apparently immaterial things are really life forms; they’re alive. And they have all of the characteristics of life forms. One of the things that you find if you’re doing animal husbandry is that there’s a lot of vigor in hybridization. If you really want something that has vigor and robustness, the best thing you can do is take two completely different gene sets and put them together. The space between things has energy in it, and I think part of what you and I have going for us is that there is some space between our externalities where the potential for informational life to grow up is highly fecant.

bell hooks: That’s the kind of border crossing that in cultural studies we call the hybridity of the future. The future is in moving out of the self into another space, not as a kind of tourism, but as a willingness to bring something to the other situation. This is involved with the whole tradition of gift-giving around the world. I think true hybridization is about your taking whatever you have to give and mingling it with whatever other folks have to give. One path that leads so many people to eastern thought is that longing to find a space where forgiving is sanctioned, and forgiveness can’t happen if you’re not allowed to believe in the power of giving. I think that the whole realm of capitalism is stifling in us the capacity to experience the gift, and the fundamental gift which we’ve been talking about is the gift of life, the breath.

John Perry Barlow: The problem with capitalism is that it’s based on physics and not biology. It’s based on entropy and not the fundamental reality of life, which creates new complexity and new order and higher states of energy all the time. Look how much value comes into the world out of absolutely nothing in the realm of information. The process of evolution is not one of entropy at all, but so much of the economy is about that extropic process. I think that one of the most helpful signs I see is a movement in economic theory toward the biological.

bell hooks: In journeying from place to place I’ve come to see how little I need to be alive in the world. There are days when I wake up and I feel overwhelmed by that sense of lust for goods and services, and I remind myself of people in the Kalahari desert and of how little it really takes to sustain ourselves.

John Perry Barlow: I travel with what I can easily carry down a jet concourse at high speed under my own power. And I never miss all those books and records and knick-knacks and things that fill my life whenever I’m stationary. I don’t find myself saying very often, “Oh, if only I were home then I would have this.”

bell hooks: But it’s precisely that kind of movement which is a movement into death and dying. A movement that says I’m really going to float free. I’m really going to be shedding each step of the way, so that when I come to that moment when I have to truly shed, I’m ready.

John Perry Barlow: I do feel, as I said in the beginning, like a physically metaphorical being. I feel like I’m an apparition even unto myself and certainly unto everybody who knows me. But at the same time, I feel much more vividly present in the moments that I share with people.

bell hooks: Which is, I think, the deepest way to accept death among us. That enables us to move into that greater clarity, that moment of knowing that this really is the moment. I love the Sutra of Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone where it says, “Life is in the present moment; to lose the present is to lose life.”

John Perry Barlow: Well, what else is there?